Abstract

Pornography has become the leading sex education resource and therefore, has developed misleading perceptions of what defines sex and female sexuality. Feminist Pornography has formed a solution to this issue as the films that are made are directed and produced by women with priorities of ethical production, inclusivity and female orgasm. In this research, I will explore the role it has in society.

The three critical areas of focus I explore are the views of anti-pornography feminist activists and questioning their strategies on how to stop the objectification of women in Porn. I explore societies perceptions of female sexuality and question if Feminist Pornography could make a significant impact on social attitudes to Porn, female sexuality and sex. Lastly, I have explored what defines the Female gaze, the benefits of it, and if there is a gender difference in the gaze used.

I used email interviews as the qualitative method of research where I have interviewed two academics and a Feminist Erotic, Indie, Film-maker/Director Erika Lust. The research highlighted issues of shame, embarrassment and insecurity attached to watching Porn, the dangers surrounding eliminating all Porn and questioned the sustainability of Feminist Porn without commercial success.

To conclude, I agree there is a role for Feminist Pornography in society, but the impact it can have is all dependent on the sustainability of the market. I would recommend further research to understand how Feminist Porn maintains their standards of ethical production, by observation and interviewing, to understand the experiences of those on the set of a feminist Porn film. I think more research needs to be done in this area to understand the benefits of Feminist Pornography on society.

Author: Gabrielle Kear, April 2020

BA (Hons) Sociology and Anthropology with Gender Studies

Acknowledgements

Firstly I would like to say a huge thank you to my supervisor/tutor Bev, you were so incredibly supportive, kind, encouraging and never failed to make me laugh. I’m so glad I retook the year just purely for having the honour to work with you.

There are not enough words to describe how grateful I am for the next person, my Mum, Mumma Maxine and my best friend. Thank you for forever being at the end of the phone, supportive through all the tough times and keeping me focused throughout the last 4 years. I wanted to make you the proudest Mumma this year, and I really hope I have.

I would also like to give a special thanks to my amazing Dad for continuously checking in on me, those messages and calls never went unnoticed. I don’t say it enough, but I love you.

How can I forget my amazing and loyal friends, I don’t want to miss a name, but I will just include three that have never budged – India, Molly and Michelle – I love you. My friends are without a doubt the best thing that has happened to me in the last 4 years, growth, love and support – there is truly nothing better.

And last but definitely not least, My gorgeous, I love you. Thank you for loving me first.

List of Abbreviations

- Pornography (Porn)

- Woman Against Pornography (WAP)

1 Introduction

Feminist Pornography is an umbrella term that represents consensual, safe and representative Pornography. It encompasses a broad range of porn genres, but the difference is it is produced independently by a female feminist director, away from the free tube sites. It has a niche market and is part of a revolutionary concept that recognises the importance of female pleasure and an ethical production which creates an “environment where performers can explore their sexuality safely” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust).

Feminist Pornography is not categorised as Erotica but still has to arouse the viewer (erotic). “Eros (meaning Erotica) refers to spiritual, rather than to animal, pleasures” (Kear, 2020: Interview B) and by definition is concerned with the “matters of love” (OED, 1933) or “pertaining to the passion of love” (OED, 1891). Erotica is “softer” (Assiter & Carol, 1993:25), suggesting Feminist Porn is passive to the often rough and passionate mass-produced mainstream Pornography that has a male focus. This othering of women’s Pornography is arguably a metaphor for female sexual repression ingrained in our patriarchal society.

In my research, I have decided to explore the role of Feminist Pornography in Society. My initial argument is that as a feminist, feminism equals choice and choice of what one may do with their body and exploring the truth in the statement of “the answer to bad porn isn’t no porn, it’s to try and make better porn” (Ryberg & Mulvey & Rogers, 2015:80). I will be exploring whether or not having more women in the production process (writing, directing and producing) will create a female gaze and a safer environment for the performers. I will also be exploring the views of anti-pornography feminist activists and questioning their opinions on the strategies to stop the objectification of women in Pornography. Furthermore, lastly, I will be exploring societies perceptions of sexuality and questioning if Feminist Porn could effectively benefit society by changing their views of female sexuality.

Feminist Pornography creates an “interpretive community held together precisely by the common concern with safe space” (Ryberg & Mulvey & Rogers, 2015:80). From safe space, comes an ethical production process which includes multiple steps to ensure performers feel protected and heard. One of the ways is through a fair wage for all performers and crew, a pre-production process where “everything about the sex scene is discussed in advance and agreed upon” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust) to ensure all performers feel comfortable and can voice any changes they would like to make. The performers highlight their boundaries, their usual sexual practices and communicate anything they want to try. Erika Lust (2020) expresses how she does not direct the sex scenes; the performers are in control, this is common amongst most Feminist Pornography as the lack of directing creates authentic, emotive and raw sexual experiences for both performer and viewer. Feminist Pornography is one example of the shift from sterile, directed Porn to personalisation which Feona Attwood sees as the “rhetoric of the authentic” (Attwood, 2010:91).

Before assuming this is just “another brand of porn” (Interview 2, 2020), let me explain the difference between Mass-Produced Mainstream Pornography and Feminist Pornography. Mass-produced Mainstream Pornography is available on free internet sites with 6.83 million video uploads and 42 billion visits (Porn hub, 2019) to Pornhub (one of the many internet porn sites) in the last year. In comparison, Erika Lust may only create 26 short erotic films a year, which is a significantly lower statistic. Most Feminist Pornography is purchasable; this price ensures that all performers receive fair wages. The performers in mass-produced mainstream Porn have one body type; for females, it is the highly sexualised Jessica Rabbit figure with large breasts, small waist, a large bottom and a hairless body. The male performers are tanned, toned and usually have an abnormally large penis. If the films feature people of different ages, abilities, body types and races, they are usually objectified and fetishised for their differences. The titles of these videos include “very sexy midget” (Porn hub, 2020) and “hot chubby girl fuck and facial” (Porn hub, 2017). In Feminist Pornography, representation is high on the agenda, not only do they represent women but they celebrate all diversities intending to show relatable and consensual sex with less body comparison for those watching.

In my research, I noticed a pattern in the specific use of language, favouriting the word Erotic and avoiding the word Pornography. Like most derogatory words that have negative connotations, there is an opportunity for the word to be reclaimed and used with positive, empowering intentions. This empowering focus is what drew me to the title Feminist Pornography, by altering something once “ugly, violent, chauvinistic and shameful” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust), it can be changed to become an empowering, well-made resource. However, to my surprise, Erika Lust disagreed and chose the word Erotica instead to represent her work. She did not want to be associated with the stigma attached to the word Pornography. Erotica is associated with “beauty, cinema and context” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust) and demonstrates her different approach. In my opinion, Erotic suggests a form of cinema that does not push the boundaries, but Feminist Pornography implies it does.

2 Rationale

Pornography has become societies central educational resource for sex; therefore, Pornography’s content may seep into reality. With “115 million visits” (Porn hub, 2019) to Porn Hub per day in 2019, it is apparent that Porn can have a considerable influence over our society. However, the content of Pornography is not necessarily an accurate representation of sex, intimacy, body image and sexual performance in our society. Young people only see one type of sex shown on screen, although it comes in different forms with the most popular in 2019 being Amateur, cosplay, mature and bisexual, there is a general lack of consent, open communication, a realistic body image without being fetishised (Plus-size women) and tender loving sex. Therefore, young people watch Pornography and believe what they see on the screen, and when they come to have sex themselves, they have false expectations of what they or their partner can do. Feminist Pornography would provide an alternative resource of information, some anti-porn campaigners believe the criminalisation of Pornography would be most effective, but this is unrealistic – with “14 video uploads” (Porn Hub, 2019) per minute on one Porn website alone, we are making more Porn than we have time in the day. Feminist Pornography is no less kinky and sexy as the Porn we are used to. Instead, it just incorporates all the aspects of real sex that is not shown on the R-rated movies online.

