An Analysis of Institutional Racism and the Prison Industrial Complex in America

Abstract

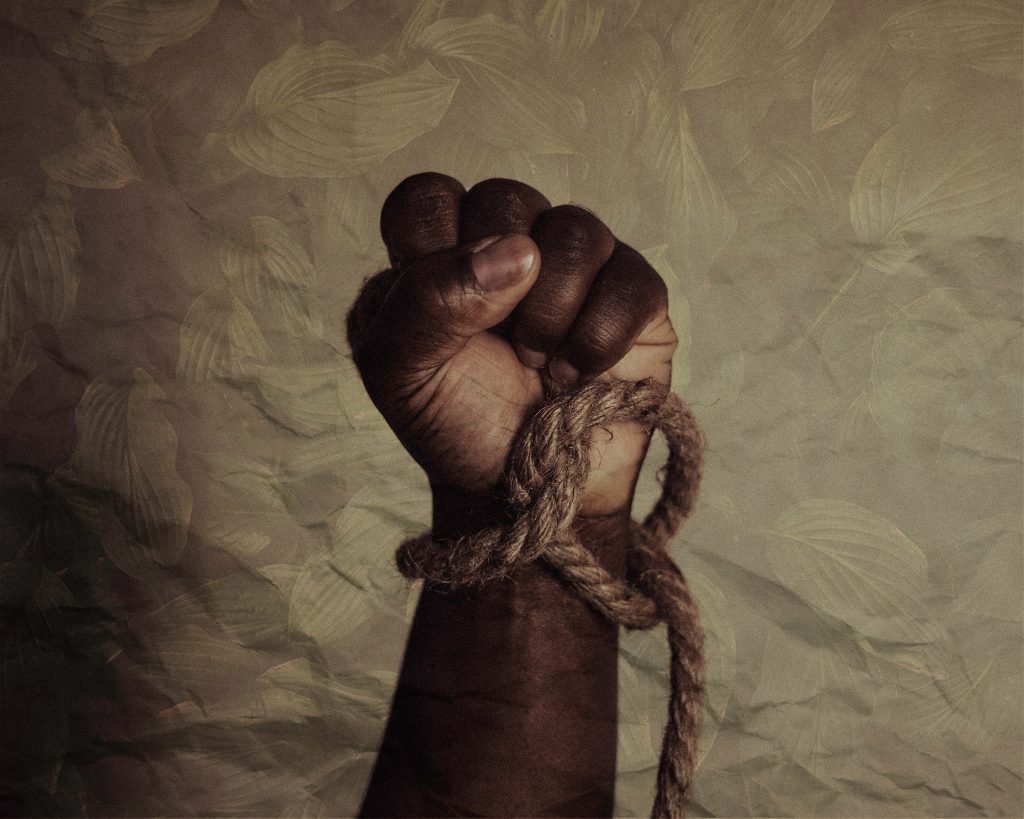

The United States of America was founded on the exploitation of African slaves’ labor, and that exploitation has continued far after their emancipation. Instead of plantations, the method of labor exploitation is the prison industrial complex. Private corporations work with the government to exploit prisoners’ vulnerable position in society, making them work long hours for low pay to maximize their profit. Despite politicians’ claims of America’s progressive nature relating to racial discrimination against black Americans, the country’s criminal justice institutions have not substantially changed in terms of their functioning on racial prejudices; they have just learned to mask them with racially coded language, shifting to a ‘colorblind’ presentation in which the legislation will target black Americans without explicitly saying so, but criminalize certain behaviors commonly associated with black communities. Understanding the historical background and evolution of systemic racism is crucial to grasping how firmly established it is within the modern institutions of America and why the mass incarceration of black Americans is generally accepted by the public. Today’s criminal justice institutions function on implicit racial biases, including law enforcement, prosecutors, criminal courts as well as landmark United States Supreme Court decisions that have upheld systemic racism. This has resulted in the drastic overcriminalization and overrepresentation in the prison population of black Americans. The legislation of the War on Crime and War on Drugs enacted after the 1964 Civil Rights Act permits the legalized discrimination against people with felony convictions which disproportionately affect black communities, including limiting their right to vote, access to government financial assistance and public housing, mirroring many of the policies that were supposedly repealed along with Jim Crow laws in the 1960s.

Author: Rachel McCurdy

BA (Hons) Criminology with Law, May 2021

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- A Brief History of Legal Segregation: From the Slave Codes to Jim Crow to 21st Century Resegregation

- Institutional Racism of the Criminal Justice System in Practice

- The Overcriminalization and Mass Incarceration of Black Communities and Effects of Disenfranchisement

- The Prison Industrial Complex: Modern Slavery

- Conclusion

- References

1. Introduction

Systemic racism against black Americans has been ingrained in the social and legal framework of the United States since the country’s inception. The modern political, economic and criminal justice institutions have evolved from those functioning during slavery in the 17th to 19th centuries and the subsequent Black Codes and Jim Crow laws to their current form. From local police departments all the way up to the federal government (Banks, 2016), the effects of historic institutional racism are heavily felt by black Americans and their communities today. Each individual institution within the American criminal justice system plays a role in the continuance of systemic racism against black Americans, and their combination, since the 1960s, has resulted in the mass incarceration of black Americans at rates far higher than any point in history (Garland, 2001: 9). Law enforcement officers have historically targeted black communities in their policing, dating back to their origins as the slave patrols before the abolition of slavery (Hassett-Walker, 2020) and their following evolution into a force focusing on policing freed black Americans under the Black Codes (Nittle, 2021). Today, racially discriminate policing takes the form of making arrests and using excessive force more frequently (Christopher Commission, 1991: 6) in black neighborhoods, often based on implicit biases of those areas and the people living in them. Black Americans’ overrepresentation in arrests and violent police interactions marks the beginning of the process of their overrepresentation throughout the entire criminal justice system; prosecutors and criminal court judges are also likely to act on implicit racial biases, resulting in more black defendants receiving harsher charges, sentences and less beneficial plea deals when compared with white defendants (Sawyer, 2019). Black Americans are therefore severely overrepresented in the prison population, constituting 13% of the general United States population but 38% of the prison population as of 2016 (Nellis, 2016).

Just as the institutions of law enforcement and criminal courts have evolved from their predecessors of the slavery, Black Codes and Jim Crow eras, the prison system has evolved to become the modern plantation. The prison industrial complex arose from the period of mass incarceration of black Americans in the later decades of the 1900s, involving private businesses merging with the government to run and own their own prisons, often being able to bypass the regulations that government-run prisons are bound to (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 349). These private institutions require inmates to work in order to pay for their own incarceration, much like the previous practice of convict leasing used in the period after slavery’s abolition, with significant portions of their wages deducted and given directly to the prison.

Modern institutional racism is able to function under the guise of criminal justice, successfully criminalizing black Americans in the eyes of the public through ‘colorblind’ racially coded legislation and political rhetoric. The shift from overt institutional racism to colorblind racism occurred after the repeal of Jim Crow laws with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and involves legislation that does not explicitly discriminate against black Americans, but targets them through other means and provides a defense for policymakers to say that any racial disparities in the effects of the legislation are just naturally occurring (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 626). The racial disparities in the prison population grew exponentially during the period from the end of the Civil Rights Movement through the 1990s, largely due to the colorblind legislation enacted at this time. The contemporary debate among many Americans is whether institutional racism exists, but a more productive conversation would be discussing how we have allowed it to persist through multiple generations.

