Abstract

Central to the ability of activist organisations success in creating change is the way in which they frame the debate. This rhetorical period is the focus of this dissertation, which implements an instrumental case study to explore ‘collective action framing’ theory. The purpose is to examine whether this theoretical framework provides an effective analysis of the reasons behind the success of social change, or rather, the mechanisms with which this change is reached. The activist organisation used in this case study is Stop Funding Hate. Their aim is to change the use of sensational, anti-migrant and hateful language used in tabloid journalism.

Author: Frazer David Guy, May 2019

BA (Hons) Sociology and Anthropology with Gender Studies

List of Figures

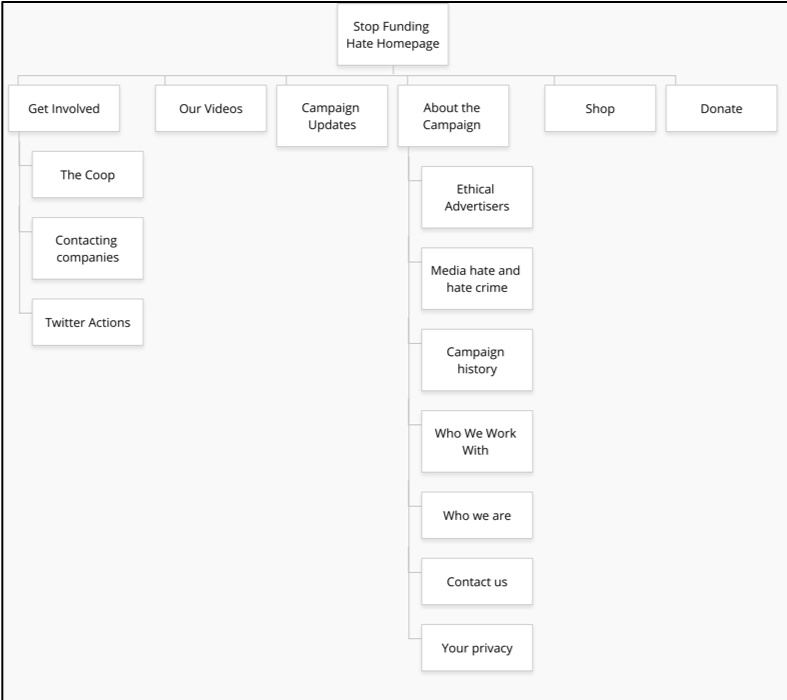

- Figure 1: Stop Funding Hate site map

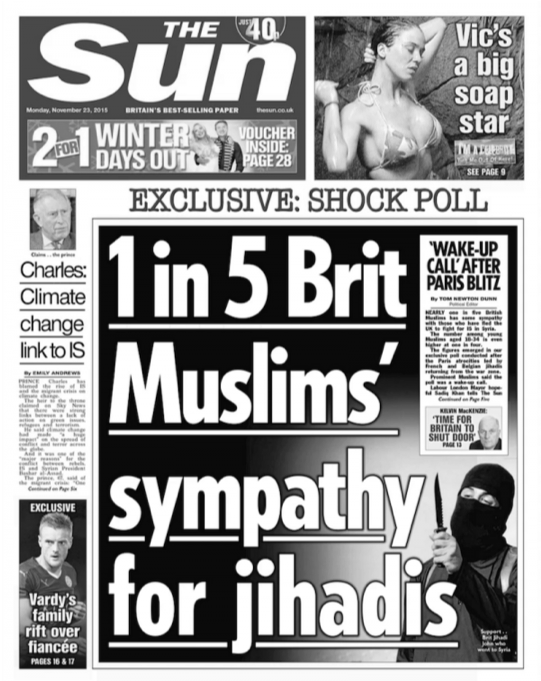

- Figure 2: “‘1 in 5 Brit Muslims’ sympathy for jihadis” headline

Table of Contents

1 Introduction

Activism is no longer solely acted upon in the physical world, as we now have access to the internet. The internet allows communication to travel across the globe, forming a new platform for global cultural information (Fulcher and Scott, 2011, p. 356). This is labelled as ‘cyberspace’ in the literature, described by Gauntlett as “the conceptual space where computer networking hardware, network software and users converge” (2000, p. 220). McCaughey and Ayers note that the internet has undergone a process of commercialisation, which demands both a scholarly and political response (2003, p. 1). A part of the political response to this change in cyberspace is the development of activism online, which McCaughey and Ayers describe as ‘cyberactivism’ (2003, p. 1). An early example of cyberactivism is given to us by Fulcher and Scott, who describe the ‘Battle for Seattle’ in 1999 (2011, p. 634). This event was organised by environmental factions online, which for one of the first times in activism history, allowed the seamless coordination of international acts of protest. While this demonstration took place in Seattle, the online groups which organised it coordinated with those around the world: including in Edinburgh, Scotland (2011, p. 634).

This emerging field of study is already broad, yet most of the literature has a focus on issues that were a matter of protest before cyberspace. The protests in Seattle and Edinburgh were environmental based, while others focus on financial issues such as the world bank (and other international bodies of finance) protests of 2001 onwards (Vegh, 2003, p. 86). This dissertation takes an organisation that campaigns for a reduction in anti-migrant and hateful journalism. This particularly applies to the space afforded to traditionally paper-based news sources, who have progressed to a digital presence online. Stop Funding Hate aims to make this form of journalism economically disincentivised, by targeting their efforts, not at the creators of the content but their financial backers: their advertisers. Stop Funding Hate aims to draw a juxtaposition between the content displayed on these sites and the corporate social values. In doing so, they hope to persuade advertisers to withdraw support from these newspapers and directly make the printing of stories unviable economically. The focus of this campaign is on the online news sites of these newspapers and therefore is one example of cyberspace activism that is connected to the internet and not an extension of activism that exists outside of this cyberspace.

While this

dissertation explores Stop Funding Hate through the form of a case study, the

primary purpose is the application of a theory that has grown in prominence in

the study of social movements. This theory is collective action frames, based

upon the initial ideas of Goffman (1974) but developed by various writers. The

case study will therefore follow the instrumental framework as outlined by

Pamela and Susan (2008,

p. 548-549). This instrumental framework seeks to examine a theoretical idea or

concept and tests its application in research. In this instance, I use the case

study of Stop Funding Hate to examine test collective action framing as a tool

of analysis. This framework is explored in detail in the third chapter,

methodology.

2 Literature Review

In this literature review I will give a historical and contemporary account of the theoretical understandings of social movements, noting the key points in the progression of this field of study. This will provide a background to the development of ‘collective action framing’, the theoretical framework central to my dissertation. I will then conceptualise collective action framing and outline its applications in the study of social movement research. Finally, I will explore the literature on online activism. In examining these areas, I will contextualise the focus of my case study: the organisation ‘Stop Funding Hate’. In contextualising Stop Funding Hate, I will form a theoretical basis for the understanding of the social justice causes they campaign for. The methods used by this group and others like it will be explored in this section too. This contextualisation will enable me to fully understand the aims and objectives of Stop Funding Hate and set the basis for the application of collective action framing as a tool of analysis in the following chapters.