Tristan Taormino defines Feminist Pornography as a genre dedicated to “gender equality and social justice. Feminist porn is ethically produced porn, which means that performers are paid a fair wage and they are treated with care and respect; their consent, safety, and well-being are critical, and what they bring to the production is valued. Feminist porn explores ideas about desire, beauty, pleasure, and power through alternative representations, aesthetics, and filmmaking styles. Feminist porn seeks to empower the performers who make it and the people who watch it” (Breslaw, 2013).

It was a program on Channel 4 called ‘Mums make Porn’ that sparked the idea. This series featuring Erika Lust where a group of mothers joined together, a diverse range of ages, religious and racial backgrounds and decided to write, produce and direct Pornography. Their films would focus on consent, communication and sexual exploration in a safe space. The aim was to create films they would be comfortable enough to show their adult children. I knew about the work of Erika Lust before, therefore seeing her on Channel 4 only fuelled my curiosity in her work. She is a multi-award winning Indie Erotic film director, and she describes her work as follows “the shift towards consuming organic produce instead of fast food is reflective of a more ethical, intelligent society. We want to encourage this type of consumerism within adult entertainment, through ethical production and distribution” (Lust, 2019). I have always been very open about sex, sexuality and intimate relationships; therefore, it was a natural transition to become engrossed in the movement she is creating as an activist. This research project is a testament to my knowledge and interest in the political importance of women’s pleasure.

When I initially tell people about my topic, they flinch at the word Pornography. To me, this reaction is a physical representation of the stigma against it. However, once I explain Feminist Pornography in more depth, the response is full of curiosity and excitement, often following with an offer to proof-read the full written dissertation. This reaction is a physical representation of the importance of Feminist Pornography and how it can reduce stigma around the filmed sex industry. I chose to study the role of Feminist Pornography because it is refreshing, progressive and representative of all people, not just women. It is an educational resource, an art form and something that people should know about, not just to benefit themselves and their intimate relationships but also to stop the stigma surrounding consensual sex on screen.

3 Context

One of the running themes throughout this dissertation is feminism and the suppression of women through their sexuality and roles in the patriarchal society. Anti-pornography feminism focuses their attention on misogyny in Pornography. Throughout all industry fields in society, women’s opinions, bodies, sexuality and roles are ignored. Men consider women as a health risk, “contaminating or corrupting both to man’s body and to his morality” (Gilmore, 2001:139). Feminism is a reaction to this, with “the awareness of the special oppression and exploitation that all women face” and “the willingness to organise and fight against women’s subjection in society” (Emerson, 1975:6). Capitalism and Industrialisation meant women were “super-exploited as workers” (Emerson, 1975: 8) enslaved in the home and factories. However, this created an environment for “new forms of protest – a women’s liberation movement” (Emerson, 1975: 8).

Feminist history divided into four waves; the first wave incapsulated the Suffrage movement “which acted as a powerful unifying force” (Banks, 1986: 72), led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christobel. The aim was for upper/middle-class women to gain the vote, therefore excluding women of colour and lower classes. Their organisation (Women’s Social and Political Union) put on massive demonstrations, “broke windows, blew up buildings, destroyed other forms of property and mercilessly heckled all politicians” (Emerson, 1975: 22). In 1918, the Representation of the People Act passed, allowing “women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification to vote” (Parliament, 1989). East London Federation of the Suffragettes was created by Sylvia Pankhurst to extend the vote to working-class women and incorporate their worker’s rights. Ten years later, all women over the age of 21 were able to vote in the Equal Franchise Act of 1928 (Parliament, 1989).

After gaining the right to vote for most women, second-wave feminism of the 1960s and ’70s was more about fighting patriarchy, inequality, discrimination and to ultimately “accord to women the rights that men hold ‘naturally’” (Whelehan, 1995: 29). The distinct difference of the women’s movement to other liberation campaigns at the time was the critical slogan “the Personal is Political” (Whelehan, 1995: 13) to raise women’s consciousness and “awaken women to the injustices of their secondary social position” (Whelehan, 1995: 13). The importance of the institutionalisation of the family unit and “monogamous heterosexuality as the desired norm are crucial factors in women’s oppression” (Whelehan, 1995: 75). Therefore, by advocating and normalising childcare and switching domestic roles, it removes the necessity for women to have a triple shift (reproductive, productive and community roles) in society.

By the end of the second wave, the Feminist Sex Wars had emerged (1970’s). During this period, Radical feminists formed an anti-pornography campaign ‘Women against Violence in Pornography’ protesting for the elimination of all pornography. This is when liberal ‘Pro-Sex’ Feminists responded.

Third-wave feminism of the 1990s acted as a continuation of the second wave, questioning the media’s opinions on beauty, womanhood, sexuality, femininity and masculinity and how it influences young women. There is more of a focus on diversity and seeing women’s lives as intersectional, incorporating race, ethnicity, class, religion, gender, and nationality and the importance of being a feminist.

Fourth wave feminism is the most recent form of the liberation movement for women, starting in the early 2000s, using social media and the internet as resources to raise awareness of feminist issues and empower those who identify as women. This movement is “defined by technology: tools that are allowing women to build a strong, popular, reactive movement online” (Cochrane, 2013). One famous female liberation movement was the #MeToo campaign which trended globally on Twitter encouraging women to speak up about hidden assaults following the Harvey Weinstein sexual assault allegations. Fourth wave feminism has strong themes of empowerment and prevention with campaigns against rape and for consent. Pornography has arguably become normalised during this wave of feminism, and therefore there has been a growth of sexual educators online, the importance of female sexual pleasure, desire and sexuality and Feminist Pornography.

4 Methodology

My research question is ‘What is the role of Feminist Pornography in Society?’ I decided to structure the research questions based on three areas of focus (shown below); that way, I could include the discussion of my findings within the three chapters, rather than separate them.

1. A female behind the lens – Does this change the gaze?

2. Feminist Pornography – Agree or disagree?

3. *The Cum shot* – What are the perceptions of sexuality?

My research explores the opinions of University Academics and Erika Lust, a Feminist Erotic Film Director. Although Feminist Pornography is a relatively new film genre, niche and form of activism, there is research regarding feminism and Pornography, female sexuality and Pornography being one of the largest. My experience of researching this topic was challenging; I discovered it came with a lot of shame and prejudice which led to a lack of participants, which is another reason why it is so important to write about it.

The use of Feminist Methodology:

While no one definition of feminist research exists, many feminist researchers identify characteristics which distinguish it from traditional social science research; it is research that studies women, or that focuses on gender.

Judith Cook and Mary Margaret Fonow (1986) established five basic epistemological conventions in feminist methodology. These include taking of women and gender as the focus of analysis, the importance of consciousness-raising, the rejection of subject and object (this means valuing the knowledge held by the participant as being expert knowledge) and acknowledging how research valued as “objective” always reflects a specific social and historical standpoint, a concern with ethics (throughout the research process and within the use of analysis results), and an intention to empower women and change power relations and inequality (Kaur & Nagaich, 2019:3).

By doing Feminist research, the most favourable option for collecting data was Qualitative, more specifically, semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviewing creates an environment which avoids control over those interviewed (Reinharz, 1992:20) and “openness, engagement (… and) egalitarianism” (Reinharz, 1992:27). Feminist researchers argue that traditional social theories have often marginalised or rendered insignificant women’s life-worlds. I wanted to explore “issues of social change and social justice for women and other oppressed groups” (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2007:114) and Feminist Pornography which has proved a sensitive topic which people feel uncomfortable talking about openly.

Participants involved:

I only received replies from three participants, two Academics and one Erotic Feminist Filmmaker and Director, named Erika Lust. I interviewed academics (men or women) who may have an interest in the field (not necessarily directly but related to some aspects) because practically they are the easiest to access. It was also crucial for me to have an academic understanding of the sociological themes in the research. Based on their published work, most academics had little to no interest in Pornography or Feminist Pornography, so the option to only read and reference their published work was not an option. Instead of interviewing them for their knowledge of the topic, I wanted to interview them for their understanding of sociological and criminological themes and theories they may be able to pick up in the questions I asked. Their responses focused on minor details that others may have brushed over with the end response being informative and enlightening.