2. A Brief History of Legal Segregation: From the Slave Codes to Jim Crow to 21st Century Resegregation

The Origins of Law Enforcement in the Slave Patrols

The history of the modern day legal institutions and law enforcement practices are rooted primarily within the ‘slave patrols’ used in southern slave states, and the discriminatory systems of laws that followed. The slave patrols consisted of white volunteers who used vigilantism to catch and return escaped slaves, put an end to slave uprisings, and punishenslaved people accused of violating plantation rules (Hassett-Walker, 2020), a system of laws referred to as the ‘slave codes’. The patrols’ most pressing issue was that of slave uprisings, because they were seen as a “threat to the social order” (Hasset-Walker, 2021) of American life. These forces were first established in the early 1700s in South Carolina, then quickly spread to all states that practiced slavery. Slave codes were abolished along with the practice of slavery after the Civil War, but were swiftly replaced with the ‘Black Codes’. The slave patrols simply evolved into southern states’ police departments (Hassett-Walker, 2021), similar in appearance and function to the ones in northern non-slave states, but the members remained the same. The ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 required all former slave state governments to recognize and comply with abolition, but gave them all other freedoms to rebuild their governments how they saw fit (Nittle, 2021). Because their economies were so heavily dependent on slave labor, the legislatures and ruling classes of southern states, composed of white men, shortly thereafter created the Black Codes to dictate when, where and how black Americans could be employed, how much they were able to earn, restricted their voting rights and limited where they could live and travel (Hassett-Walker, 2020).

The Evolution of the Slave Codes into the Black Codes

The first of the Black Codes were enacted in 1865 in Mississippi and South Carolina, limiting black people to working only as farmers or servants and requiring them to sign yearly employment contracts to ensure that they earn the lowest wage legally permissible, otherwise risking arrest and losing all of their earned wages (Nittle, 2021). They also included statutes for punishing white employers for offering higher wages to black workers than their contracts permitted, as well as apprenticeship laws forcing black minors into unpaid labor for white plantation owners if they were orphans or their parents were ruled by a judge to be unfit to care for them (Nittle, 2021). Nearly all southern states followed suit and enacted their own Black Codes, extending the scope of this new system of slavery: contracted labor with very limited freedoms for black workers. Because they earned such low wages, imposing fees on black Americans was another effective way for the government to re-enslave them; the practice of debt peonage was widespread, involving the forced unpaid labor of black people who were indebted to employers, businesses, or the court system in order to pay off the fees (Nittle, 2021), often with high interest rates to keep their debt prolonged. Therefore, these laws were enacted not only to restrict the freedoms of former slaves, but also to solidify their status as a source of cheap labor. Convict leasing also became commonplace, a type of forced labor involving sending inmates to work directly for private businesses, often in identical conditions to slavery. A loophole within the Thirteenth Amendment made these practices possible; the language of this Amendment prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude in all circumstances ‘except as punishment for crime’ (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 359), which all but gives states permission to enslave their prisoners. Southern states took advantage of this by criminalizing common behaviors that would make it easier to imprison black Americans, and provide a justification for their forced labor. Overcriminalized behaviors include loitering and vagrancy (Nittle, 2021), which were intentionally given vague definitions in order to ensure a wide scope of applicability. The only choices available to black Americans were to enter an exploitative employment contract or be arrested for vagrancy for being unemployed, which would place them in either debt peonage or convict leasing once in prison. This practice also aided that of debt peonage, because the state then had an increasing population of incarcerated black Americans who could not pay their legal fees. Local business owners would pay their fees in exchange for free labor until the debt was paid (Wagner, 2012), again trapping them in the indebted labor cycle. These abuses of the criminal justice system to disproportionately target black Americans and force them into debt peonage or convict leasing, and the failures of the federal courts and government to adequately address them, has created the opportunity for these practices to evolve into the modern prison industrial complex, which will be detailed in a later chapter.

The Introduction of Jim Crow Laws

The Black Codes were enforced by an all-white police force, many of whom were former Confederate soldiers (Nittle, 2021) and members of the slave patrols. These laws were made illegal through the passing of the 1867 Reconstruction Act, and the ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments in the late 1860s, a result of the Reconstruction Act, guaranteed black Americans equal protections under the Constitution and extended voting rights to all men, regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (Nittle, 2021). Black men were subsequently elected to positions of authority from local government offices up to the United States Congress. Despite these new legal protections and apparent steps towards equality, white southerners were still committed to asserting their dominance and undermined this progress through the rising violence and prominence of the white supremacy group, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Along with the legal loophole states found within the Thirteenth Amendment to justify the forced unpaid labor of prisoners, they also found one for the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted black citizens the right to vote. Many states began requiring ‘poll taxes’ to be paid and a literacy test to be passed (Hassett-Walker, 2021), which they knew most black citizens would not be able to do while whites could. In the years following the Reconstruction Act, Black Codes were replaced by Jim Crow laws, but most of the practices remained the same, including debt peonage and employment contracts ensuring lower pay for black workers.

The name ‘Jim Crow’ originated from a character in a minstrel show involving a white actor performing a skit of racist stereotypes of black people, wearing dramatic black paint over his face (Mullen et. al, 2021). The title of these laws, along with the Black Codes, communicated to black Americans that these regulations were meant for them and only them, confirming their position as second-class citizens. Both sets of laws had the same intent of limiting black Americans’ civil rights; Jim Crow laws executed this through segregating the public spaces of blacks and whites, including separate schools, libraries, water fountains, bathrooms and restaurants (Hassett-Walker, 2020). The states imposing Jim Crow laws said they provided ‘separate but equal’ facilities (Nittle, 2021), but this was very clearly not the case; black communities were severely underfunded and violently harassed by the KKK consistently. State politicians argued that segregation of the races was to ‘preserve law and order’ (Banks, 2016). This rhetoric further pushed the overcriminalization of black people, assuming that if the races were not segregated, crime rates would rise and whites would be at risk of victimization from black men. Although black Americans appeared to have more legal freedoms than in the days of slavery, southern state governments were able to get away with infringing on their rights for decades under the guise of the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine.

The Shift of Law Enforcement’s Role

For the 80 years Jim Crow laws were in effect, it was the job of police officers to enforce them and punish black Americans who broke them. The same police force, prosecutors and judges went from enforcing the Black Codes and prosecuting perceived violators of them to enforcing Jim Crow laws. Law enforcement’s purpose during the Jim Crow era evolved to maintaining the status quo; instead of slave uprisings on plantations, they were charged with controlling civil rights protests. Protesters were often met with excessive violence from the police, including attacks from police dogs, riot gear and tear gas (Hassett-Walker, 2021). Those found to be in violation of segregation laws were also commonly subjected to extreme force from police. In contrast, the police never arrested or prosecuted white supremacist mobs when they targeted, attacked and lynched blacks (Hassett-Walker, 2020). Lynchings became frequent, usually used to send a message to a black community (Hassett-Walker, 2020) and could result from virtually any behavior that whites perceived as out of line (Nittle, 2021). From the mid-1800s to early 1900s, there were over 3000 lynchings, commonly with police officers in attendance who did not intervene (Banks, 2016: 100). The increase in unpunished, and even glorified, lynchings in the years after World War I was found to embolden the mob mentality of white men and vigilante anti-black groups like the KKK (Stevenson, 2017: 23). The lynchings also contributed to furthering the widespread belief that black people were inherently criminal, because someone could accuse a black person of any crime, and without evidence a white mob would beat and torture them until they confessed (Stevenson, 2017: 30). These confessions, often false and only made because of the pain the victim was in, then provided somewhat of a justification for the attackers’ violent actions. Law enforcement, instead of investigating whether the black victim was actually guilty of the accused crime, would take the confessions as fact, assume they were guilty and move on. After a particularly violent lynching in Florida in 1919, the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) approached the state’s governor pleading him to take action and prosecute those involved. He refused to press charges against the lynchers, because “the citizenship will not stand for it” (Stevenson, 2017: 30), putting the prejudiced views of white Americans over the safety and wellbeing of black Americans.