Historical understandings of social change

Smelser provides an early attempt at understanding social change in his ‘Theory of Collective Behavior’ (1962). Smelser breaks down these changes into phases. The first is that of a structural strain, where individuals within a given social group come to the decision that something is wrong. The second phase is a development of this feeling, to that of a belief which then leads to action on the issue. Eventually, although not in all cases, a social movement forces capitulation and change is achieved. It should be noted that this change does not always reflect the aspirations of those initial activists. Anecdotally, this could be seen ingiven examples of climate change protest. These protests have been ongoing for decades, yet global temperatures are still rising. Progress has been made, but not always to the ambition of the activists.Smelser’s theory is reminiscent of Griffin, who identifies three periods of change in historical social movements. The first is that of a period of inception, then a period of rhetorical crisis and a period of consummation (Griffin in Atkinson, 2017, p. 25). The connection between these two theories is clear, with the periods of inception linking to that of structural strain. The rhetorical crisis is present in the social movement’s early efforts to develop the belief that leads to action. The period of consummation entails the activities of the social movement in full swing, which may extend to its completion or carry on beyond this point. The point of completion in a social movement is not always present, and even if it reaches its initial aims alternative issues may present themselves. Smelser and Griffin place great significance on the actions of individuals in the formation of social movements, as the periods of inception and structural strain both revolve around the individual realisation of a need for change. Atkinson labels these theories as a “meaning-oriented”, as they focus on the reasons behind the actions of collective behaviour (2017, p. 25).

Social movement theory progressed because of the wide-ranging effects of the movements present in the 1960s, with particular concern for the American landscape (Jenkins, 1983, p. 528). This resulted in a new dominant understanding of how social movements operations, namely in ‘resource mobilisation theory’. Resource mobilisation theory directly connects the success of a social change organisation on the resources at its disposal. It argues that actions taken by an organisation seeking change, to be successful, are rationally based on a cost/benefit analysis (Jenkins, 1983, p. 528). Therefore, the success of any change as desired by an organisation depends on its financial and social capital (McAdam, 1982, p. 20). The theory contests that social movements emerge not because of personal dissatisfaction, but because of the availability of resources to support these feelings of discontentment (Jenkins, 1983, p. 528). Jenkins notes that there is a clash between the understanding of social movements through the lens of resource mobilisation and that of collective behaviour. These collective behaviour approaches, which were dominant in the 60s (1983, p. 528), form a “meaning-oriented” understanding (Atkinson, 2017, p. 25). This is distinct from resource mobilisation theory, as collective behaviour understandings of social change little relied on organisational precision (Jenkins, 1983, p. 528). Collective behaviour understandings of social change identify movements as an extension of collective behaviour which encompasses goals of personal change (such as seen in religion/conversion) and institutional (such as legal change). Resource management approaches identify social movements as those which seek institutional change. It does not exclude personal change from being a goal of a social movement but ingrains it with the institutional change (Jenkins, 1983, p. 528). Jenkins identifies this failure to address personal change as a key weakness of the resource management approach. Collective behaviour may be more readily applicable in smaller organisations which rely on a charismatic leader with centralised control. These groups may also have diffuse outcomes, as they lack the resources necessary to successfully accomplish their goals (1983, p. 528).

The traditional explanations of social change as seen in collective behaviour theory (as well as others) are focused on short-term grievances individuals hold with a society, created by the form of structural strain as we saw in Griffin’s formation of these movements. Jenkins argues that in contrast to this grievance-focused position, resource mobilisation theory states that these grievances are secondary to long-term changes in group organisations due to the allocation of economic capital (1983, p. 530). The debate about the validity of each approach comes down to this difference, of a grievance-based approach and one of long-term change (defined as organisation, resources and opportunity). Jenkins provides examples of research that has supported each of these theoretical frameworks and providing a new example which seems to reject the premise of both. The entrepreneurial model is utilised by activists without a significant recent increased in grievances and can operate with little resources (p. 531). This eschews the defining features of both collective behaviour and resource mobilisation theory.

Collective action framing

The concept of collective action framing has gained significant capital in social movements following the works of Snow and Benford, who have brought the theory to prominence. They note in their article ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment’ that this rapid increase in prominence can be seen in the references of the journal Sociological Abstracts (2000, p. 612). In 1986 the journal contained just one reference to framing, and in 1998 the number of references has jumped to 43 (2000, p. 612). They note that framing is regarded as a central dynamic in understanding social movements. Although present in Goffman’s work ‘Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organisation of the Experience’ (1974), the term has developed substantially. As originally posited by Goffman, frames are an interpretation that can be used “to locate, perceive, identify, and label” instances of a value in their context (1974, p. 21). In Goffman’s work frameworks are used as an explanation for the different ways in which we contextualise information. In discussing a matter with one individual, we may include details we would not with others. A simple example of this distinction is the sharing of personal information. The details of personal information shared with a close family member or partner and a doctor are distinct, although may overlap. Goffman gives an example of this framing in action with the example of a coroner, in highlighting the difference between the “manner of death” and the “cause of death” (1974, p. 24). Although both connected, and both being information communicated to or from a coroner, they hold different meanings. Goffman argues that the cause of death is strictly rooted in the biological understanding, while the cause is more complex and perhaps social (1974, p. 24). The distinction can be clarified in the example of a homicide. If the cause of death is blunt force trauma, the manner could be identified as assault (and subsequently murder). As presented by Goffman, framing can be summarised as the perspective we view the wider world. Snow and Benford state that framing is an “active, processual phenomenon that implies agency and contention at the level of reality construction” (2000, p. 614). This dynamic and shifting application is utilised (consciously or not) by every individual, and it shapes their perception of the world and those around them. It is distinct from even those with shared life experiences, as opinions are central to this construction. Although it could be argued that shared life experiences may incline individuals to similar opinions. This perspective is then communicated to others through any interaction (talking, writing, reading etc.). In a modern context, this framing is present online in a personal (social media) and organisation sense (news sites).

Goffman’s use of framing readily applies to any social interaction and has been expanded upon for multiple fields. In the field of activism and social change, collective action framing has become a prominent tool in understanding the organisations behind this change. As discussed in the previous paragraph, the use of collective action framing in the literature has increased readily in the 90s; primarily because of the understandings as provided by Snow and Benford. This process of framing is focused on how a social movement defines itself, and how they communicate this to their target audience. This helps to support the goal of gaining support for their social movement (Tarrow, 1998, p. 110). The success of any movement of social change relies on the effective communication of this framing (Noakes and Johnston, 2005, p 1-2). This takes the form of what scholars have called collective action frames processes of framing a debate intending to form a collective action (Snow and Benford, 1988, p. 198). These frames allow organisations to simplify and condense the outside world to mobilise potential supporters. These frames allow organisations to demobilise and demonise their opponents (Snow and Benford, 1988, p. 198).