Please refer to Figure 1 in the Appendices for an Extract of the questions I asked University Academics. And Figure 2 for an extract of the questions I asked Erika Lust.

Method Step 1 – The Start:

I started the research by approaching female academics in person, as being feminist research, I was looking for “self-revealing and consciousness-raising potential of woman-to-woman talk” (Reinharz, 1992: 23). After approaching the first person, there was a concern I was too selective; it was then recommended I send an open-ended email out to multiple people of all intersections, departments and Universities and ask if anyone was interested in anonymously discussing Feminist Pornography. I chose these academics based on their published work under their profile on the University website. However, no one I chose had a specific interest in Pornography; their published work suggested they either had an interest in victimisation, media, online film, deviance or gender studies. Choosing academics was partially successful; I sent the email to a total of 12 people with one response and later a second response. Please refer to Figure 3 in the Appendices for an Extract of that email.

Method Step 2 – The Middle:

After speaking to a few academics who received the email, they expressed they did not want to take part and therefore chose not to reply. After seeking advice regarding the lack of responses, the Head of the Department suggested the group email may have come across impersonal, often with email recruitment, there is an “information overload, many people delete invitations before they are read” (Meho, 2006:6). Therefore, after limited responses, I began to contact the respondents personally for the second time, but this time through email. I chose to change my research to Email Interviews as for Erika Lust specifically, we were “geographically far apart” (Meho, 2006:3), so an interview through email was the most comfortable and accessible option with her busy schedule. For all participants, it meant they could revise their answers and articulate their opinions without rushing or forgetting something. Email Interviewing is an adaptable method which is a “viable alternative to face-to-face and telephone interviewing” (Meho, 2006:2) that has a limit of time, money and location.

Some feminist researchers argue social science research is often used as a tool for promoting a sexist ideology therefore an alternative up to date method may be more informative and less bias. Through this method, I gained a third person interested (this person did not take part in the research) and a rather challenging, unpleasant email from a male professional. Because of the anonymity of email, possible participants can “be less friendly to the interviewer” (Meho, 2006:7); therefore, the response I received was in some ways understandable.

Method Step 3 – Challenges:

Initially, I found multiple compelling issues regarding the response I received from the male professional. The first was the idea that Pornography or more accurately, Feminist Pornography was described as a ‘Taboo’ subject. Taboo signifies forbidden and prohibited. As an academic, it is interesting that Pornography is viewed as taboo and not to be spoken about but a topic like incest, rape and paedophilia are so widely discussed in many research projects and lectures. These topics you would assume would be taboo or more sensitive than Pornography because of the harm that it causes people. In my opinion, rape, paedophilia and incest is an unthinkable, unique human experience and can be talked about objectively.

However, some argue Pornography is equally as “morally corrupting” (Randall, 1989:121) and also “ranks with crime, delinquency, drug abuse, sexual promiscuity, and other deviations associated with social disorder and disintegration” (Randall, 1989:121). The challenges I faced with the recruitment of participants suggested Pornography is associated with judgement and prejudice. Even though some may see it as a taboo subject, the rate of Pornography streaming remains high, in 2019 there were “42 billion visits to Pornhub” (Porn hub, 2019) alone, which suggests Porn is normalised in private but not in professional environments. Masturbation and sex overall remain unspoken in the professional environment.

Furthermore, he takes paticular issue in the fact I did not state the definition of Pornography in the original email. This implies the act of admitting you know the definition of Porn is shameful. I think it is also important to reiterate I did not ask for their personal experiences of Pornography, as you can see in Figure 3 in the Appendices of the sent email, I aimed to ask questions that they could answer based on their existing research acquired through academia. The second participant who agreed to partake discussed with me the research and their response and opinions were very similar. They told me they initially were not comfortable answering the questions because of the subject matter ‘obviously’. I found it interesting that it was phrased in this way to suggest that everyone should feel uncomfortable answering questions regarding Pornography. This embarrassment suggests there may have been a gender issue, as a woman asking participants about Pornography may have made them uncomfortable. Could this have been an issue if I was male and asked the same questions?

Limitations and Reflections:

1. Interview only industry workers: I initially only wanted to question the opinions of those involved in the industry, such as female writers, producers and directors. However, although being able to interview one, practically, it was difficult to access more. If I had started the practical research at an earlier date, it would have given me more time to contact a wide variety of women in the industry. Another solution is to explore the topic in more depth through a Postgraduate Dissertation. Including academics in the research as an alternative became a favourable decision because it gave me a well-rounded view of an outside but still influential perspective on the effects of Feminist Pornography on society as a whole.

2. Female Participant focus: When choosing whom to approach to take part, I chose only female participants because the topic overall talks mostly about the benefits to women in society. However, I came to understand that by assuming only women would be interested, I was ignoring feminists of any gender that may provide an equally exciting insight.

3. Lack of responses: One possible reason was the time of year I chose to send out the emails; all of the Academics I included in the email were also lecturers at a multitude of Universities. I sent the email February 2020 during a time where most lecturers are busy marking, responding to emails and meetings with students about final year dissertations. On reflection, if I were to repeat this research, I would approach academics further in advance.

4. Email Interviews and Consent: By changing to Email Interviewing, there was a definite consent issue. There was a loss of some participants because they had no way of knowing if the answers would remain confidential. Although in all corresponding email’s it was repeated that the information would remain confidential and anonymous (unless they decided against this).

Here are examples of how I told the participants:

“the answers will remain anonymous unless you ask for them not to be” (Kear, 2020: Interview A).

“All of the responses will be anonymous and there will be no mention of your name (unless you feel you want to) within the written dissertation” (Kear, 2020: 12 participants).

“If you are happy to answer the following questions but would like to remain anonymous, just let me know.” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust).

“All your answers will remain anonymous unless you don’t want it to” (Figure 4).

“Bear in mind these are the same questions I have sent to all of my participants and the answers will remain completely anonymous” (Kear, 2020: Interview B).

“All answers will remain anonymous unless you request not to be.” (Kear, 2020: Interview C)

I understand this could have been approached differently with an emailed written confirmation and an information sheet (the same as a face-to-face interview).

Overall, I ended up with three participants (including Erika Lust) out of the twelve I approached. It became nearly impossible to do qualitative research on Feminist Pornography as it is clear this is a private matter for many people that they do not feel comfortable talking about at work. This challenge may be the reason there is a lack of primary research regarding the topic of Pornography and Feminist Pornography from a female perspective.

5 *The Cum shot* – What are the perceptions of female sexuality?

To start off “Sexuality refers to an ensemble of anatomical organs, bodily zones, persons, objects, behaviours, ideas, knowledge, fantasies, sensations, desires and consciousness centred around the genitalia and genital pleasure.” (Jubber, 1991:29). One way of exploring the role of Feminist Pornography would be to look specifically at the effect of Feminist Porn in changing societies perceptions of sex and female sexuality. In this chapter I am looking to understand whether or not it can have an effect once it is compared to evidence from historical to current views of female sexuality, how people respond to Feminist Pornography and how it overall has and can affect women.

Historically women “have been cowed into submission even to the point of co-operating in their own oppression” (Little, 1991:69), the role of the mother and housewife was socially constructed. Sex was a male activity where the women were used to exercise their marital rights. (Redfern & Aune, 2010:50). Sigmond Freud, a sociologist and researcher, who had his private views against women, told the public women who could not orgasm were “suffering from failure to mentally adjust to her ‘natural’ role as a woman” (Jaggar, 1994:482). However, female ejaculation admitted women to psychiatric care because it was described as a “source of disgust” and “abnormal” (Jaggar, 1994:531). Shockingly researchers “denied the existence of female semen” (Jaggar, 1994:530) until the late 1970s and 1980s (Jaggar, 1994:532). In both ways, women’s role was not to gain pleasure in sex; that joy was only for the man.