The Modern Evolution of Institutional Racism

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 made segregation and employment discrimination based on race illegal, repealing Jim Crow laws. The Voting Rights Act followed shortly after in 1965, aiming to reverse the legal loopholes used by states to restrict black Americans’ right to vote. However, instead of enacting proactive legislation to try and reverse the effects of the Black Codes or Jim Crow laws, the federal and state governments simply adapted to continue their practices without technically breaking the law. For example, more black men are incarcerated today than were enslaved in 1850 and similarly to the Jim Crow era, are mainly convicted for offenses that are overwhelmingly ignored when committed by whites (Alexander, 2012: 180), particularly drug offenses. The overcriminalization of black communities and mass incarceration of black men has been an ongoing practice since they were freed as slaves, and while the technicalities of prison labor have changed, it is still commonly used as well. The police tactics of excessive violence on black people have not changed substantially either, especially in instances of protests and civil unrest (Hassett-Walker, 2021). The role of law enforcement has shifted according to the laws of the time, from its origins in the slave patrols to Jim Crow laws to modern day.

The discriminatory practices permitted by the slave codes, Black Codes, and Jim Crow laws laid the foundation for the modern institutions of the United States. We have witnessed a trend of law enforcement and states’ laws adapting to the current standard of federal law, but just enough to mask their practices of exploiting black Americans. When slavery was abolished, the slave patrols became police departments and slave codes became Black Codes, continuing the practice of forced labor through mass incarceration and indebting of black people. Following the outlawing of the Black Codes, Jim Crow laws replaced them and continued the criminalization and mass incarceration of black Americans by creating arbitrary laws specifically to trap them into ‘committing a crime’, such as using an elevator exclusively for whites (Mullen et. al, 2021) as an excuse to imprison them and sentence them to work without pay. Given this trend, it is not unreasonable for one to conclude that after the Civil Rights Movement and prohibition of Jim Crow laws in the 1960s, the American institutions of today have simply adapted again to meet the federal legal standards.

3. Institutional Racism of the Criminal Justice System in Practice

The effects of institutional racism, as have been established to be deeply rooted in the foundations of American society, are heavily felt in the modern criminal justice system in all processes, from policing and arrests to prosecution and sentencing. One component of institutional racism is ‘petit apartheid’, which includes the daily informal and unreported actions between police and black people through procedures like traffic stops or routine searches and questionings (Banks, 2016). This concept centers its focus on the attitudes of actors within the criminal justice system that affect their enforcement of the law and can be expressed through verbal and physical abuse from police, lack of civil treatment of black suspects, more serious charges given to black defendants, offering bail conditions to black defendants at lower rates than white defendants (Banks, 2016) and other discretionary practices of the system. The high levels of discretion given to actors within the criminal justice system, from police officers to prosecutors to criminal court judges, allow for racial profiling to run rampant through the entire process and prevent black Americans from receiving the fair treatment they are entitled to under the Constitution.

The Effect of Police Culture on Discriminatory Policing

There is a culture within the police leading them to act on implicit biases towards racial minorities, especially black people. All occupations have their own subcultures based on the members’ shared experiences, and police subculture has been defined as the “accepted practices, rules and principles of conduct that are situationally applied, and generalized rationales and beliefs” (Banks, 2016). This culture creates an ‘us versus them’ mentality among officers (Brooks, 2020), leading them to disconnect from the members of the public they are supposed to protect. Most new recruits join the police force as “an opportunity to help people in the community” (Brooks, 2020), but the organizational culture often alters their perceptions, beginning during the training process. Trainees are sent into an environment similar to military boot camp, beginning the disconnect from their communities. During training, police recruits are told all of the worst possible scenarios that they should be prepared for, and are told hypothetical scenarios that ‘…a guy with a knife 21 feet away can run up and stab you before you have the chance to draw your gun’ (Brooks, 2020). These exaggerated scenarios, on top of watching body camera videos and listening to radio recordings of officers who have died in the line of duty, set the recruits up with a mindset that people in the community are out to get them and they need to defend themselves. When they enter the police force, the new officers are on edge and often make quick judgments based on what they have learned in their environment and commonly held racial stereotypes ingrained in the social framework of America. The most prevalent value taught through the police subculture is the ability to judge the nature of the suspect when enforcing the law, using factors such as their demeanor, degree of cooperation with officers, race, age and social class (Banks, 2016). Godsil and Jiang (2018) conducted a study of subliminal exposure through words or images with employees of the criminal justice system, including police officers, to gauge how implicit racial bias affects their decision making. When participants were presented with common black American names, rap or hip-hop music or descriptions of black neighborhoods, their racial biases were stimulated and affected the outcome of their hypothetical decision through choosing harsher charges or sentences for these cases, sometimes without their knowledge (Godsil and Jiang, 2018: 147). These implicit biases stem from the longstanding stereotype that black people, particularly black men, are more likely to commit crime and commonly results in racial profiling in arrests, traffic stops or stop-and-frisk practices and acts of brutality that disproportionately occur in black neighborhoods.

The police practices of investigatory traffic stops and stop-and-frisk procedures make up the majority of racial disparities in police interactions and arrests because of the high levels of discretion given to officers in stopping suspects. Black people are more likely than any other race to experience investigatory stops, which are defined as “a police stop where the intent is not to sanction a driving violation but to look for evidence of a more serious criminal offense” (Banks, 2016). Officers will identify minor traffic offenses such as a broken tail light as a reason to stop drivers and search their cars for drugs or other illegal items without a warrant or probable cause, a practice that was created with the intention of being proactive and reducing crime. A study from Stanford University conducted from 2011-2017 analyzed 100 million routine traffic stops and found that black drivers were more likely not only to be pulled over, but also have their car searched by police (Banks, 2016). An analysis of traffic stops in Washington D.C. corroborated this result, finding that black people made up 46% of the city’s population, but 70% of traffic stops and 86% of investigatory stops unrelated to traffic violations (Balko, 2020). Although black drivers had their cars searched at a disproportionately high rate, it was found that white drivers were more likely to actually be found with drugs or other illegal contraband. This study also found that the percentage of black drivers pulled over decreased at night, when it was too dark for officers to see the details of the driver (Hasset-Walker, 2020). Research from across the United States from Los Angeles to Washington D.C. has yielded the same results (Bartelme and Smith, 2015); black drivers are subjected to investigatory stops at far higher rates than white drivers, despite their low percentage of the overall population. This displays the widespread nature of police institutional culture and racial biases, and when combined with a discretionary procedure involving making judgments based on someone’s physical appearance, officers are heavily inclined to believe that black people are inherently more suspect than whites. Given the systemic scale of racial discrimination in investigatory stops and general policing, black Americans nationwide often have a shared tension with law enforcment, with some of their interactions resulting in excessive force from police.