Snow and Benford identify the three main tasks of collective action framing as ‘diagnostic framing’, ‘prognostic framing’ and ‘motivational framing’ (2000, p. 615). In using these methods of framing, social movement organisations seek to motivate and mobilise their supporters. The first, diagnostic framing, communicate the problems with society to a wider audience. In the case studies as examined by Snow and Benford, a subset of framing named as “injustice frames” is highlighted as the dominant diagnostic selection (Gamson et al in Snow and Benford, 2000, p. 615). Benford gives an example of the potential of diagnostic framing in using the debate of nuclear disarmament campaigns of the 1980s (1987, p. 67-74). He notes that those activists at the heart of this debate could not decide on which aspect to ‘blame’ in their activism. One group of activists wanted to focus their campaign on the potential of a nuclear threat, whilst another wanted to focus on a decline in morality and abuse of nature and technology. The diagnosis of one was that of the existence of a nuclear threat and the potential harm it could cause the population, whilst the others identified the drop in morality and subversion of nature as the primary cause for concern. Although these two perspectives are distinct, the difference is subtle as each group ultimately views the same threat with alternative objections. Their aims are singular on this issue, but their framing of the point of contention is anything but. Connected to this form of framing is that of ‘boundary framing’, in which activists seek to characterise those active in a debate as ‘protagonists’ and ‘antagonists’ (Hunt et al. in Snow and Benford, 200, p. 616). This enables the diagnostic phase of collective action framing to form an adversarial dynamic, of those who implement the fault with society and those who seek to change it.

The second method of framing, prognostic, seeks to identify solutions to those identified in the diagnostic stage of framing. Although it follows on from a diagnosis of an issue, the two can be separate and do not necessarily follow a continuous stage order. Snow and Bedford state that his prognostic stage does predominantly follow on from the diagnostic stage, and that the solutions presented are restricted by the framing used in the previous stage (2000, p. 616). Following on from the example given by Benford for the diagnostic stage, prognostic framing could be seen in the cause of nuclear disarmament. This restriction of the prognostic framing can be seen in the two alternative diagnostic frames; namely the nuclear threat and the decline in morality. The group which focused on the nuclear threat could present a prognostic framing that is straight forward, an abolition of nuclear weapons and power. The second group may present an alternate prognosis, one that is harder to predict. If their qualm is with morality and the subversion of nature, they may additionally campaign for the abolition of GMOs alongside the nuclear issue. If we restricted their prognosis to the nuclear issue, perhaps even then they may hold alternative views on the technology: including a restriction to research in related fields. Snow and Benford note that this framing of solutions includes the refuting of those put forward by opponents (and their character, morality), which they call “counter-framing” (2000, p. 617). Snow and Benford give a detailed example of this on democracy in China, with campaigners actively painting themselves as self-sacrificing and driven by community devotion. This was in response to the Chinese government, and those who support it, who labelled these campaigners as “revolutionary”, “chaotic” and in opposition to traditional Chinese values (Zuo and Benford in Snow and Benford, 2000, p. 617).

The third and final main task of collective action framing is motivational. This is the framing of the debate that allows social movement organisations to continuously motivate their supporters. This is what Gamson refers to as the “agency” element of collective action framing (Gamson in Snow and Bedford, 2000, p. 617). The use of language in this phase is identified by Snow and Bedford in four ‘vocabularies of motive’; severity, urgency, efficacy and propriety (2000, p. 617). The first of these focused on the scale of the cause or threat. The second on the time-scale with the third of how efficient it could be dealt with. The fourth focused on the conventions of previous activist work. These vocabularies of motive used together to provide a “compelling account” for justification of their engagement with the activist movement (p. 617). Snow and Benford note the need for further research into this task of collective action framing, and from my exploration of the sources available, I have not discovered new research on this niche of collective action framing since the publication of their journal article ‘Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment’.

These three tasks, as identified by Snow and Benford, will be central to my case study. They are at the heart of the research questions posed. Snow and Benford, and other writers have given extensive detail on previous research that has dealt with framing. They conclude that collective action framing processes are not static but are continuously modified and changed. This dynamic process is affected by changes in society which social movement organisations are embedded within. The three tasks are connected to the period of rhetorical crisis, as identified by Griffin earlier on in this chapter. Although Snow and Benford would argue that this shaping of rhetorical is not one of crisis, at least from an organisational point of view (but perhaps in terms of the cause). This phase does, however, relate to a period that has already begun, the social issue is being raised by a social activist organisation and the period of discourse (or the application of a frame) has started.

Online activism

Consumer activism online is an emerging body of literature, with online studies focusing on how the internet can improve business and consumer relations such as those presented by Lutz et al (2014). Minocher notes that the literature holds very little in terms of how customers are able to hold companies accountable (2019, p. 620). While there is a small body of work that addresses the interaction between consumers online and advertisers, some examples are present. Nip provides an early example of the planned introduction of a direct mail marketing database in the 1990s (2004, p.235). This was planned by the company Lotus Development Corporation and was strongly opposed by a large portion of the online community at the time. Gurak underlines the use of “newsgroups, emails, and a specifically formed discussion group” (Gurak in Nip, 2004, p. 235). The result of this campaign was a success, with Lotus never releasing a product (Gurak in Nip, 2004, p. 235).

3 Methodology

A case study was chosen for this research for several compelling reasons. A qualitative research approach was clear in the initial stages of this research, as ‘Stop Funding Hate’ is an organisation with clearly self-indicated social aims. These aims are stated in all their created resources (such as social media) and require a meaning-based approach in analysis. Stop Funding Hate is an actively operating organisation at the time of writing this research, so it is appropriate to select case studies as this is a contemporary event (Yin, 2014, p. 9).

Research questions

According to Stake, qualitative approaches are required when research questions demand an exploration of an event (1995). This begins with “how” and “why” questions, as according to Yin, these questions “deal with operational links needing to be traced over time” (Yin, 2014, p.10). The questions I held as approached this research were as follows; ‘How well do activist organisations accomplish goals which help to create change? Why or why not has this been effective?’, ‘Why is there a focus on activism online as opposed to traditional forms of activism? How has this benefited the campaign?’ and ‘How effective have activist organisations been in transmitting their messages (their goals, objectives and other views)?’. However, I came to realise that these questions did not reflect the true intention of my research. The intention of my research is to use Stop Funding Hate as an exploration and example of the theoretical foundation of this dissertation: the application of collective action framing. How well does this form of analysis work in research? How does it relate to discourse and content analysis, more traditional and wide-ranging theoretical theories? The three questions I initially held at the start of this research did not target this ambition to test this theory. They were also wide-ranging, such as the first in my list: ‘How well do activist organisations accomplish goals which help to create change?’. For my research to be successful, my questions on effectiveness must be more concise. Simply asking how effective a strategy is leaving the research too open-ended. As I progressed my questions adapted, as they are presented here.