Although society has progressed significantly, often women still feel ashamed when acting on their sexual desire, Freud’s ideas had a significant impact which women are still navigating to this day. However, this idea is not universal, on the island of Chuuk live an Austronesian-speaking group named The Trukese. Sex is a contest where the man restrains his orgasm until the woman has achieved hers, “if the man ejaculates before his time he is said to have been defeated” (Jaggar, 1994:532). Compared to the penis, the clitoris has one function, pleasure. For men, the penis personifies their masculinity and power; therefore, sexual oppression could be a fearful reaction to the fact that women can achieve orgasm without penetration. With this in mind, it would imply that heterosexuality is no longer absolute; instead, an option. Heterosexuality is eroticised inequality (Rahman & Jackson, 2010:75), leaving women to be “defined sexually in terms of what pleases men” (Jaggar, 1994:481).

Similarly, in modern-day society, instead of hiding female sexuality, it has been used by men to oppress and control women further (Walby, 1990:109). The definition of female identity has become associated with the “possession of a ‘sexy body'” (Redfern & Aune, 2010:102). Society forces women to base their understanding of what women should look like on the hypersexualised versions of women in the media, which has led to many expressing their sexuality through display and exhibitionism (Redfern & Aune, 2010:53). Even schools “brand girls who have sex as ‘sluts'” (Redfern & Aune, 2010:52) and categorised from an early age as either slag or a drag (Walby, 1990:127). Billie Eilish, an eighteen-year-old musical artist with 59.9 million followers on Instagram, has defied societal standards by wearing oversized clothing that does not hug the female form. She argues “If I shed the layers, I am a slut” (Snapes, 2020) which is the saddening truth for many women, they are defined not by talent, intellect or knowledge but instead by how visually appealing their body is to the male gaze. Furthermore, it has led to victim-blaming, for example, the defence used the underwear (a lace thong) in a 2018 rape trial of a 17-year-old girl and the jury settled with a not-guilty verdict. Cases like this convince men and women that “women embody sex, ‘own’ sex and are therefore responsible for it (and for men’s behaviour towards them)” (Redfern & Aune, 2010:53).

To cope with the pressure to maintain ‘sex appeal’, vulnerable, self-hating (Pitts-Taylor, 2007:79), women often seek cosmetic surgery for happiness, fulfilment and confidence. The cosmetic industry is normalised; most celebrities and social media stars have some form of enhancement. Pornography is no longer the primary source of manipulation, convincing young people their natural body is not good enough. An industry once aimed at women older than 40 is now most common amongst women of their “20s and early 30s” (Sawyer, 2020). Some even describe the effect of this as extreme as “hidden adolescent cutting” (Pitts-Taylor, 2007:76) as now more than ever, cosmetic surgery represents sex appeal but also career success.

Where there is oppression, there is also empowerment which has developed the controversial ‘do-me feminist’. This type of feminist recognises how her sexuality uses her and instead gains power in taking advantage of it to “achieve personal and professional objectives and gain control over her life” (Genz & Brabon, 2009:92). This feminist is no different to sex workers and the average woman “fucking their way to broader conceptual horizons” (Potter, 2016). Some argue that sexual freedom is the key to female independence (Genz & Brabon, 2009:91). However, some radical feminists disagree and see the sexually liberated woman resembling the available male fantasy “take-me-now-big-boy fuck-puppet” (Attwood, 2009:102). The do-me feminist is often limited to wanting fantasies about exercising power over men in sex, but many find power in “choosing to let it go” (Lust, 2017). Radical feminists criticise but also misunderstand the concept of the submissive feminist. They fixate on the physical view of a woman being spanked by a man and her crying out in pain but forget this is pleasurable to them. Erika lust argues that in a decade of feminism, society should have progressed to a point where all women can “speak out her true desire” (Lust, 2017) without judgement. The role of Feminist pornography could therefore provide a valuable resource to reassure consumers that their sexual desires are okay and shared by others (Whisnant, 2016:8).

Out of the two interviews, both took different standpoints to the question about sexuality. Interviewee A agreed, while people could access Pornography, then “society will continue to transfer this into real life” (Kear, 2020: Interview A). Similar to the “pornographic reality” (Jagger, 1994:129) where what men see in porn; is then believed as a product of reality. If all visual material can have a direct effect on the public’s perceptions of society, Feminist Pornography could have a chance in changing or even developing a new healthier outlook of sex and therefore making it “easier and more acceptable for women to access erotica” (Redfern & Aune, 2010:70) and their sexuality.

The second interview looked more into the logistics of sustaining an alternative type of Pornography in a billion-dollar industry. They argued that the question regarding people’s visible change in attitudes was “hypothetical” (Kear, 2020: Interview B) and not testable. Their main argument was that Feminist Pornography could become “emasculated” (Kear, 2020: Interview B), no longer associated with feminism and therefore just “another brand of porn” (Kear, 2020: Interview B). However, Feminist Porn has consent, communication, ethical production and fair wages; it is not just “marketed differently” (Kear, 2020: Interview B). They argue if “it is not successful commercially, then feminist porn won’t exist for long” (Kear, 2020: Interview B). Practically this is true, Tristan Taormino (Feminist Porn director) produces her Porn commercially to counteract this problem. When people ask why there is not an abundance of Feminist Pornography; for her, it is ultimately down to a lack of “funding” (Whisnant, 2016:2). She explains how Feminist Porn is a social movement but is also a “genre made for profit” (Kear, 2020: Interview B) much like the interviewee suspects. However, for their assumptions to be correct, there has to be no market for it. Instead, Erika Lust created her films from a bank of anonymous erotic confessions from the public. This project started in 2013 and has since grown into a “global community of people who adore sex and film, and have always hoped for a new kind of erotica” (XConfessions, 2020). This type of growth proves that there is a commercial market for Feminist Pornography, which the interviewee agrees “would probably contribute to further changes in social attitudes to sex and sexuality” (Kear, 2020: Interview B).

6 Feminist Pornography – Agree or disagree?

Radical anti-porn feminists argue that the best strategy to end the objectification of women in pornography is through criminalising and attempting to eliminate it but is this an effective strategy or are their ideas privileged and “misguided” (Saul, 2003:102)? As the researcher I will explore the views of Anti-porn feminists and why Feminist Pornography may be a positive solution to the adverse effects of mass-produced mainstream Pornography.

Anti-porn feminists claim to be feminists, fighting for the rights for ‘all’ women. However, by assuming women are only the victims in Pornography, they are disregarding women who have chosen to work there. Feminism includes the choice over one’s own body but also the fight against patriarchal control. By only viewing women as the victim and in need of rescue, feminists are contradicting their core values of overturning the patriarchal ideology. Some anti-porn feminists argue there is no such thing as sexual freedom in Porn, mockingly Douglas says “if forced to choose between freedom and sexuality, any feminist worth her salt would not choose sex” (Douglas, 1983:14). Some say we must look at societal values and “reexamine the priority of libertarianism over doing damage to women (and calling it erotic)” (Freidman, 1979:3) suggesting a strategy like an increase in production of Feminist Pornography would be ineffective. However, Judith Butler (2008) suggests reducing the stigma and shame attached to watching and producing Porn would mean there would be a growth in independent erotic cinema, like Feminist Porn. Over time it would give less attention to the free sites naturally giving them less power and control in the industry. The best strategies to reduce the use of Pornography would be “lobbying for better sex education in schools” (Saul, 1968:91) to tackle the root cause of Porn traffic. Most young people look at Pornography out of curiosity to identify and satisfy tastes and cravings (Levy, 2005:185) about sex. It would also be essential to force society to have better social attitudes to sex and sex work and support those who are creating ethical Pornography without judgement (Saul, 2003:91).