While this is not a novel concept and police have been historically known to use physical violence against black Americans since the creation of police forces, the issue was thrust into the public eye after the 1991 beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles, and subsequent acquittal of the four officers involved. A witness to the event took a video, which was shown on news stations nationwide (Sastry and Bates, 2017); the jury’s decision to find the officers not guilty on the charges of excessive use of force in spite of video evidence shocked the country. The graphic video displayed the aftermath of a car chase in which Rodney King was trying to outrun the police before eventually giving up, and instead of simply arresting him, the four officers kicked him and beat him with batons for 15 minutes with over 12 other officers standing by watching (Sastry and Bates, 2017). The Christopher Commission, formed by the Los Angeles mayor in 1991 after the Rodney King incident, published a report analyzing the department’s incidents of officers using excessive force. According to the report (1991), the race of the suspect commonly plays a role in officers’ use of brutality, and there is a trend of increased aggression when policing predominantly black neighborhoods. Just under half of the officers who responded to the Commission’s survey for the report said that racial bias is indeed a factor leading to the use of excessive force. The Commission’s report displayed transcribed radio communications between officers containing derogatory statements about black people, including “[It] sounds like monkey slapping time…” (Christopher Commission, 1991: 6) in reference to patrolling a black neighborhood. The radio messages taken from police patrol cars conveyed officers’ enjoyment of the excitement of chasing a suspect, even seeing it as an opportunity for using excessive force, with one officer saying “…capture him, beat him and treat him like dirt…” (Christopher Commission, 1991: 5). Even more alarming than the contents of these statements is the confidence of the officers making them; they display no regard for potential repercussions for these racist or violent statements because they know they will be protected by the police force. The Christopher Commission addressed the lack of accountability for officers making clearly racially biased statements and using excessive force, finding through interviews with present and former LAPD officers that “a significant number of officers tended to use force excessively, that these problem officers were well known in their divisions, that the Department’s efforts to control or discipline those officers were inadequate…” (Christopher Commission, 1991: 3). It was found that between the years of 1987 to 1991, one LAPD officer had 13 allegations of excessive force, 5 other formal complaints, 28 use of force reports and 1 shooting, but had performance evaluations that were overwhelmingly positive (Christopher Commission, 1991: 4). On the opposite side of the country in Charleston, North Carolina, a white police officer fatally shot a black man named Walter Scott in 2015 after an investigatory traffic stop. Upon the investigation following the incident, it was found that this officer had three previous use of force complaints filed against him, all of which were dismissed by his superiors (Bartelme and Smith, 2015). This proves another aspect of systemic discrimination within the institution of the police in addition to that of racial profiling; the level of loyalty that law enforcement has, and the lengths that superior members will go to in order to protect their reputation. The sense of loyalty created by the organizational culture within the police force results in an environment where “reporting excessive force or the use of racial slurs by a colleague is an act of treason” (Beauchamp, 2020).

The United States Supreme Court’s Role in Upholding Institutional Racism in Criminal Justice

Although law enforcement is a powerful organization capable of concealing incidents of abuse, they cannot do it alone. The entire criminal justice system including the high courts, prosecutors and judges all have a hand in allowing police officers to avoid consequences for their abuses of power and excessive uses of force. The discretionary powers of the police allowing for more opportunity of racial profiling were established in the 1968 United States Supreme Court (USSC) case of Terry v. Ohio (Banks, 2016), and have been upheld in cases ever since. The legality of investigatory stops was challenged in the USSC case Whren v. United States in 1996, with the appellant alleging that his Fourth Amendment right to protection from unlawful searches was violated by the officers because they searched him without reason. The Court ruled that the practice does not violate citizens’ rights under the Fourth Amendment because the stop was executed based on an objective violation of the law, which in this case was the appellant not using his turn signal (Banks, 2016). The Court cited their decision in the 1987 case McCleskey v. Kemp, saying that ‘purposeful discrimination’ must be proven in the case in order for the stop, search or arrest to be considered unlawful under the Constitution (Banks, 2016). The Court has given police further discretionary powers in their functions regarding their uses of force, beginning with the lack of formal definition for what constitutes ‘excessive force’. In the 1989 case Graham v. Connor, the Court held that an officer’s use of force must be judged based on ‘objective reasonableness’ from the perspective of the officers on the scene (Lhamon et al, 2018: 10), allowing for maximum discretion of police departments to justify that their actions, however extreme, were necessary in the circumstances. It has also created a system that prioritizes police officers over minority communities who have been victimized by their discrimination or physical abuses, because with the discretion of whether or not the force was justified primarily in the hands of the police departments, the officers and their superiors will certainly defend each other and use the USSC’s rulings to their advantage.

The Role of Prosecutors and Judges’ Discretionary Power in Institutional Racism Against Black Americans

The role of prosecutors in upholding institutional racism in the criminal justice system coincides with that of the police. Chief prosecutors in most jurisdictions are elected to their position, so their decisions of whether or not to file charges against someone are inherently political in nature and made with both the intention of pleasing potential voters and achieving justice. When a case arises where a police officer has injured or killed a member of the public while on duty, prosecutors face a dilemma between the two intentions because they need the support of police departments to do their job effectively, and the majority of the voting population generally respect the police (Hegarty, 2017: 306). Charging and prosecuting an officer for an excessive use of force, assault or murder may result in significant political backlash on the chief prosecutor, and there is consequently a lack of indictments against officers in relation to the amount of unarmed people killed by them (Hegarty, 2017: 306).

