Abstract

The question of ‘Should you Just Eat?’ examines the ethics of Platform Food Delivery Services (PFDS) use of self-employed couriers in place of traditional employees. This aspect of the new platform company’s business model is the source of controversy in the debate; are PFDS simply exploiting workers using legal loopholes, or are these individuals actually benefitting from a new and progressive method of earning a living? The relatively new phenomenon is in need of further investigation to clarify what is needed to improve the working lives of the couriers.

My study used mixed methods of quantitative surveys to gauge whether the couriers feel the freedom and flexibility advertised by PFDS, followed by qualitative interviews to explore the experiences of couriers in relation to themes which emerged as a result of the surveys. The findings went against my initial research hypothesis and showed that couriers do benefit from working independently, they reported satisfaction with being their own boss, felt their pay was fair and being a courier fit well with their lifestyle. This led to investigating why autonomy is more valuable to these workers than security. Further research with the interviews, alongside the theory of precarious modern life provided by Bauman, shows independent working to be a useful tool in navigating the contemporary labour market, although the couriers did express a desire for extra support from their PFDS.

The study concludes by recognising the validity of the self -employed status of food couriers, the benefits of independent work are valued by the individuals choosing to earn a living this way. However, the system remains unfair, with the imbalance of power in favour of PFDS. In order to remedy this PFDS should be made to offer more support to couriers delivering for them, to negate some of the pressure and risk that occurs through their work. Secondly, to address the stresses of uncertainty of income, the group should be recognised as traditional low -paid employees are, and offered the same protections such as Tax Credits. These changes would improve the working experiences of food couriers making the form of work more sustainable in the long term without affecting the autonomy of the role.

Author: Claire Phillips

BA (Hons) Sociology, April 2020

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Theme 1 – Customers or Couriers?

- Theme 2 – Gig-work and Precarity

- Bibliography

List of Tables

Fig 1.0 Pie Chart for “Using Food Delivery Services (FDS) offers me freedom” – Courier

Fig 1.1 Pie Chart for “Using Food Delivery Services (FDS) offers me freedom” – Customer

Fig 1.2 Pie Chart Using FDS offers me flexibility – Courier

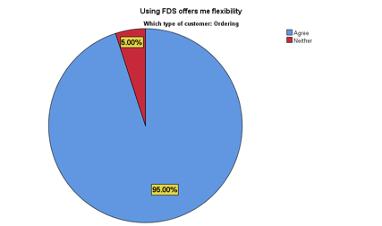

Fig 1.3 Pie Chart Using FDS offers me flexibility – Customer

Fig 1.4 Descriptive Statistics for value “How well flexibility works”