In some ways, the thought that criminalising Pornography will eliminate gender equality in society is foolish. Some argue this thought is a “comforting placebo” (Saul, 2003:101) because it is something physical to focus energy on. It is a distraction away from the real issue, which is the institutions within society that is causing the ingrained inequality. For example, in Morrocco, it is illegal to produce or watch Pornography, but this does not mean it is free from inequality, 64% of women (15-49) think that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances (Unicef, 2011:8). This blanket censorship of Pornography not only displaces and re-routes the violence it seeks to forestall (Gillis & Howie & Mumford, 2007:256) but also increases the stigma against the industry.

By banning pornography, it would immediately become “illicit property” (Kear, 2020: Interview A) following other deviant behaviours like drugs and sex work into the hands of criminals, gangs and people willing to break the law. Now illegal, the companies producing Porn no longer would need to comply with the Government’s health and safety standards and regulations, meaning an increased risk of danger for those involved. There could also be more violence against women to comply with the scene, and they could even withhold wages.

The treatment of women in Pornography cannot be argued against, as currently much mass-produced mainstream Pornography is degrading and could qualify as “a form of hate speech” (Butler, 2008:129). Some Pornography is non-consensual, and it is disturbing how little people are aware of this. With human trafficking and modern slavery “increased by more than 50% in a year” (Grierson, 2020), the likelihood that commonly viewed Porn contains coercion, abuse and manipulation is high. However, the reasons why trafficking is prominent in Porn is because there is a market need for it. With “35% of all internet downloads” (Culture Reframed, 2020) being Porn, traffickers are merely profiting from the demand for Pornography. If it becomes illegal, this will only ever increase, creating a more substantial demand for transnational organised crime, making more women vulnerable to danger and violence. Another reason why this could negatively impact women is the loss of jobs and wages if it becomes illegal. The loss of a job would push women further into poverty which is usually why most women choose sex work in the first place.

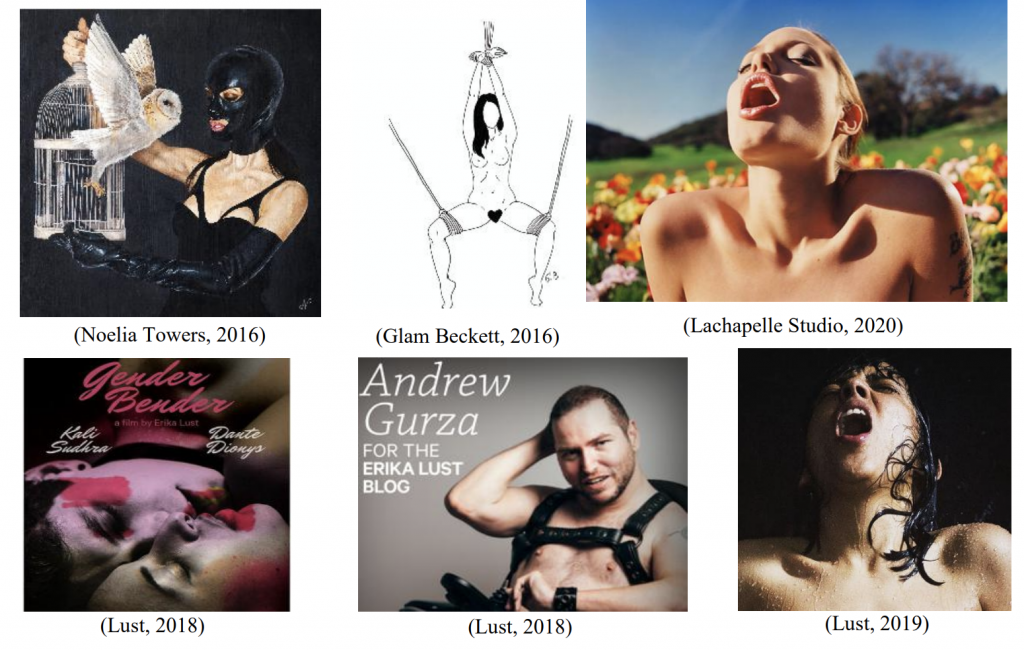

The imagery and anecdotes used in the anti-porn campaigns have a focus on violence against women, often taken from the S&M genre of Porn, it can be argued anti-porn activists generalise their assumptions with “flimzy” (Assiter & Carol, 1993:18) evidence that is not representative of the entire community. One of the anecdotes used in a Women against Pornography (WAP) campaign is of Linda Marchiano who was coerced into Porn, assaulted and then raped. This particular story was used to argue against pornography “in general” (Saul, 2003:97). The images and stories act as an effective marketing strategy enraging the public, creating a moral panic which builds attention to their campaign. The evidence generalises the assumption that viewing Porn makes men more likely to commit rape. Women are prettified and emotionless, which arguably makes “rape more difficult to perceive as rape” (Saul, 2003:102). Fantasy and reality cross over when watching pornography, suggesting this “sexualised inequality must carry over into other areas of life” (Saul, 2003:105). The issue with Pornography causing rape myths may have some truth, but some argue it cannot be generalised to include all genres of Porn because “most men are not aroused by violent pornography, instead they are disgusted” (Saul, 2003:106). It is unlikely that legislative action on Pornography can solve the issue of Rape myths as a whole. In the past, when given the right to censor free speech, The Government has instead restricted other resources like contraception, positive sexuality discussions and safe sex education (Saul, 2003:92). There is also a risk of endorsing essentialist ideas of all men becoming inherently sexually predatory (Jagger, 1994:138).

The imagery from the S&M genre can increase the stigma against BDSM practices which is a community that claims to be “the most consensual sexual community around” (Saul, 2003:105). In the 2019 Porn Hub review, a website that has billions of visits per year, the top 10 genres that were most popular only included one BDSM feature. At number 10 was a practice called “Femdom” (Porn Hub, 2019) which is a form of play where the woman is the dominant and her submissive is male, this switch in gender roles contradicts anti-porn critical views that the average male viewer is guilty of watching Pornography that violently objectifies women.

Leading anti-porn activist Catharine Mckinnon argues the increased input of Pornography has created a “pornographic reality” (Jagger, 1994:129). Hypersexualisation of men and women in advertisements and the media, desensitising us from explicit and graphic nudity and immunity to violence. Pornography has arguably set “the standard for female sexuality” (Jagger, 1994:152)and beauty as women base their self-worth on their sex appeal. In straight culture young men watch pornography and base their ideal partner on what they see on screen, these unrealistic expectations on women not only ignore the focus and importance of female sexuality but also the increased pressure leads to lower self-esteem. These “fake versions” (Jagger, 1994:152) of people are clones of the popular child’s toys, Barbie and Ken dolls: hairless and supersized appendages. Although Feminist Pornography still is graphic, their Pornography is more relatable. There is an equal focus on climax and the people having sex are body positive and inclusive, making sex on screen relatable rather than setting unattainable standards.

Overall, Pornography is a vast industry, and Feminist Pornography is a small, almost insignificant part of it. Every industry has companies that focus more on profit over people’s livelihoods, this is inevitable. However, to make a dent in this issue using legislative force has more negative effects than positive. Feminist Pornography could arguably be seen as a privileged idea as well, as those involved choose to do it through the opportunity for sexual self-expression and not necessarily desperation. Furthermore, the generalisation of evidence from radical feminist campaigners is “misguided” (Saul, 2003:102) as it comes from anger and not from rationality. One effective strategy which reaffirms the positive role of Feminist Pornography would be to switch roles with those in power. Adding more women to the production process (writing, directing and producing) will create a female gaze and a safer environment for the performers.

7 Afemale behind the lens – Does this change the gaze?

The main difference between mass-produced mainstream Pornography and Feminist Pornography is that instead of being the object of the gaze, women are behind the lens of the camera.

I asked Erika Lust about the importance of Feminist Pornography, and one of her points was to ensure women were not “represented solely as objects for male pleasure” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust) and instead make sure “women are behind the camera and making active decisions about how the film is produced and presented. That means having women in leading roles as directors, producers, art directors, directors of photography etc. So the stories are told through the female gaze” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust). One of her female guest directors produced a film called ‘Coffee with Pleasure’, one of the female performers in this film explained how she felt having a mostly female crew on set, she said, “I have never shared set with more than two males, and I think it’s very interesting how you can feel because they are not in control, so it’s more females that are in control, and nobodies up and nobodies down, we are on the same level” (Lust, 2019). Here, she explains how a female director makes her feel equal and comfortable. Moreover, even with males onset, the perspective remains female.