Prosecutors and criminal court judges’ discretionary power also plays a role in other aspects of upholding institutional racism in the criminal justice system. The levels of racial disparity in the United States prison population raises concern; black Americans make up 13% of the overall population, but 35% of the prison population as of 2014 (Banks, 2016). This suggests that in addition to being disproportionately searched and arrested by police, black people are more likely to be prosecuted and sentenced to prison time than whites as well. An analysis of over 30,000 criminal cases in Los Angeles revealed that black defendants were prosecuted at a far higher rate than white ones (Banks, 2016). Berdejo’s study (2017) of 48,000 criminal cases in Wisconsin supported this result, and additionally found that white defendants were 75% more likely to be offered a plea deal by prosecutors dismissing their most serious charge and avoiding prison time altogether. Even when black and white defendants were charged with similar offenses and had comparable prior records, whites were still significantly more likely to have their charges reduced (Berdejo, 2017). Criminal court judges also have discretion when deciding whether to release a defendant on bail or determining the appropriate sentences, and often base their decisions on factors such as the defendant’s danger to the public or likelihood of fleeing, but also look at personal details like their marital status, prior criminal records, employment history and length of residence in the area (Banks, 2016). A 1989 study of 5,000 male defendants showed that those with lower education and income levels were less likely to be granted bail or be offered a bail amount that is clearly unattainable for them, but whites with the same level of education and income as blacks were still offered reasonable bail at higher rates (Banks, 2016). In addition to being arrested, prosecuted and denied bail at higher rates, black Americans are more likely to receive much longer sentences than whites even when charged with the same crimes; the United States Sentencing Commission analyzed 34,000 criminal cases from around the country and found that young black males receive the harshest sentences, at 42% longer than young white males charged with similar offenses (Banks, 2016). Black Americans have been historically more likely to receive the death penalty than whites, dating back to lynchings commonly occurring in the Jim Crow era after simply being accused of a crime. Today, they are still more likely to receive the death penalty than white defendants, especially if the victim is a white woman (Banks, 2016). Conversely, murder cases involving black victims are less likely to result in the death penalty or be seen by juries as particularly tragic, especially when the perpetrator is white, a phenomenon commonly referred to as the ‘black victim effect’ (Banks, 2016). The disproportionate amount of black Americans prosecuted and sentenced to prison compared to other races suggests that prosecutors and judges, like police officers, also act on their personally-held racial biases when using discretion in decision-making. Similar to the complications with police officers being held accountable for racial discrimination, proof of intentional discrimination by prosecutors or judges (Banks, 2016) must be proven in order for a conviction or sentence to be challenged on those grounds. It is nearly impossible to prove that actors within the criminal justice system have made decisions deliberately based on racial stereotypes, so black people are therefore overrepresented in arrests, convictions, and the prison population with few avenues to challenge the injustice within the criminal justice system. This continues the cycle of perpetuating the widespread stereotype that black people are more prone to criminal activity, because actors within the criminal justice system act on this implicit bias, leading to overrepresentation of black Americans in the system, thus creating somewhat of a justification to be used by these actors for the stigmatization and overcriminalization of black communities.

4. The Overcriminalization and Mass Incarceration of Black Communities and Effects of Disenfranchisement

The Modern Evolution of Institutional Racism: Colorblind Racism

As seen through the previous chapter detailing the discretionary processes of law enforcement, criminal courts, legislators and the Supreme Court, institutional racism in the modern criminal justice system has manifested itself through more indirect means, namely the implicit biases within the framework of the system. We have witnessed a shift from the old ways of explicit racism in the United States’ government institutions to one claiming to be ‘colorblind’ in its creation and application of the law. This claim of colorblindness in the eyes of the law and those enforcing it provides lawmakers with the argument that because race is not explicitly mentioned in legislation, it is therefore an irrelevant factor when discussing the potential negative consequences of the legislation (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 626). These consequences include the political, social and economic ‘invisible punishments’ (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 627) experienced heavily by black communities nationwide due to their overrepresentation in the prison population, which will be further expanded upon in this chapter. Colorblind racism attributes mass incarceration of black people to their disproportionately high involvement in crime, disregarding any possibility of discrimination within the system and argues that systemic racism was extinguished with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 629). The criminal legislation enacted by the federal government during the ‘War on Crime’ and ‘War on Drugs’ eras from the 1960s to 1990s predominantly criminalized black neighborhoods, but because the laws did not mention race specifically in their phrasing, lawmakers and criminal justice officials denied any racial bias. These policies were masked as a crime control measure to prioritize public safety, but in reality were weaponized against black Americans (American Sociological Association, 2007: 5), essentially becoming the modern, more discreet Jim Crow. The effects of the mass incarceration caused by this legislation are still widely felt by black communities across the United States, typically in the forms of extreme poverty, lack of education or employment opportunities and voter disenfranchisement, but legislators still deny that they stem from racial bias within the criminal justice system. The election of Barack Obama in 2008 was described by politicians and political commentators as marking the ‘post-racial era’ in America, supporting the colorblind negation of the existence of institutionalized racism (Smiley and Fakunle, 2016); Fox News host Laura Ingraham shut down President Joe Biden’s claim of systemic racism in America, saying it was “[a] big lie…Did he believe this when he and Barack Obama were elected not once but twice?” (Moran, 2021). The USSC decision in the 1987 case McCleskey v. Kemp provides a legal basis supporting this view, defining discrimination as an individual, not institutionalized problem (Banks, 2016). In addition to this decision’s impact of protecting acts of racial discrimination by requiring intentional discrimination to be proven, it aided in the normalization of racial disparities in the prison population and elsewhere in the system, allowing them to continue without question.

The Beginning of the Mass Imprisonment of Black Americans: The War on Crime and War on Drugs

David Garland (2001) coined the term ‘mass imprisonment’ in reference to the explosive increase in the prison system and population in the United States since the 1970s, largely due to the ‘crime control’ policies of the War on Crime and War on Drugs eras. The American culture of individualism rather than collectivism is referenced by criminologists as a factor in the public acceptance of harsh penal policies and the rise of mass imprisonment of black Americans (Garland, 2001: 9), especially in the age of colorblind politics; we are encouraged to overlook the societal root causes of crime and accept that some individuals are prone to violence and unable to be rehabilitated, so they deserve to be segregated from society. The early decades of the 1900s saw over 6 million black Americans migrate from southern former slave states to urban northern cities to escape the discrimination of severe Jim Crow laws (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 271), creating a moral panic among whites in those cities to fear the perceived ‘threat’ of unemployed, impoverished black men and youth. The spike in mass incarceration, mainly affecting black neighborhoods in urban areas, was explained by politicians and media as a response to the rising crime rate in those areas through their fear-mongering and sensationalized news coverage (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 271), a narrative widely accepted by the general public because of their growing fear of black neighborhoods. The fears of white America became the focus of criminal justice policy, marking the shift towards normalizing the mass incarceration of black Americans. Before President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Crime policies and rhetoric, the public largely viewed crime as a problem of poor urban communities that stemmed from their deprivation of educational or job opportunities and proper treatment for psychological conditions that deserved aid and rehabilitation (Garland, 2002: 15). Between these new crime control policies and sensationalized media reports, crime came to be seen as perpetrated by dangerous, career criminals that were unable to be rehabilitated, regardless of their socioeconomic standing. The term ‘thug’ has been used in media reports depicting black people from the Civil Rights Movement to today, commonly in relation to civil rights or anti-police brutality protests. People watch the news expecting a reliable source to inform them of current events, so it is not surprising to see the media’s role in perpetuating the stereotype of black people’s inherent criminality to the public. Referring to black communities as ‘ghetto’ or ‘the hood’ and the people living in them as ‘thugs’ creates a system of racially-coded language in the modern era of colorblindness, upholding antiblack prejudices without overtly expressing them (Smiley and Fakunle, 2016). This coded language continues to be used in the news media today, with Fox News host Tucker Carlson calling Black Lives Matter protestors “…antisocial thugs with no stake in society” (Owen, 2020), in reference to the widespread protests against police brutality and excessive force in the summer of 2020.