- How does Stop Funding Hate communicate its core institutional narrative, principles and aims?

- How does Stop Funding Hate implement collective action framing on the resources it curates?

- How well does collective action framing work as a tool of analysis?

These questions have enabled me to pursue a unique and experimental piece of research, which has held my interest far more than any other form this dissertation has taken. In the literature review, I recounted previous studies that involve collective action framing, thanks to the work of Snow and Benford (2000). Without it, I would not have discovered the potential scope of collective action framing and realised the potential for its implementation in this research. I also summarized activist organisations and gave a contextualisation of the organisation Stop Funding Hate through modern research on activism that takes places online. While Snow and Benford provided this research with a foundational footing for its research, and its exploration is clear in merit, so too is the exploration of modern activism. While the purpose of this dissertation is to explore collective action frames, with the example given as Stop Funding Hate, to do so we needed an understanding of the purpose and the social arena in which this organisation operates.

Case Studies as a social research method

The choice of a case study as a qualitative research method came in my reading of Gilbert, who provided the example of another pair of researchers work (2012, p. 36). The study from 2007 focuses on the installation of mobile phone towers in Fife, Scotland. Law and McLeish knew of the limitations of both qualitative, and of case studies. The lack of generalisability, of applying the results of the study to a wider understanding of society, is limited (Gilbert, 2012, p. 36). However, Law and McLeish compared their findings from this protest to a theory of protest and concluded in their findings that this did not explain this phenomenon in Fife (Law and McLeish in Gilbert, 2012, p. 37). This is also the aim of my research, to use the example of Stop Funding Hate to examine the theories and ideas presented in my literature review to assess their viability. As Gillham states, “research is about creating new knowledge” and this approach of a synthesis of literature alongside an example, researched through the process of a case study, will create new knowledge and understanding of this area of social life. Therefore, my most important and final research question as presented in the previous section is ‘how well does collective action framing work as a tool of analysis?’ The use of a case study in this manner falls under Pamela and Susan’s (2008) conceptual framework for case studies. In their article ‘Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers’ Pamela and Susan provide definitions and examples of different types of case studies. The research as approached in this dissertation would fall under the ‘instrumental’ form of a case study (Pamela and Susan, 2008, p. 548-549). Like the Law and McLeish example given earlier, an instrumental case study is one that is used as a means of providing insight into previous research and theory. The case itself is “of secondary interest”, playing an assistive role in our understanding what came before (2008, p. 548-549).

The use of a case study in this fashion was further strengthened by Yin, a prominent case study researcher. As discussed in my opening paragraph for this chapter, a case study is an appropriate means of social research if the event or issue at hand is contemporary (Yin, 2014, p. 6). Stop Funding Hate falls under this definition as it is still an operating activist organisation. However, the viability of a case study is also clear because of the limitations of social research. As Stop Funding Hate is an independent organisation and not an individual, there is no research methods that could manipulate the behaviours of those involved (Yin, 2014, p. 12). Besides this distinction between an individual and an organisation, Stop Funding Hate represents a phenomenon. While it is one organisation, and there are no levers of control we could have to turn the research into an experiment. While it is clear that most social research is not of this kind, some do exist, and it holds a strong presence in psychology. This is briefly highlighted in an example given by Yin, such as a study where researches provide different vouchers to purchase goods and services (Boruch and Foley in Yin, 2014, p. 12). Stake states that in a case study, it is the interpretative position of the researcher that dominates the qualitative function of a case study (1995).This aspect will act as both a benefit and a criticism of my research. As the primary interest of my dissertation is to create a synthesis of the existing literature and apply it to the example of Stop Funding Hate, and a requirement of interpretation is fundamental to the success of this aim.

Design and methods

The primary purpose of this dissertation is to provide an expanded literature review with a case study example, therefore there is some restriction as to the amount of data sources I can make use of. The aim of the case study itself it to provide a biographical and contextual understanding of Stop Funding Hate, for there to be a basis that the theory can be applied. In this interest, and because of a lack of access to the team behind Stop Funding Hate, a decision was taken early in the process to use data from online sources. Yin gives a list of the types of evidence available to a case study researcher as; documentation, archival records, interviews, direct observation, participant-observation and physical artefacts (Yin, 2014, p. 106). This conceptual framework of a case study is not exclusive in its viability, as others have been constructed with varying types of research methods (Reddy and Agrawal, 2012, p. 3). One such example is presented by Pamela and Susan (2008, p. 544), who argue that both Stake (1995) and Yin (2003) base their frameworks on a constructivist paradigm. These are not however all required to make a piece of research a case study, as outlined in the conceptual framework as outlined by Reddy and Agrawal (2012). While Yin and others strongly emphasise the use of primary sources for case studies (2012, p. 3), Reddy and Agrawal provide a framework that employs the use of secondary sources in what they label as “Type II Case Studies” (2012, p. 3). The traditional Type I case study is typically focused on the other forms of evidence as given by Yin; interviews, direct observation and participant-observation (2014, p. 106). Yin argues that the most important use of documents and archival records is that of a supportive role, to “corroborate and augment evidence from other sources” (2014, p. 106). However, in a Type II case study, the focus is on the content of the secondary source. This allows an analysis of the secondary source itself, of its authorship and reliability. In the context of my research, the secondary source basis for my Type II study is one created by an organisation. As I am taking an instrumental approach, the bulk of my dissertation is based on a literary review and fusion of a case study. Therefore, the sources utilised in the case study are not fundamental to the value of this research and rather than being a weakness, they are of primary interest to this research itself. Each of the research questions warrants an analysis of the content of a secondary source itself, of its effectiveness and usability. This is apparent as the core interest of the dissertation is in the social construction of these sources.

The focus of the research collected for this dissertation will be on documents. According to Denscombe documentary research exist as digital communication, written text and visual sources (2014, p. 225). The traditional advantages of using documents as a form of research are twofold, they can be used as evidence of something. In the case of a written source, this could be a historical source such as a biography or an account of an event (Haralambos and Holborn, 2013, p. 934). The second advantage is the concept of a permanent record, it holds the potential to transcend the research it is a part of; this is due to the continuation of access to these documents (Denscombe, 2014, p. 226). Although this continued access is subject to the condition and security of the source and may not be preserved later. A text that is widespread in its circulation may hold a long lifespan in terms of accessibility, but those that are not may be more prone to destruction. Compared to other research methods this value is more apparent, as Denscombe notes, a document is in its final form as a research source (2014, p. 226). Compare this to an interview, and it is apparent that you cannot go back to the research stage to ask questions. While it is true that the interviews are published as a document, the difference lies in the approach to the source.