The gaze was created around the mid 19th century when the female body first started to be fetishised. Sex workers who were commodities walked the streets alone at a time when women walking alone was unheard of, they dressed in clothing that eroticised the female form to attract customers. Lower class women also walked the streets to get to work; as a result, all of these women became commodified to men (Stratton, 1996:90). “In the surveillance order organised by the modern state, in which the patriarchal state itself was at the pinnacle, men could watch women” (Stratton, 1996:96) however women could not gaze at men, this was a violation of social and moral boundaries and made them deviant and as a result only a “passive object of male desire” (Stratton, 1996:96). From this came the invention of photography which formed the “surveillance of the female body” (Stratton, 1996:107).

Laura Mulvey coined the phrase ‘The Male Gaze’ in 1975 in her essay Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure. She draws on the work of Freud and his perception of scopophilia, Mulvey feels it is one of the pleasures of film. However, Freud “associated scopophilia with taking other people as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze” (Mulvey, 1975:8). Formerly, the pleasure associated with looking is from the “conditions of screening” (Mulvey, 1975:9), if the person is watching from a cinema or alone in the house, it gives “the spectator an illusion of looking in on a private world” (Mulvey, 1975:9). This idea can relate to the shame attached to Pornography, in my interviews, some showed signs of embarrassment around the topic, and it could be because they are under the illusion it is private (Mulvey, 1975:9) and they are unaware of the scale of people sharing the experience. Mulvey states two contradictory aspects of the pleasures of the gaze. The first of “scopophilic, arises from pleasure in using another person as an object of sexual stimulation through sight” (Mulvey, 1975:10) which directly relates to the pleasures people get from voyeurism in sex and watching pornography. The second “developed through narcissism and the constitution of the ego, comes from identification with the image seen” (Mulvey, 1975:10) which in layman’s terms means the pleasure that comes from holding the gaze develops through an obsession with the self and their fantasies and reflections.

The gaze is discussed theoretically in both art and cinema, in European art, the nude woman is often looking out of the painting. The gaze that she is seducing with her naked body is assumed, male. As John Berger explains “she is not naked as she is, she is naked as the spectator sees her” (Berger, 2008:44) therefore suggesting her body is not her own instead it is a “spectacle” (Stratton, 1996:109) of male desire and affection. Women are not only watched through the camera lens, but it is also through the media and to be gazed continuously at on the street. The male gaze sees women like they are an animal in a circus, to not just be visible, but also experienced and displayed (Stratton, 1996:109) like a trophy. But women are not just watched by others, they are also constructed to survey themselves. This is similar to Michel Foucault who described the increased social control of society developing from bio-power. He suggests individuals “voluntarily control themselves by self-imposing conformity to cultural norms through self-surveillance and self-disciplinary practices” (Pylypa, 1998:22) meaning people have a desire to conform to what society says is normal and therefore end up surveying themselves. Female director Jill Solloway argues women “don’t write culture, we are written by it” (TIFF Talks, 2016), women are therefore constructed to survey themselves and as a result, become an object of their gaze and the gaze of others. Another reason why women are limited to the object and men are the ones holding the gaze is that “we don’t learn to see beauty in men’ that men are never even placed in that category” (Redfern & Aune, 2010:69).

The female gaze is not merely the opposite of the male gaze, to objectify men for the pleasure of the woman; instead, it is a new perspective and outlook altogether. As spoken about previously, Lust’s films see the female gaze as the woman regaining control in such a saturated male industry. “The female body and sexuality is rarely seen as her own” (TEDx Talks, 2019) and therefore it could be argued a film with a female director would prioritise the woman’s body as only hers. The female gaze uses the camera to show the audience “how it feels to be the object of the gaze” (TIFF Talks, 2016), focusing energy on the feeling behind it rather than just what is being seen objectively. Jill Solloway speaks openly about the female gaze as a “subjective camera” (TIFF Talks, 2016), through the camera she is telling the audience “I’m not showing you this thing, I want you to feel it with me” (TIFF Talks, 2016). It is important to recognise the female gaze as this creates “stepping stones to more than just access to quality erotica for women, but also to a healthier and happier sexual self-expression for men” (Redfern & Aune, 2010:69).

The question is if a woman is behind the lens, does this change the gaze? My answer is not necessarily as the female photographer Lone Mørch explained “our gaze is never without power, it is never neutral, it is informed by our experiences and conditioning. Our biases and our beliefs, our preferences and agendas, and also how we feel and see about ourselves” (TEDx Talks, 2019). This suggests the gaze of the person watching is not dependent on gender, instead it is social construction. We are conditioned to conform to roles, women are nurturing and thought-provoking, men are objective and logical. This has transferred into who holds the gaze and why a female perspective may be refreshing. Not all male directors have the same values, in the film, Carol, the male director Todd Haynes focused his research around underground female photographers of the ’50s which Cate Blanchet therefore felt was a “very female gaze he was using in the piece” (Vanity Fair, 2016). So the real question is not about whether the gaze is changed by gender but instead does your gaze as the reader limit or liberate the one you are watching?

8 Findings and Discussion

Introduction

In the research, I set out to explore the role of Feminist Pornography in society. I asked the opinion of someone on the front-line, a female director but also the opinions of academics who could provide a theoretical response to the topic. The three areas of focus were the female gaze, the impact of Feminist Pornography on social attitudes of female sexuality and to understand comparative views of activists and why they had those opinions. The nature of qualitative email interviews was essential to capture the honest opinions of a seemingly sensitive topic through feminist research. I conducted the research through email because of time and geographical restraint. The findings will be displayed thematically under five headings. To see the email’s that I sent for reference, please refer to the appendices at the end of the dissertation.

Presentation of Data

I used Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method to isolate and analyse critical themes in this chapter. The four themes chosen provide direct and indirect responses to the role of Feminist Pornography. Raw data gathered over email form the base for the themes which were explicitly chosen for their relevance to the main question.

Pornography as shameful

I found it challenging to recruit academic participants because of the topic of Pornography. In reference to my methodology page 15, Pornography is seen as a taboo subject and is associated with the “extreme and violent scenes that are available in abundance on the free tube sites” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust). This idea has meant fewer people were willing to take part because of embarrassment and shame associated with Porn, especially in the workplace. Furthermore, this association may be due to the lack of knowledge surrounding the topic of Feminist Pornography which I found for both academic participants and emphasises the need for more research be done in this area. The role of Feminist Pornography is to create erotica that has positive connotations to reduce judgement, shame and insecurity and encourage sexual expression and like Lust said in the interview to show “the importance of representing women with their own sex drive and desires” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust). If more academics knew about this, then maybe the recruitment process would not have been as complicated.

Creating a safe space

One of the aims of Feminist Pornography is to create a safe space for performers to work. The participants highlight multiple contributing factors. The first example of this topic was from the female director, Erika Lust. She gave a detailed description of how the production process ensures a safe and secure environment for the performers to work and express themselves freely without judgement and insecurity.

“Everything about the sex scene is discussed in advance and agreed-upon with the performers in the pre-production process. They tell us their boundaries, the type of sex that they like to have, what they would like to try, what they don’t like to do during sex, who they want to work with, who they don’t want to work with… Everything in the sex scene comes from the performers” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust).

“Once the sex acts are discussed and agreed upon it’s important that there aren’t last minute changes that could make a performer feel coerced into doing something” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust).

As someone working directly in the industry and a contributor to ensuring safe space, the information Erika Lust provided was valuable in understanding the difference in work environments between feminist and mainstream Pornography. However, these standards should be universal to all. In Feminist Pornography, the performers have the upper hand, and the director is not there to direct but instead capture the scenes, this ensures a more authentic representation of sex to the viewers watching. One particularly thought-provoking word was “coerced” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust), Porn is often associated with manipulation and coercion of women especially. Therefore it is crucial that Lust has recognised this and has made moves to change this and create a safer space in Porn.