Following the civil rights protests and uprisings beginning in the summer of 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a ‘War on Crime’ in 1965. His administration gave major financial investments from the federal government to police departments all over the country, with particularly large amounts to urban areas. Their aim was to ‘prevent future disorder’ (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 272), but the later half of the 1960s saw even more civil unrest, mostly stemming from incidents of police brutality. Public officials labeled this as “evidence of criminality” (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 272) of urban black communities that warranted harsher force. Directly associating civil rights protests against police brutality with crime serves to confirm the longstanding racial stereotypes of black Americans’ criminal nature, and provides a platform for law enforcement and governments to continue enacting policies that disparately target them. This criminalization of protest, an action listed as a right for all Americans in the First Amendment, follows the trend of the Black Codes and Jim Crow eras in which the state and federal governments criminalized common behaviors of black communities, stigmatizing them and keeping them in constant contact with the criminal justice system. The Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 marked a pivotal moment in America’s trend of controlling black communities through the criminal justice system. The Act allocated a further $300 million to the War on Crime to increase policing in low-income urban neighborhoods, providing officers with military-grade weapons and new surveillance technologies (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 272). The wording of ‘low-income urban neighborhoods’ was intentional, because the government knew that these areas were predominantly populated by black Americans, creating an opportunity to effectively target them through policing without explicitly racially profiling. This led to the sharp increase of black Americans represented in the prison population, rising from 27.4% to 38% from 1970 to 1977 (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 273) and a higher rate of black people’s imprisonment in any other society historically, including the apartheid period in South Africa (Garland, 2001: 82). In addition to increased police resources, the 1968 Act decreased funding to education, employment and training programs in these low-income urban neighborhoods (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 273), limiting black Americans’ opportunities to support their families and increasing the chances of their incarceration. The decreased resources given to urban black communities served to create an environment referred to as the ‘hyperghetto’ (Garland, 2001: 91), enhancing the modern segregation of cities versus suburbs through trapping black Americans in impoverished areas with little opportunity to relocate or advance their socioeconomic positions. This environment welcoming of the modern form of punitive segregation (Garland, 2002: 200) was only further solidified during the War on Drugs decades, in which even harsher, more racially disparate policing and sentencing legislation was passed.

President Johnson’s War on Crime heavily inspired President Ronald Reagan’s proclaimed ‘War on Drugs’ in the 1980s, beginning with his passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1986. The Reagan administration gave police departments in the same urban cities even more funding, military-grade equipment and surveillance technology, in addition to increased police powers for preventive patrols (Hinton and Cook, 2020: 274). Urban black neighborhoods were already feeling the effects of discriminatory over-policing, and were now subject to more discretionary policing measures of unwarranted searches that almost ensured their contact with the criminal justice system. The differences in criminal penalties used for drug offenses further exacerbated the racial disparities in the prison population, some of which are still in effect today. Crack cocaine, which is predominantly used and sold in inner city black neighborhoods, carried a mandatory sentence of five years in prison for possession of five grams (American Sociological Association, 2007: 6). Conversely, the same law prescribed the same five year sentence for possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine, which is commonly used in middle to upper class white neighborhoods. Reagan’s administration argued that the differences in sentencing were due to crack cocaine being more addictive and harmful, but pharmacology studies have proven that to be false (American Sociological Association, 2007: 6); there are no fundamental differences between the two forms of cocaine, except for the racial differences in their users. In fact, over 90% of those convicted under this statute were black Americans, leading the defendant in the federal court case of United States v. Clary in 1994 to challenge this sentencing disparity as racially discriminate (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 367). The court upheld it because he could not prove the purposeful discrimination of those who created and passed the law, despite the severe racial gap in convictions it created. The drastic difference in mandatory sentencing was reduced by President Barack Obama’s Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, but only for 18 grams of powder cocaine to equal one gram of crack cocaine (Banks, 2016), so black communities are still penalized for these offenses at much higher rates.

The Effect of Felony Disenfranchisement on Black Communities

With black Americans’ clear and substantial overrepresentation in the prison population, they are far more likely to have longer criminal records compared to white Americans. These previous convictions can then be used against them in future contact with the criminal justice system, such as police conducting an investigatory stop and arresting them on no reasonable suspicion except a previous criminal conviction, prosecutors assigning more severe charges, or judges handing down longer sentences (Banks, 2016). The policies of the War on Crime and War on Drugs eras of the late 1900s still have a hold on black communities today; although some of the sentencing disparities have been reduced, the criminal stigmatization and lack of education and employment opportunities in these neighborhoods have not. Black communities as a whole are affected by their overrepresentation in the criminal justice system, even those who are not in contact with the system through the ‘invisible punishments’ detailed by Brewer and Heitzeg (2008). They include the legal forms of discrimination against convicted felons in all areas of life, such as employment, education, housing and access to public benefits (Alexander, 2012: 2). Drug felons, which are disproportionately black Americans due to the War on Drugs policies, are permanently barred from access to public benefits such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, public healthcare plans, food stamps, unemployment payments, public housing and public financial aid for a college or university education (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 629). The modern form of legalized racism exists in legislation permitting the disenfranchisement of felons, even after their release, which involves the deprivation or limitation of certain rights, especially the right to vote (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 628). In 14 states, people with a felony on their record can never vote again, 48 states bar prison inmates from voting and 32 states disenfranchise felons who are on parole (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 628). One cannot help but draw parallels between the Black Codes and Jim Crow era limitations on black Americans’ right to vote; instead of poll taxes or literacy tests (Hassett-Walker, 2021), having a felony on one’s record often results in their voting rights being revoked. In addition to having their political voice silenced through deprivation of the right to vote, 25 states permanently ban previous felons from ever holding public office or working in childcare, teaching and law enforcement (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 629). As of 2013, one third of drug arrests and 45% of federal prisoners on drug charges were black Americans, who still only constitute 13% of the overall United States population (Williams, 2020). With a significant amount of black Americans disenfranchised from felony drug records, unable to work or get an education, what are they to do but turn to illegal activities in order to support their families? This cycle of criminalizing an entire sector of the population and then legalizing their discrimination based on the criminal status that was forced upon them continues today, therefore the phenomenon of punitive segregation does as well (Garland, 2002: 142). The modern criminal justice system has taken funding away from making urban black communities productive, prosperous homes for people to thrive in, and instead has overpoliced their streets, mass incarcerated their citizens and further prevented them from rebuilding their lives once they are released from prison.

Many Americans who agree with the colorblind ideology that institutionalized racism no longer exists say that the criminal justice system effectively works as it is intended to, and they are partially correct. The system as we know it today was founded in the roots of slavery and black Americans’ societal subordination, without significant attempts to rectify the aftereffects of policies such as the segregated, underfunded resources of the Jim Crow era. Historically, the criminal justice system’s intended purpose has been to uphold the values of white supremacy through the overcriminalization of black America; in that right, it has been successful. True justice, however, has been lost in the passage of ‘colorblind’ legislation targeting low-income black neighborhoods that are ravaged by poverty, lack of education or employment opportunities and widespread disenfranchisement through disproportionately long criminal records due to the War on Drugs. As previously stated, the overcriminalization and subsequent mass incarceration of black Americans in the decades following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has led to their striking overrepresentation in the prison population. Once imprisoned, they are confined in the chains of today’s modern, ‘colorblind’ slavery: the prison industrial complex, which will be expanded upon in the following chapter.