Data collection

The document that will be the focus of this dissertation is the Stop Funding Hate website, https://stopfundinghate.info/. Denscombe notes that websites can be treated as documents in their own right, with the images and text analysed for any potential meanings (2014, p. 228). The selection of the Stop Funding Hate website as the source for this case is three-fold. First, it provides an informational basis for discussion around the group; a historical biography and record of past actions and their aims. It also addresses a traditional weakness of documentary research. The selectivity of sources can often be incomplete or selected with a bias, but by focusing on one source this criticism is eliminated as there is no bias in this selection. For example, alternative approaches were considered in the initial stages of this dissertation which may have been subject to selection bias. One initial idea was an analysis on the reporting of Stop Funding Hate, but even with a rigorous selection process, some sources of news would be left out. Alternatively, Stop Funding Hate’s twitter feed could be analysed. This was never a consideration of this piece of research, as the intention is to give an in-depth theoretical basis for Stop Funding Hate. However, if it was selected, the bias in selection would require additional justification in the research design. This selection of one source follows advice from Pamela and Susan, who highlight the necessity of binding the case to a specific context to keep a reasonable scope (2008, p. 546-547). While the scope of this research is more limited than Pamela and Susan suggested it provides other benefits. This constriction ties directly into one of my primary research questions, in exploring the credibility and authorship of the Stop Funding Hate website. The benefit of other sources in this regard is questionable, as the basis for interpretation lies in the fusion between the theory and analysis of the website. This bounded selection directly plays into the fundamental theoretical basis for this research, collective action framing. In discussing this singular source, insight into its construction is gained; the frames and rhetorical devices used. Alternate sources of data collection would not be viable for the research questions as that this research is exploring, as the website and its social construction are the central point of interest.

In the stage of data collection, the website will be captured and imported to the software NVivo, a qualitative data analysis programme. Bazeley and Richards note that qualitative research often begins with a clear theory or hypothesis in mind, to test, and the use of software such as NVivo allows the researcher continued access to these data sources (2011, p. 3). The use of this software is particularly useful as it allows the research to begin without a “clear starting line”, an exploration into what the analysis could be (2011, p. 3). In ‘Qualitative Analysis Using NVivo’ by Woolf and Silver, they note that NVivo is a powerful tool for qualitative social research, but it is a mistake to view it as a cousin of quantitative tools such as SPSS (2018, p. 2). The program does not provide an analysis, and it is important to enter this process with one in mind. While it can help you store information, and collate and categorise it, its analysis is interpretative and is therefore outside the scope of the programme as designed. The version I have used is NVivo 12, acquired for use on my home computer through the University of Hull’s digital access repository. Any tools on other versions of NVivo were not available to me, and therefore do not contribute to this research. Information from the document, https://stopfundinghate.info/, was captured using the NCapture tool and stored. This had numerous benefits, including allowing me to return to the same material as presented in my first analysis without fear of a change in content. Like any website, the presentation and content could change at any moment, so a copy of the site as initially viewed was extremely useful. While NVivo offers many tools for the qualitative researcher to present their information, I decided that quotes will be used to demonstrate my findings in the next chapter. This allows me to focus on the text and meaning behind the words, as analysis on presentation would expand this research past the word count. NVivo was also vital in this dissertation for its ability to store documents, which greatly helped with the organisation of past research and literature on the subject. Memos were also an important tool, allowing me to keep notes and track any thoughts on the research or on the document at the core of this case study (the stop funding hate website).

Data analysis

The analysis of the data collected will be achieved through the framework as developed by rhetorical analysis, a form of qualitative research that is connected to other methodologies such as discourse analysis and content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004, p. 16). The rhetorical analysis provides insights into a constructed narrative that a group, individual or other text may be communicating (Zachry, 2009, p. 68). This allows the researcher to examine the purpose of this communication. Rhetorical analysis affords the researcher a clear four-point framework for research, as outlined by Zachry. These four key stages of research are; the identification of text for analysis, the categorisation of the text according to its purposes, the identification of constituent parts and finally the interpretation and discussion of one or more aspects of the text in connection to theoretical concepts (2009, p. 70). In addition to this, the rhetorical framework draws upon three distinct bodies of theory; traditional, new rhetorical and critical-postmodern (2009, p. 70). The traditional strain comes from the work of Greek philosopher’s, such as Aristotle (2009, p. 70). The rhetorical theory describes the three ways texts are designed to communicate with others; deliberative, forensic and defined. Deliberative is focused on the discussion stage of rhetoric, in which past events are discussed and their implications on society. Forensic relates the way in which groups or individuals assess modern society, to decide what is just and unjust – this includes a continuation of the deliberative stage as a focus is on the past events that led to this point. Lastly is the demonstrative stage, in which these groups or individuals seek to establish the merit of something, perhaps a proposal to fix a previous solution. This connects to the motivational and prognostic stages of collective action framing, in which social movement organisations attempt to give solutions to injustices in the world and then continue to enthuse their activist base. This connection to the motivational stage is in the continuous discussion of their proposed solution, as we can see in the example given by Snow and Benford on the nuclear disarmament campaign in the previous chapter (see page 8 of this paper). New rhetorical and critical-postmodern both draw upon and then improve ideas as presented in the traditional schema. The principal difference is its application, as according to Zachary, traditional rhetorical analysis focused on performing a communicative act through a cataloguing of textual elements to being more open to the meanings behind these social terms (2009, p. 72 & p. 74).

Given the principal research question ‘how well does collective action framing work as a tool of analysis?’, the primary form of analysis will be rooted in collective action framing. In deciding how this would be used as a tool of analysis, the rhetorical analysis was identified as a framework thanks to the four stages as identified by Zachry (2009). With its roots in discourse and content analysis, rhetorical analysis as a rich tradition of application in qualitative social research. The framework as presented by Zachry has been adapted for use in this dissertation, following this four-act structure. The initial stage of identification of text for analysis was determined from the early stages as the Stop Funding Hate website. As a social construction of the organisation Stop Funding Hate it is the ideal candidate for an exploration into the curation of framing. This enables this research to follow the instrumental form of a case study as identified by Pamela and Susan (2008, p. 548-549). The second stage is that of categorisation of texts, which enabled with the application of NVivo software. Text in the files as captured by the NCapture tool allowed the text to be sorted into nodes. Woolf and Silver highlight the use of nodes for concepts, which enhances the organisation of the materials and eases the process of analysis (2018, p. 87). The identification of constituent parts is linked to the previous aim, as this categorisation of the text is in part the identification of concepts. In this research, the identification is of the use of collective action framing.