Furthermore, the dangers of criminalising Pornography showcase the importance of Feminist Pornography to ensure a safe space at work. Here the academic participant was responding to the question about whether criminalising and attempting to eliminate Pornography would be the most effective option in tackling the degrading nature of mass-produced mainstream Porn.

“As soon as anything is banned it becomes illicit property. Pushing pornography underground would reduce the safety of the participants. It could also direct the female participants in to other risky situations in the need to find a wage” (Kear, 2020: Interview A).

Interview A highlights the risk of pushing Pornography into the hands of gangs and traffickers, as mentioned in chapter 2, page 23, human trafficking and modern slavery “increased by more than 50% in a year” (Grierson, 2020). Porn is transnational therefore criminalising it would only ever increase the market need for it illegally. Without the choice to return to a ‘normal’ job, those remaining in the industry would be a victim to further coercion and abuse. The criminalisation of sex work would leave a lot of people unemployed and this desperation is noted in her response. They may have chosen sex work for its flexibility around childcare or because they were lacking in educational qualifications. Through unemployment, it may force them into continuing to work in sex work but risk getting a criminal record. The role of Feminist Pornography is to create a safe space and solution to this issue.

The definition of Feminist Porn

There is a difference in opinion when it comes to what defines Feminist Pornography. In my opinion, it is a term that is empowering because pro-sex feminists have reclaimed a once derogatory word associated with negativity and objectification and have transformed it into something empowering and informative. However, to my surprise, Lust disagreed.

“I don’t really like to refer to my work as ‘feminist porn’ now because the term has become a very general label for anything that is made by a woman and it has lost some meaning. Women are considered a niche, so we are labelled ‘feminist porn’, ‘ethical porn’ or ‘porn for women’, reinforcing the idea that we are not really ‘porn’.” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust).

The fact that women are forced into a genre that does not represent the whole industry is similar to chapter 1, page 18 where historically women “have been cowed into submission” (Little, 1991:69). This leaves women in a role that lacks control and impact. Furthermore, Interview B is sceptical about Feminist Pornography, he exclaims “If it does not trade in cliches, how will the viewer recognise feminist porn as porn?” (Kear, 2020: Interview B). This idea comes from the fact that Pornography has negative connotations, and this has been generalised to represent all Porn. Feminist Pornography, in my opinion, is a term used to challenge stereotypes and cliches within the Porn industry and this is why Feminist Pornography or erotica as use of a better term, has a positive impact and role on society.

Feminist Porn and sexuality

Another topic raised in the research was the impact of Feminist Porn or mainstream Porn on social attitudes regarding sex and sexuality. As discussed in chapter 1, page 20, Interview A agreed that any Porn could transfer into real life. This idea suggests that if mainstream Pornography can transfer, there is a chance Feminist Porn can have an equal impact on developing new attitudes to sex. Lust argued the social attitudes were dependant on the access and “increased availability” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust) of Pornography. In order for Feminist Pornography to maintain it’s value’s, most films require you to pay. This provides peace of mind to the viewers as they know the performers are paid fairly. However, the reason why Porn has had adverse effects on society and created a “pornographic reality” (Jagger, 1994:129) is due to people not wanting to pay for their pleasure. Furthering this, Interview B argued that Feminist Pornography could only continue to grow if it became commercially successful. Although society can benefit from a better representation of female sexuality and sex, it seems the possibility of it contending with the monstrously big Porn industry as a whole is unlikely.

The Female Perspective

Feminist Pornography is feminist because it seeks to provide a better representation of female sexuality through the eyes of a female director and producer. It has since grown to incorporate many other factors, but this was the original social movement. The participants were asked whether or not the female gaze was any different to the male gaze that is currently ruling the porn industry. Both Interview A and Erika Lust agree that a female perspective is different and therefore better at producing Porn that is “more appreciative of women” (Kear, 2020: Interview A) with “female sexuality and pleasure at the forefront” (Kear, 2020: Interview with Erika Lust). However, as discussed in chapter 3, page 28, the type of Porn created is not dependant on gender but instead on the directors “experiences and conditioning” (TEDx Talks, 2019). It is about the act of feeling the scene, rather than just viewing it; if this is portrayed well, it can create more intimacy and authenticity.

9 Conclusion

Overall, I agree there is a role for Feminist Pornography in society. However, there are contributing factors that significantly limit the impact and benefit it could have. If more people admitted Porn is the new sex education and people became better informed of the benefits of Feminist Pornography, then there may be a chance of it shifting the shame attached to Porn, sex and female sexuality.

Qualitative methods of research are useful in receiving in-depth honest answers. However, the academics that I interviewed had limited to no knowledge of Feminist Pornography as a topic and therefore provided answers that were not relevant or useful in answering the main research question. In the future, if I were to repeat the research, I would purposefully be selective and interview those who specialised in gender and sexuality. Another limitation was the consent issue in Email interviewing; this form of research also negatively affected the recruitment of participants. If I were to use this method again, I would take care to make sure the participants electronically signed a consent form before starting.

The topic of Feminist Pornography has many avenues that are still in need of being explored, furthering the research; I would like to do a combination of participatory research in the form of observations and in person qualitative interviews. I want to interview a range of people on the set of a Feminist Porn scene, that way I can gain a perspective from all parties involved and gain an insight into the experiences and environment of those working. This project would carry over for an extended period, observing the entire filming of one Porn short film.

Another further research that would delve deeper into the effects of Feminist Pornography on social attitudes in society would be a psychological study to compare the change in female self-esteem with watching mass-produced mainstream Porn versus Feminist Pornography.

Bibliography

Assiter, A. & Carol, A. (1993) Bad Girls and Dirty Pictures. London: Pluto Press.

Attwood, F. (2009) Mainstreaming Sex: The Sexualisation of Western Culture. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

Banks, O. (1986) Becoming a Feminist: The social origins of ‘first wave’ Feminism. Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books.

Clarke, V. and Braun, V. (2006). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), pp.297-298.

Breslaw, A. (2013) So, What Is Feminist Porn? Find Out From a Woman Who Makes It. Cosmopolitan, 6 November. Available Online: https://www.cosmopolitan.com/sex-love/news/a16343/tristan-taormino-feminist-porn-interview/ [Accessed 07/04/2020].

Cochrane, K. (2013) Feminism: The fourth wave of feminism: meet the rebel women. The Guardian, 10 December [Online]. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/10/fourth-wave-feminism-rebel-women [Accessed 11/03/2020].

Crochet Caché (2020) Dessin 148 [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.instagram.com/p/B9Wr1dQB3oh/ [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Culture Reframed. (2020) Culture Reframed: Building Resilience & Resistence to Hypersexualised Media and Porn. Available Online: https://www.culturereframed.org/ [Accessed 29/03/2020].

Douglas, C. A. (1983) Pornography: Liberation or Oppression? Off Our Backs, 5(13). Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25793966 [Accessed 12-01-2020].

Emerson, C. (1975) Revolutionary feminism: A history of women’s liberation and revolution. Michigan: Sun Press

Friedman, D. (1979) Feminist Perspectives On Pornography. Off Our Backs, 1(9). Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25792864 [Accessed 11-01-2020].

Genz, S. & Brabon, B. A. (2009) Do-Me Feminism and Raunch Culture. Postfeminism, 91-105. Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09z88.8 [Accessed 04/04/2020].

Gilmore, D. D. (2001) Misogyny: The Male Malady. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gillis, S. & Howie, G. & Munford, R. (2007) Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Glam Beckett (2016) Woman in bondage [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BJur34JAb9x/ [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Grierson, J. (2020) UK police record 51% rise in modern slavery offences in a year. The Guardian, 26 March [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/26/uk-police-record-51-rise-in-modern-slavery-offences-in-a-year [Accessed 29/03/2020].