5. The Prison Industrial Complex: Modern Slavery

The Origins and Creation of the Prison Industrial Complex

The modern period of the American criminal justice system is marked by colorblind ideology that allows for white supremacist values to be discreetly, yet openly, upheld under the facade of criminal justice. The blatant overrepresentation of black Americans in the prison system goes unquestioned and accepted by news media and the general public because the possibility of racial discrimination in criminal legislation is dismissed by ‘colorblind’ policymakers; to reiterate, black Americans are 38% of prisoners but 13% of the general population as of 2016 (Nellis, 2016), largely due to the policing and sentencing policies during the late 1900s. Modern institutional racism, much like its predecessors, is directly tied to capitalist financial interests. Slavery in its original form was a source of free labor for southern states to exploit for their economic benefit, the subsequent Black Codes and Jim Crow laws required black workers to sign employment contracts that ensured they were paid poverty wages in order to create a larger profit margin for their employers, and today’s prison industrial complex exploits the labor of prison inmates to benefit private companies and the national economy. This system was able to expand due to the ‘tough on crime’ policies within the past 50 years, resulting in the mass incarceration of large portions of black Americans. This sharp increase in the prison population in such a short amount of time created overcrowding in prisons and the government turned to private prisons, institutions that require inmates to work in order to make the prison a profit (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 349). The growth in prominence of private prisons spiralled into the prison industrial complex, where the government and private industry converge to expand the criminal justice system for financial gain, at the expense of black Americans and their entire communities.

The current racial disparities in the prison population nearly mirror those of the convict leasing and debt peonage systems that were in use from the abolition of slavery until the 1940s (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 636), representing the deeply rooted historical view that the American system views black labor as a cheap and dispensible source of profit. The prison industrial complex serves the interests of the elite class, including politicians who exploit crime for votes, media companies who profit from exaggerated crime reporting and private companies who make an average of $250 million in annual profit for supplying and running prisons (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 637). This industry is given over $50 billion in tax dollars annually, an amount that could easily be invested in impoverished urban neighborhoods; so why, if crime is so rampant in these areas, would the government not try and stop crime at the source by providing more resources for education and job creation? Simply put, the government values the economic benefit of exploiting the vulnerable social classes over their civil rights. Garland’s (2001) reference to America’s prioritization of individualism over collectivism only applies to those being mass imprisoned; the elite class as a collective benefits from criminalizing certain individuals so the public does not question their incarceration, segregating them from society and exploiting their labor. The financial and political benefits reaped from the prison industrial complex lead to targeted policies that guarantee an endless supply of laborers, including the sentencing enhancements from the War on Crime and War on Drugs eras, higher allowances for juveniles to be sentenced as adults, reduced rehabilitative, educational or vocational programs inside prisons (Brewer and Heitzeg, 2008: 637) as well as the previously mentioned invisible punishments affecting entire communities. These policies heavily encourage recidivism among released convicts, who are given little alternative options or rehabilitative guidance.

The prison industrial complex continues to function largely due to the loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment used during the Black Codes era for the practice of convict leasing, which states ‘Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States’ (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 359). The course of action for the American government has always been fairly straightforward: criminalize behaviors specific to certain demographics, namely black Americans, without explicitly targeting them, in order to incarcerate them and place them in legalized slavery without the risk of violating their Constitutional rights (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 382). Similarly to racial discrimination of the police, prosecutors, court systems and policymakers, the prison industrial complex would be nearly impossible to challenge as racially discriminate because of the USSC ruling in McCleskey v. Kemp requiring purposeful discrimination to be proven (Banks, 2016). Although black Americans are the demographic most affected by this industry and all of the policies keeping them trapped in it, the race-neutral nature of the legislation will uphold the colorblind ideology that no race is being directly targeted.

The New Form of Convict Leasing: Privatized Prisons

The private industry has consistently been involved in the practice of prison labor, dating back to the Black Codes era of convict leasing, where prisons would lease inmates to private companies to work directly for them. Although convict leasing was abolished in the early 1900s, many of the inhumane practices remain, such as the reinstatement of chain gangs in many southern states, where the black inmate population averages at 65% (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 361). This act of forced labor involves a line of inmates chained together by the ankles, often with weights on their legs restricting their mobility, doing manual labor for upwards of twelve hours per day. In Georgia, the private company Bone Safety Signs is contracted with the Georgia Department of Corrections, allowing them to operate production plants directly in prisons using inmate labor (Raza, 2011: 161). In this state, over 60% of inmates are black and leave their sentences with felony disenfranchisement and the other forms of legalized discrimination against felons (Raza, 2011: 161), making their reincarceration and reentry into the prison industrial complex inevitable. The working inmates manufacture everything from office furniture, road signs, janitorial chemicals and more, receiving a pay that is automatically deducted for expenses like their room and board, ‘victim restitution’ payments, child support, payment to the private company or the direct cost of their incarceration (Hammad, 2019: 77). These wage deductions are permitted by the 1979 Justice System Improvement Act, which requires prisons and private companies using prison labor to pay inmates a wage matching that of non-prisoners in that state doing the same job, seemingly to guarantee their fair treatment and pay. However, the same provision lists all the possible reasons to deduct money from inmates’ paychecks, leaving them with an average of $2 per day for personal use (Garcia et al., 2020). The prisoners are essentially paying rent to be incarcerated, a place they are often unjustly placed. In addition to most of the inmates’ paychecks going directly to the prison, the prison system still receives billions of dollars annually in taxpayer money, for the purpose of paying for inmates’ incarceration (Hammad, 2019: 78). In areas where private companies are involved in using prison labor, the profits are split between the company and the prison itself. The private industry has the opportunity to make billions in profit between cheap labor and the vast amount of goods sold at market prices, as well as the 1979 Justice System Improvement Act provision allowing them to claim tax write-offs for using prison labor (Hammad, 2019: 77). Tax write-offs are commonly used by businesses to avoid paying taxes on expenses paid for business-related goods or services. For example, the BP oil company responsible for the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico contracted prisoners to work on site cleaning it, receiving a tax credit of $2,400 per prisoner (Hammad, 2019: 77). This incentivizes corporations to use as much prison labor as possible, because they can maximize their profit through claiming the labor as a tax write-off. If they have more tax credits than taxes they owe, they will receive a check for the remaining balance; in theory, companies can use prison labor not only to completely avoid taxes, but actually be paid by the government.

The modern prison system alarmingly resembles the system of slave labor in the 18th and 19th centuries. The only difference is that black people are not explicitly targeted by the government’s legislation allowing the system to continue, but the basic structures are the same; the government, politicians and private industry mutually benefit from legalizing the exploitation of the labor of black people in America, using the media as a tool to shape the public’s perception of black Americans and accept their status as second-class citizens. The modern prison industrial complex is the culmination of the United States’ social and criminal justice policies throughout the country’s history, from the original practice of slavery to the modern policies that criminalize black Americans as a justification for restricting their rights. As civil rights activist Malcolm X stated, “As long as the oppressor controls the legislative, judicial and enforcement machinery of the legal system, a direct relationship is established between law and oppression” (Weaver and Purcell, 1997: 352).