4 Findings

The Stop Funding Hate website is designed like many organisational websites and offers information about the campaign and its goals. This information includes, but is not limited to, a history of previous actions and the result of these actions. It also holds information on how the user can interact with the organisation. In order to properly discuss the findings of this research, it’s logical to first outline the basic layout of Stop Funding Hate. The website is split into its home page and alternate sections, accessible through a navigation bar. The figure below this paragraph illustrates the site-map of the website, with the key sections being; the homepage, ‘Get Involved’, ‘Our Videos’, ‘Campaign Updates’, ‘About the Campaign’, ‘Shop’ and ‘Donate’. Additionally, the sections ‘Get Involved’ and ‘About the Campaign’ have additional sub-sections. The figure was created with https://www.gloomaps.com, with the titles imputed manually based upon the PDF files as collated in NVivo.

The titles for each section define what the user is likely to expect of it, with simple and meaningful language. The informational account of past actions is primarily located in the sections ‘Our Videos’, ‘Campaign Updates’ and ‘About the Campaign’. Information on how to engage with campaign is spread throughout the website but is dominant in the sections ‘Get Involved’, ‘Our Videos’, ‘Shop’ and ‘Donate’. While the historical/narrative sections do insight engagement from the user it is passive. These engagement focused sections offer instruction on potential activists’ engagement with the campaign. One section, ‘Our Videos’, is a combination of the informational and engagement focused texts. It both communicates the messages as desired by Stop Funding Hate and allows interaction from its users in the form of comments and likes (as the files are embedded YouTube videos).

Research question 1: How does Stop Funding Hate communicate its core institutional narrative, principles and aims?

The purpose of this research question is to contextualise the contents of the following question, which determines the application of collective action framing. This question mostly deals with quotations from the source material, placing them in the sitemap and allowing the following question to provide a detailed analysis. The home page is designed with the knowledge that it is the first section that the user interacts with and contains a summary of the actions and aims of Stop Funding Hate. The site is designed with neutral colours, mostly teal and white, and is presented in a logical manner. The first line of the page is “We’re making hate unprofitable by persuading advertisers to pull their support from publications that spread hate and division”. On the outset, both the past activities and future aims have been condensed to a singular sentence. Following on from this the website seeks to designate the problem as tabloid sensationalism, punctuated with a quote from the UN, “History has shown us time and again the dangers of demonising foreigners and minorities”. This is paired with a description of further insight from the UN, claiming that this international organisation has labelled some British newspapers of hate speech. The connection is strongest to the Daily Mail, with an image below the header of the page showing activists carry signs that read “Detox the Daily Mail”. It’s later stated on this homepage that Stop Funding Hate has compiled a list of ‘Ethical advertisers’ who do not advertise in the Sun, Daily Mail and Daily Express. This clearly identifies these three newspapers as the perpetrators of these actions. The background of this section is designed to look like Lego bricks, with the logo of the company being presented alongside this: this is an indication of one of the bigger success stories of the campaign. The text following this lays down the theoretical background for this connection, stating that newspaper editors hold strong incentives to run “sensationalist anti-migrant headlines”. This section also acts as a call to arms, highlighting the role of advertisers in supporting the economic element of newspapers. Stop Funding Hate argue that these private companies hold strong views on workplace and social issues, such as discrimination. The principal aim of Stop Funding Hate is clearly identified here, as they seek to make running sensational headlines a bad business decision. This lies in the tactics of the organisation, which is explored in other sections of the website such as ‘Get involved’. The remaining sections of the homepage relate to an engagement focus of the campaign, providing space for users to sign onto their email list and holding links to their shop. These both allow the organisation to present users with marketing and fundraising information (with the shop arguably being a form of both). The homepage, therefore, falls under both categorisations of purpose; informational and engagement. As the initial point of contact of the user, the benefit of this is clear: it acts a summary.

A detailed account of each section of the website would not be beneficial and would hinder the ability of this paper to explore the elements as required by the research question (given the word count). However, the homepage holds central importance to the messages delivered to the user, as it is the piece of a website that typically holds the most user-related traffic. I will only describe core elements of other sections of the website as they relate to core institutional narratives, principles and aims.

Institutional narratives, principles and aims

To begin the analysis of how Stop Funding Hate communicates these aspects, we must first conceptualise them. Loseke (2007) notes that narrative identity is present at “all levels of human social life” (p. 661) and therefore produces narratives that construct institutional identities. These identities are the imagined or socially constructed forms of characterisations present in organisations (p. 661-662). Therefore, the institutional narrative of Stop Funding Hate is akin to the characteristics and identity of the organisation. The values and motivations are at the centre of this issue. The principles and aims are easier to conceptualise, but also connect with the initial concept of identity. The principles and aims of any individual are at the core of identity, and this applies to organisations too.

Throughout the website these narratives are present. Returning to the homepage, the identity of the organisation is presented in firm opposition to anti-migrant ideologies and language. The sign-up input is prefaced with the slogan “join the campaign to make hate unprofitable”, which directly paints anti-migrant ideologies as hate based. In the section ‘Media hate and hate crime’, a subsection of ‘About the Campaign’, Stop Funding Hate insinuates that these sensational newspapers do not tell the truth: ”a free society relies on a media that we can trust – which tells the truth, and treats everyone fairly, whatever their religion, ethnic background, gender or sexuality.” This section then continues to justify this viewpoint with multiple sources of information ranging from newspaper headlines (both an example and those on which report on the sensationalism) and official sources. This includes citations from the 2012 Leveson Inquiry, the UN and the Council of Europe. All of this is designed to again underpin the point that the anti-migrant rhetoric present in tabloids helps to boost their sales in an environment of industry low print sales. They argue that this extreme coverage allows newspapers to boost their sales numbers, and therefore attract higher prices for the advertising space provided. This is emphasised by a quote from a former Daily Star journalist as displayed in this section, “The impression I got… was that… editorial decisions are dictated more from the accounts and advertising departments than the newsroom floor… stories which sell well… had to be sourced on a daily basis… This naturally led to fabrication…. Much more insidious was when this same philosophy was applied to stories involving Muslims and immigrants… a top down pressure to unearth stories which fitted within a certain narrative (immigrants are taking over, Muslims are a threat to security) led to casual and systematic distortions.”.

Research question 2: How does Stop Funding Hate implement collective action framing on the resources it curates?

This research question is designed to build upon the previous question, applying theoretical concepts to the elements discussed. In chapter two of this research an extensive account of collective action framing is presented by Snow and Benford (2000) and is the foundational basis for the analysis of this document. The three tasks at the core of a social movement organisation, as identified by collective action framing theory are; diagnostic framing, prognostic framing and motivational framing. The use of the NVivo node function was fundamental in the assessing of collective action frames in relation to Stop Funding Hate. The frames were split into the three tasks as outlined by Snow and Benford (2000) and coded along these lines. This provided ease of accessibility to each of the instances of the frames and provided insight into the spread.