Hesse-Biber, S. N & Leavy, P. L. (2007) Feminist Research Practice. London: Sage Publishing.

Jagger, A. M. (1994) Living With Contradictions: Controversies in Feminist Social Ethics. Colorado: Westview Press Inc.

Jubber, K. (1991) The Socialization of Human Sexuality. South African Sociological Review, 4(1), 27-49, October. Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44461248 [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Kaur, R. & Nagaich, S. (2019) Understanding Feminist Research Methodology in Social Sciences. Available Online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3392500[Accessed 07/04/2020].

Kear, G. (2020) University Dissertation [Email]. Message sent to E. Lust (erikalust@gmail.com). 10 February 2020, 13.39.

Kear, G. (2020) Feminist Pornography Questions [Email]. Message sent to Interview B. 24 February 2020, 08.48.

Kear, G. (2020) University Dissertation on the topic of Feminist Pornography [Email]. Message sent to Interview A. 14 February 2020, 12.31.

Kear, G. (2020) University Dissertation on the topic of Feminist Pornography [Email]. Message sent to 12 participants. 10 February 2020, 14.24.

Kear, G. (2020) Questions about the GEMMA programme and gender dissertation research questions on Feminist Pornography [Email]. Message sent to Interview C. 14 February 2020, 13.17.

Lachapelle Studio. (2020) Portraits: Angelina Jolie. Available online: http://www.lachapellestudio.com/portraits/angelina-jolie [Accessed 07/04/2020].

Levy, A. (2005) Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and The Rise of Raunch Culture. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd.

Little, M. B. (1991) THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE CHURCH AND SOCIETY. Caribbean Quarterly: The Social Teaching of the Church in the Caribbean, 37(1), 68-82. Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23050552 [Accessed 05-04-2020].

Lust, E. (2017) Feminist and Submissive Trailer [Video]. Available Online: https://xconfessions.com/film/feminist-and-submissive [Accessed 03/04/2020].

Lust, E. (2018) Gender Bender [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BkShhTzlewo/ [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Lust, E. (2018) Getting wet all over… [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.instagram.com/p/BiekKdel8_s/ [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Lust, E. (2019) The making of Coffee With Pleasure [Video]. Available Online: https://xconfessions.com/film/coffee-with-pleasure [Accessed 11/04/2020].

Lust, E. (2019) Values. Available Online: https://erikalust.com/values/ [Accessed 07/04/2020].

Lust, E. (2019) Getting off as a Gimp: Masturbation and Disability [Photograph]. Available Online: https://erikalust.com/getting-off-gimp-masturbation-disability/ [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Mulvey, L. (1975) Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Screen, 16(3), Autumn, 01 October, 6–18. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6 [Accessed 11/04/2020].

Noelia Towers (2016) The Releaser [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.noeliatowers.com/?lightbox=dataItem-jxnx7hg1 [Accessed 16/04/2020].

1933, ‘Erotica’, Oxford English Dictionary: The definitive record of the English language (OED), Oxford University Press, viewed 5 March 2020, < https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/64084?redirectedFrom=erotica#eid>.

1891, ’Erotic’, Oxford English Dictionary: The definitive record of the English language, Oxford University Press, viewed 5 March 2020, < https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/64083?redirectedFrom=erotic+&>.

Pachu M Torres (1985) Vodevil [Photograph]. Available Online: http://www.pachumtorres.com/product/vodevil [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Parliament.uk. (1989) Living Heritage: Women and the Vote: Women get the vote. Available Online: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/thevote/ [Accessed 11/03/2020].

Pitts-Taylor, V. (2007) Miss World, Ms. Ugly: Feminist Debates. Surgery Junkies: Wellness and Pathology in Cosmetic Culture, 73-99. Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hjd3s.7?refreqid=excelsior%3A84c42b270e9898107ee2e7f9aa3b6592&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents [Accessed 04/04/2020].

Porn hub. (2019) Porn hub Insights: The 2019 Year in Review. Available online: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2019-year-in-review [Accessed 05/03/2020]

Porn Hub. (2020) Very sexy midget. Available online: https://www.pornhub.com/view_video.php?viewkey=ph5de4c247b3e03 [Accessed 07/04/2020].

Porn Hub. (2017) Hot chubby girl fuck and facial. Available online: https://www.pornhub.com/view_video.php?viewkey=ph588a09046a31a [Accessed 07/04/2020].

Potter, C. (2016) Not Safe for Work: Why Feminist Pornography Matters. Dissent Magazine, Spring 2016 [Online]. Available Online: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/not-safe-for-work-feminist-pornography-matters-sex-wars [Accessed 04/04/2020].

Pylypa, J. (1998) Power and Bodily Practice: Applying the Work of Foucault to an Anthropology of the Body. The University of Arizona, vol 13, 21-36. Available online: https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/arizanthro/article/view/18504 [Accessed 11/04/2020].

Rahman, M. & Jackson, S. (2010) Gender & Sexuality: Sociological Approaches. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Randall, R. S. (1989) Freedom and taboo: pornography and the politics of a self-divided. London: University of California Press.

Redfern, C. & Aune, K. (2010) Reclaiming the F Word: The New Feminist Movement. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Reinharz, S. (1992) Feminist Methods in Social Research. New York: Oxford University Press.

Roberto Losada (2016) El Aquelarre [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.behance.net/gallery/37559119/El-Aquelarre [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Ryberg, I. & Mulvey, L. & Rogers, A. (2015) Imagining Safe Space in Feminist Pornography. Diversity, Difference and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures. Available Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16d6996.11 [Accessed 11-01-2020].

Saul, J. M. (2003) Feminism: Issues & Arguments. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sawyer, M. (2020) ‘I’d rather spend £300 on fillers than face cream’: the rise of face tweakment. The Guardian, 25 January [online]. Available Online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/jan/25/rather-spend-300-fillers-rise-tweakment-face [Accessed 04/04/2020].

Snapes, L. (2020) ‘If I shed the layers, I am a slut’: Billie Eilish addresses body image criticism. The Guardian, 10 March [online]. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/mar/10/if-i-shed-the-layers-i-am-a-slut-billie-eilish-addresses-body-image-criticism [Accessed 04/04/2020].

Stratton, J. (1996) The Desirable Body. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Tantalizing Sensation (2018) Pull my hair! [Photograph]. Available Online: https://www.instagram.com/p/Bju6rD-gvWu/ [Accessed 16/04/2020].

TEDx Talks. (2019) The power of the gaze,What I learned from photographing a 1000 naked women | Lone Mørch | TEDxAarhus [Video]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fK2GxMePoe0 [Accessed 11/04/2020].

TIFF Talks. (2016) Jill Soloway on The Female Gaze | MASTER CLASS | TIFF 2016 [Video]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnBvppooD9I [Accessed 11/04/2020].

Türkis (2020) Woman standing holding her breast with hand behind back [Photograph]. Available Online: https://xconfessions.com/collaborators/artist-gallery/turkis [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Unicef (2011) MOROCCO MENA Gender Equality Profile: Status of Girls and Women in the Middle East and North Africa (October 2011). Available Online: https://www.unicef.org/gender/files/Morroco-Gender-Eqaulity-Profile-2011.pdf [Accessed: 29/03/2020].

Vanity Fair. (2016) Cate Blanchett on the Female Gaze In “Carol” [Video]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYgzL28Bbgs [Accessed 11/04/2020].

Vinz Free (2020) Vinz Free Porn Performer [Photograph]. Available Online: https://xconfessions.com/collaborators/artist-gallery/vinz-free [Accessed 16/04/2020].

Walby, S. (1990) Theorizing Patriarchy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Whisnant, R. (2016) “But What About Feminist Porn?”: Examining the Work of Tristan Taormino. Sexualization, Media & Society, 1-12. Available Online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2374623816631727 [Accessed 04/04/2020].

XConfessions. (2020) About. XConfessions by You & ErikaLust [Online]. Available Online: https://xconfessions.com/about-xconfessions [Accessed 04/04/2020].