6. Conclusion

Upon examining the historic roots of systemic racism in America’s institutions and all of its shifts, this dissertation has argued that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 did not eradicate it, but simply mark another point of evolution. There is a longstanding trend of the criminal justice system simply masking the policies of institutional racism to fit the social norms of the time; when slavery was abolished, the Black Codes were introduced to uphold the exploitation of black Americans’ labor through forced labor and employment contracts guaranteeing the lowest pay possible (Hassett-Walker, 2020), without classifying it as slavery. The Black Codes were then replaced by Jim Crow laws, legalizing racial segregation under the premise of ‘separate but equal’ facilities for blacks and whites, although that was not fulfilled. Given the evolutionary nature of institutional racism in America, it is not unreasonable to assume that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is the modern point of evolution towards the discriminatory War on Crime and War on Drugs policies that still affect black Americans today, in the form of colorblind legislation. The historic persistence of racially discriminate legislation, when coupled with the implicit racial biases ingrained in the criminal justice institutions and increased discretionary powers of actors within the system, has created an environment where the mass incarceration of black Americans is accepted by the general public (Banks, 2016). The precedent for defending colorblind legislation is set in the USSC case of McCleskey v. Kemp, requiring purposeful discrimination to be proven on the part of criminal justice actors, and largely prevents black Americans from legally challenging their discrimination (Banks, 2016). The mass imprisonment of black Americans through criminalizing their civil rights protests and over-policing black neighborhoods results in a large percentage of black Americans being disenfranchised and unemployed. Their reentry into the prison system is nearly inevitable, achieving the goal of the prison industrial complex to have a constant labor supply as well as reinforcing the prejudiced view of black Americans being inherently criminal.

Historically, every time black Americans have been legally discriminated against it continues widely unquestioned by the general public; slavery was defended as being necessary for the economy, Jim Crow laws were justified as keeping public order and preventing crime by segregating the races (Banks, 2016), and the prison industrial complex operates under the guise of punishing criminals, who the public believes deserve harsh work conditions to reform them. The conditions of the prison industrial complex, as well as the disenfranchisement of thousands of black voters, display stark similarities to the forced labor and convict leasing practices of the Black Codes and Jim Crow eras, drawing the conclusion that America is not as racially progressive as its leaders claim to be.

References

Alexander, M. & West, C. (2012) The new jim crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York, United States: The New Press.

American Sociological Association, (2007), Race, ethnicity, and the criminal justice system.

Balko, R. (2020) Opinion | there’s overwhelming evidence that the criminal justice system is racist. here’s the proof. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/opinions/systemic-racism-police-evidence-criminal-justice-system/.

Banks, C. (2016) Criminal justice ethics, 4th edition Sage Publications.

Beauchamp, Z. (2020) What the police really believe. Available online: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/7/7/21293259/police-racism-violence-ideology-george-floyd [Accessed Apr 8, 2021].

Berdejó, C. (2018) Criminalizing race: Racial disparities in plea bargaining. Boston College Law Review, 59 .

Brewer, R. M. & Heitzeg, N. A. (2008) The racialization of crime and punishment: Criminal justice, color-blind racism, and the political economy of the prison industrial complex. American Behavioral Scientist, 51 (5), 625-644.

Brooks, D. (2020) The culture of policing is broken. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/how-police-brutality-gets-made/613030/ [Accessed Apr 8, 2021].

Chaney, C. & Robertson, R. V. (2013) Racism and police brutality in america. Journal of African American Studies, (17), 480-505.

Collins, A. (1998) Shielded from justice: Police brutality and accountability in the united states. Human Rights Watch.

Columbia Justice Lab, (2020), Racial inequalities in new york parole supervision.

Crow, M. S. and Johnson, K. A., (2008), Habitual-offender sentencing A multilevel analysis of individual and contextual threat. [Accessed: Apr 11, 2021].

Cummings, A. D. P. (2012) All eyez on me: America’s war on drugs and the prison-industrial complex war on – the fallout of declaring war on social issues. Journal of Gender, Race & Justice, 15 (3), 417-448.

Garcia, C., Rafieyan, D. & Morgan, D. (2020) The uncounted workforce : The indicator from planet money. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/06/29/884989263/the-uncounted-workforce [Accessed May 1, 2021].

Garland, D. (2001) Mass imprisonment: Social causes and consequences .

Garland, D. (2002) The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society.

Hammad, N. (2019) Shackled to economic appeal: How prison labor facilitates modern slavery while perpetuating poverty in black communities. Virginia Journal of Social Policy & the Law, 26 (2), 65-91.

Hassett-Walker, C. (2020) The racist roots of american policing: From slave patrols to traffic stops. Available online: http://theconversation.com/the-racist-roots-of-american-policing-from-slave-patrols-to-traffic-stops-112816 [Accessed Mar 28, 2021].

Hassett-Walker, C. (2021) How you start is how you finish? the slave patrol and jim crow origins of policing. Civil Rights and Social Justice, 46 (2), .

Hegarty, J. (2017) Who watches the watchmen? how prosecutors fail to protect citizens from police violence. Journal of Public Law and Policy, 37 (1), .

Hinton, E. & Cook, D. (2020) The mass criminalization of black americans: A historical overview. Annual Review of Criminology, 4 .

King, R. S. (2006) Jim crow is alive and well in the 21st century: Felony disenfranchisement and the continuing struggle to silence the african-american voice. Souls, 8 (2), 7-21.

Lhamon, Catherine E. et al, (2018), Police use of force: An examination of modern policing practices.

Moran, L. (2021) Laura ingraham spins chauvin conviction, claims systemic racism is ‘the big lie’.

Nellis, A., (2016), The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons.

Nittle, N. K. (2021) How the black codes limited african american progress after the civil war. Available online: https://www.history.com/news/black-codes-reconstruction-slavery [Accessed Mar 29, 2021].

Onion, A., Sullivan, M. & Mullen, M. (2021) Jim crow laws. Available online: https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws [Accessed Mar 31, 2021].

Owen, P. (2020) Tucker carlson: BLM protesters are ‘thugs with no stake in society’.

Raza, A. E. (2011) Legacies of the racialization of incarceration: From convict-lease to the prison industrial complex. Journal of the Institute of Justice & International Studies, 11 159.

Rios, V. M. (2006) The hyper-criminalization of black and latino male youth in the era of mass incarceration. Souls, 6 (2), 40-54.

Sastry, A. & Bates, K. G. (2017) When LA erupted in anger: A look back at the rodney king riots. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2017/04/26/524744989/when-la-erupted-in-anger-a-look-back-at-the-rodney-king-riots [Accessed Apr 7, 2021].

Sawyer, W., (2019), How race impacts who is detained pretrial .

Smiley, C. J. & Fakunle, D. (2016) From “brute” to “thug:” The demonization and criminalization of unarmed black male victims in america. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26 (3-4), 350-366.

Smith, T. & Bartelme, G. (2015) Pull over five things to remember when you see the blue lights. Available online: https://www.postandcourier.com/archives/pull-over-five-things-to-remember-when-you-see-the-blue-lights/article_c898fb10-8905-5eba-ba01-7b2d15312fb4.html [Accessed Apr 15, 2021].

Stevenson, B., (2017), Lynching in america: Targeting black veterans.

Weaver, C. & Purcell, W. (1998) The prison industrial complex: A modern justification for african enslavement symposium: Law and the politics of marriage: Loving v. virginia after thirty years: Comment. Howard Law Journal, 41 (2), 349-382.

Welsh, D. (2009) Racism and the law: Slavery, integration, and modern resegregation in america. 2009 (2), 479-488.

Williams, M. & Sapp‐Grant, I. (2000) From punishment to rehabilitation: Empowering African‐American youths. Souls: Critical Journal of Black Politics & Culture, (1), 55-60.