Collective action framing

Before we can address how Stop Funding Hate implements rhetorical framing devices in the creation of their website, we must first identify instances of these diagnostic, prognostic and motivational framing. As outlined in the methodology section of this research, coding was used extensively for organisational purposes. This is in line with the framework as provided by rhetorical theory, namely ‘categorisation of the text according to its purposes’ and ‘the identification of constituent parts’. This too provides the research with some statistics for the use of frames on the website. In total, seventeen files were generated from the Stop Funding Hate website using NVivo’s NCapture tool. These files were in PDF form. This has numerous benefits, with the ability to return to the website as it first analysed as the key importance. This allowed the research to explore further research and helped shape the methodological basis for this dissertation. Following on from this stage of PDF collection, each file was assessed and coded. Nodes were added to each piece of text as deemed to represent a collective action frame, namely; the diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frameworks. When relevant, other action frames were codified following the outline as provided by Snow and Benford (2000). These were the ‘injustice frames’, as outlined by Gamson (in Snow and Benford, 2000, p. 15) and the process of ‘boundary framing’. In particular, boundary framing was used to codify language that showed the use of ‘protagonists’ and ‘antagonists’ in the narrative that is presented on the website (Hunt et al. in Snow and Benford, 2000, p. 616). As the Stop Funding Hate website is the construction of the organisation itself, and not a critical analysis of its actions, every aspect is curated intending to deliver a message. The implication of this is that almost all the text as presented on the website fits into one of the frames being used as an analysis. The exception to this is the legal text, alongside some navigational items. While the legal text is exempt totally from this framing process (such as the notification of the use of cookies), navigational items are not completely removed from this the use of frames.

Now I have identified the frames that have been categorised in this research, I will examine examples of each form of framing as present on the Stop Funding Hate website. In addition to this, I will contextualise their location on the website and connect this to the categorisation of ‘information’ and ‘engagement’ focused sections of the site.

Diagnostic framing

This example of diagnostic framing is an attempt to communicate the connection between the media and hate crime. This is noted by Snow and Benson as a key component of diagnostic framing and connects to what Gamson described as an “injustice frame” (Snow and Benson, 2000, p. 615) (Gamson in Snow and Benson, 2000, p. 615). Stop Funding Hate communicates their perspective of this connection aptly with a respectable source, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. This is located in the ‘Media and hate crime’ section of the website and most of the content on this page backs up the ideological aim of this activist organisation.

This quotation is again taken from the ‘Media and hate crime’ section of the website and continues the narrative of a connection between hate crime and the media. They again use reputable sources in the form of Leicester University Centre and Cambridge University. This quote also represents the first time Muslims are mentioned in relation to this hate crime. While previous sections have specified the demonization of foreigners and minorities, this is the instance in which those minorities are specified. Later on in this section, Stop Funding Hate provides an example of a headline that captures this message. It is represented in the figure below.

Injustice and boundary framing devices are present in this diagnostic stage too. The injustice framing devices are clear in Figure 2 and throughout the website. Stop Funding Hate argues that this form of language demonises minorities, with the language used designed to present these minorities as an ‘other’, separate from mainstream British society. This too highlights the boundary framing by the newspapers. They label one minority as antagonists, while they and their readers are the protagonists. Meanwhile, this form of boundary framing is present in Stop Funding Hates presentation of newspapers such as the Sun. To this social activist organisation, sensationalist newspapers are the antagonists perpetrating hateful messages; with the supporters of Stop Funding Hate being represented as the protagonists.

Prognostic framing

The core aim of the Stop Funding Hate is represented in this initial statement, as I pointed out in the previous paragraph, ‘Research question 1: How does Stop Funding Hate communicate its core institutional narrative, principles and aims?’. This immediately communicates the goal of to the user, and in tandem with their name, provides a simple and effective prognostic form of framing. Stop Funding Hate knows the impact these sensational headlines have had on society and knows that many individuals are aware of this issue. The Daily Mail has long been known to be a source that has mislead the public and published negative and sensational pieces in order to attract readers (Kmietowics and Godlee, 2012, p. 6). Stop Funding Hate acts upon this perception, allowing it to present its prognosis directly to its users without an immediate diagnostic framing. Therefore, the homepage begins with this prognostic statement, rather than an explanation of the causes. This continues on the homepage under the ‘Role of advertisers’ section with “Newspaper editors have a strong incentive to run sensationalist anti-migrant headlines: it boosts their readership – and that means they can earn more from advertising.” Again, Stop Funding Hate underlines the theoretical basis for their argument; to dissuade newspapers from running these anti-migrant headlines, advertisers should be targeted. “Many of these advertisers have strong ethical stances on other issues: on discrimination in the workplace, on their supply chains, on their role in their communities. But when it comes to choosing which publications they fund with their advertising budgets, their own ethics and values have often been ignored. Until now”. This quote directly follows the previous one and provides not only a continuation of the prognostic framing, but the beginning of a motivational one.

This quote was taken from the ‘Get involved’ section of the website, which outlines the ways in which an individual can contribute to the campaign. This quote again emphasises that advertisers hold values, and outlines Stop Funding Hate’s mission to contrast the values of companies with the stances of the mediums they advertise within.

This quote is at the core of the campaign’s actions, as is their primary method of raising awareness and creating change. Their primary strategy is to take images (screenshots of online articles, photos of physical copies) of newspapers running anti-migrant (or otherwise hateful) content. They then send on this juxtaposition to the advertisers on social media platforms, primarily on Twitter.

These prognostic framing actions are in line with the description as given by Snow and Benson, as identification of solutions to the problems identified in the diagnostic framing stage (2000, p. 616). As I noted in the literature review, these two framing conceptualisations do not follow a continuous order and can be separated. As we have seen in the discussion of the diagnostic and prognostic frames in this section, the Stop Funding Hate opens with a prognostic framing device rather than a diagnostic one.

Motivational framing

Motivational framing is deeply interconnected with the other two frames presented in this case study. As the website of an organisation, every aspect can be interpreted to motivate their supporters. While the website serves the goal of recruitment, user engagement comes from those who have already seen the activities of the group, and therefore would fit into the continuous motivational category. While I do not hold any supporting evidence of this, the bulk of the activities as enacted by Stop Funding Hate and its supports are on Twitter. In the prognostic section, I presented an example of the solution that this organisation encourages. “Campaign online – take screenshots of advertisers on the Daily Mail and tweet the advertisers, asking them to stop their online advertising for these sites. Remember to tag @stopfundinghate and keep it polite and friendly”. The primary form of exposure that the group receives is therefore through Twitter.

Research question 3: How well does collective action framing work as a tool of analysis?

As an instrumental case study, the purpose of this dissertation is to test the applicability of collective action framework as a tool of analysis. The methodology section extensively covers my justification for the framework present in this dissertation, drawing from a history of discourse and rhetorical analysis. So how well does collective action framing work as a tool of analysis?

Collective action framing has allowed me to categorise and provide insight into the language used for diagnostic, prognostic and motivational purposes behind the tool of a social movement organisation. This analysis, although qualitative in the selection, has provided me with a rudimentary quantitative perspective into the presentation of frames. In total 17 PDF files were collected, with text from each page being extensively coded. These nodes allowed easy access to the text while showing the number of files each framing device appeared on and the total number of references. Diagnostic framing appeared on 15 of the PDFs, with 43 references. Prognostic on 14 PDFs, with 36 references. Motivational appeared on 17 PDFs, with 73 references. This provides insight into the language used, and as discussed in the previous research question, motivational framing is deeply interconnected between the other two forms of framing. As a website designed by the social movement organisation itself, this is not surprising.

Collective action framing has given insight into the tactics used by a social movement organisation, their framing of debate and the success of this methodology. I would argue that Stop Funding Hate has successfully fulfilled these three tasks as outlined by Snow and Benford (2000), revealing the meanings behind these messages. Snow and Benford state that framing is an “active, processual phenomenon that implies agency and contention at the level of reality construction” (2000, p. 614). The identification of framing tasks in this dissertation shows the motivations behind a social movement organisation in the development of this reality construction. While this can be implemented consciously and unconsciously, it is present Stop Funding Hate’s website. This is the ultimate benefit of collective action theory, it has enabled the categorisation of qualitative and interpretive labels, providing an understanding of their presentation. The extent of which Stop Funding Hate actively deployed these framing devices is outside the scope of this research, however, they are present. As a website designed by the group, there is no prospect that the purposes of the text were not curated for the group’s purposes.

5 Conclusion

The research questions used in this dissertation were designed to build upon each other. The first develops an understanding of Stop Funding Hate as an organisation, the second provides the application of collective action theory and the third examines the success of this process. This provides a logically sequence of the presentation of data collected in the research stage and holds its own in-depth section of discussion. As the purpose of this dissertation was to provide an experimental use of collective action framing as a tool of analysis, a research question dedicated to its success was necessary.

This experimental research provides a new framework for an analysis, fusing rhetorical analysis and the collective action framing theory. This potentially provides the basis for further research on social movement organisations. There is scope too for further research on Stop Funding Hate. As an organisation focused on a unique goal, the discontinuation of adverts that support hateful content, there is a strong goal. In the initial planning stages of this dissertation I had planned to include this element more, but due to the restriction of length it could not be combined with the experimental framework. An analysis into their work on Twitter would be one example of research that could be easily put together. This was not considered for this dissertation as it did not meet my interests as much as the final research aims. The website of Stop Funding Hate provided an excellent exploration of framing theories, as it was a construction entirely made by the group. Unlike on Twitter, where the UI and UX are a set experience for most users, Stop Funding Hate had creative control over every aspect of their website. This paired with the aim to explore collective action framing with a rhetorical analysis framework provided me with the chance to create a unique and experimental dissertation.

In the literature review I explored the historical understandings of social movement theories, then gave an in-depth account of collective action theory. Finally, the literature review contained a brief contextualisation of the field that Stop Funding Hate operates in. Due to the length of this dissertation, this aspect is substantially shorter than originally written. In the polishing stage of writing the majority of this was cut down. It originally included a large section on tabloid journalism, and an exploration behind the reasons that advertisers are responsive to this form of activism. As the dissertation’s primary purpose is the fusion of collective action theory and rhetorical analysis, this section was not prioritised over the extensive methodological chapter. The methodology chapter went into extensive detail of the plan I held for my dissertation and is the longest chapter because of this. The use of Stop Funding Hate as an instrumental case study was developed through the framework as outlined by Pamela and Susan (2008, p. 548-549). The use of the rhetorical analysis framework and the utilisation of NVivo was explained here too. Each of these aspects were fundamental to outcome of this research.

6 Bibliography

Atkinson, J. (2017). The Study of Social Activism. In Atkinston, J (ed.) Journey into Social Activism: Qualitative Approaches (pp. 3-26). New York: Fordham University.

Bazeley, P. & Richards, L. (2011) The NVIVO Qualitative Project Book. Thousand Oaks, CA. Sage Publications.

Benford, R. (1987). Framing activity, meaning, and social movement participation: the nu- clear disarmament movement. PhD thesis. Univ. Texas, Austin, 297

Benford, R., Snow, D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. Int. Soc. Mov. Res. 1:197-218

Benford, R., & Snow, D. (2000). Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611-639.

Denscombe, M. (2014). The Good Research Guide: For small-scale social research projects (5th ed.). Glasgow: Open University Press.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2003). The landscape of qualitative research: Theories and issues (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Fulcher, J. & Scott, J. (2011) Sociology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gauntlett, D. (2000) Web Studies: Rewriting Media Studies for the Digital Age. London: Arnold.

Gilbert, R. (2012). Researching Social Life (3rd ed). London: Sage Publications.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of the Experience. New York: Harper Colophon

Haralambos, M. and Holborn, M. (2013) Sociology: themes and perspectives. London: Collins Educational.

Kmietowicz, Z., & Godlee, F. (2012). Daily Mail story on care of sick babies was “highly misleading,” says BMJ editor. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 345(7886), 6-6.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Loseke, D. (2007). The Study of Identity as Cultural, Institutional, Organizational, and Personal Narratives: Theoretical and Empirical Integrations. The Sociological Quarterly, 48(4), 661-688.

Lutz, C., Hoffmann, C.P. & Meckel, M. (2014). Beyond just politics: A systematic literature review of online participation. In First Monday. 19(7), 1-36.

McAdam, D. (1982). Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCaughey, M. & Ayers, M. (2003) Cyberactivism: Online Activism in Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

Minocher, X. (2019). Online consumer activism: Challenging companies with Change.org. In New Media & Society. 21(3), 620-638.

Nip, J. (2004). The Queer Sisters and its electronic bulletin board: a study of the internet for social movement mobilization. In Donk et al. (eds.) Cyberprotest: New media, citizens and social movements. London: Routledge. 233-258

Noakes, J. & Johnston, H. (2005). “Frames of Protest: A Road Map to Perspective”. In Noakes, J., Johnston, H. (eds) Frames of Protest: Social Movements and the Framing Perspective. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. 1-29.

Pamela, B., & Susan, J. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544-559.

Reddy, K. & Agrawal, R. (2012) Designing case studies from secondary sources – A conceptual framework. International Management Review, 8(2), 63-70.

Smelser, N. (1962) Theory of Collective Behavior. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research: Perspectives on practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Tarrow, S. (1998). Power in Movements: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Vegh (2003) Classifying Forms of Online Activism: The Case of Cyberprotests against the World Bank. In McCaughey, M. & Ayers, M. (eds.) Cyberactivism: Online Activism in Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge. 71-96

Woolf, N. & Silver, C. (2018). Qualitative Analysis Using NVivo: The Five Level QDA Method. New York: Routledge.

Yin, R. (2014). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zachry, M. (2009) Rhetorical Analysis. In Bargiela-Chiappini, F (ed) The Handbook of Business Discourse. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 68-79