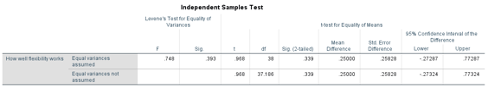

Fig 1.5 T-test Table of Results

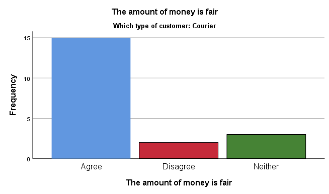

Fig 1.6 Bar Char for “The amount of money is fair” – Courier

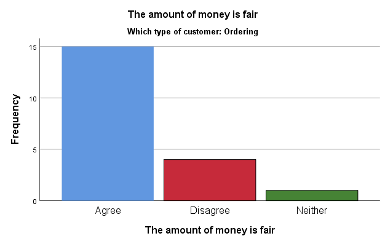

Fig 1.7 Bar Char for “The amount of money is fair” – Customer

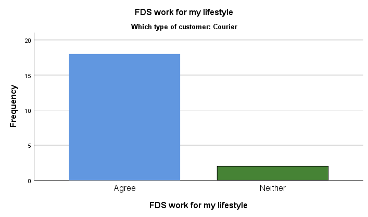

Fig 1.8 Bar Chart for “FDS work well for my lifestyle – Courier

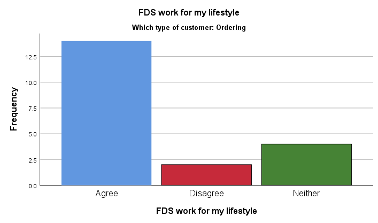

Fig 1.9 Bar Chart for “FDS work well for my lifestyle – Customer

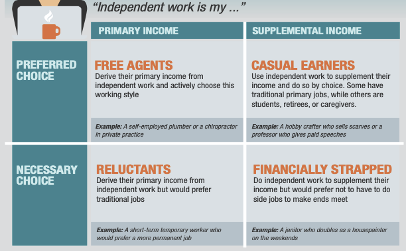

Fig 2.0 Table showing Manyika et al (2016:8) categories of Independent Worker

Acknowledgements

When I started this research project, I could not imagine finishing it, so to be typing this today as the last part of my finished dissertation, I feel a need to acknowledge the people who have helped me get to this point. Many thanks are due to the following

Alexander Ornella – for being a patient and supportive supervisor.

Kay Brady – along with Alexander, for advice and organising lovely writing retreats!

My Research Participants

My family and friends – for endless support and sustenance.

My Caravan – without which Coronavirus may have put an end to the whole thing!

Introduction

“Bike courier services are one of life’s great ideas in my opinion, you have this low paid, low maintenance workforce, to do this simple task, that people will pay through the nose for, and all the workers have to do is be less lazy than the customers”

Deliveroo Courier Windsor (8jb. XP, 2016)

The quote above illustrates very simply the complex issues surrounding the gig economy, and food couriers in particular. It highlights that platform food delivery services (PFDS) utilise a body of workers to fulfil deliveries to its customers outlining that the workforce is low paid but also highly motivated by being “less lazy” than the customers.

Background

The ‘gig economy’ is a relatively new phenomenon where the development of technologies has given birth to a unique kind of business model. New corporations have emerged named ‘platforms’ which gather and organise individuals, matching customers with service providers as an intermediary, on a task by task basis (Duggan et al, 2020:np). The individuals offering services are defined as ‘independent workers’ (Manyika et al, 2016:2) and range from people with computer skills writing programmes, crafters making homemade wares and selling them online and those with vehicles transporting people and deliveries.

However, the fact it is a relatively new occurrence means it is hard to gauge how many individuals are involved (Taylor, et al, 2017:25) and the diversity of the workforce makes clarification of their rights and the platforms responsibilities hard to define (Duggan et al, 2020:np). This is where the controversy surrounding independent work is found, in the conflicting reports of the benefits of working independently (Manyika et al, 2016:11) versus the negative aspects of PFDS ‘cutting away’ of workers rights and the self-employed employed shouldering the responsibility for their work alone (McGaughey, 2018:np).

Research focus

The area I will focus on will be food couriers working in the gig economy as the current situation surrounding them as a group of workers is particularly prevalent. There are a growing number of challenges worldwide to the validity of their status as self-employed (Crouch, 2019:21) (Bates et al, 2019:np), claiming the nature of their work is similar to and therefore worthy of the same protections afforded to traditional employees.

The aim of my research will be to add clarity to the debate through the opinions and experiences of the couriers. I will use the reality of their experience to add to the body of research that exists by aligning it with the ideas of Bauman (2005), that we are living in a new precarious reality and gig work is a product of the changing nature of modern life and how individuals are adapting to survive within it.

Research Value

The body of research surrounding the ethical nature of gig work gives a picture of two sides diametrically opposed. Advocates of the gig work suggest the relationship is a win/win situation for the economy, only in need of a small amount of adjustment (Taylor et al, 2017:31), whereas the opposition claim the imbalance of power exposes individual workers to exploitation and should be stopped (Slee:2017). My aim is to identify whether one of these claims has more validity and explore whether there is a way to progress that suits all sides.

The benefit of conducting this research will be to move forward the debate surrounding independent workers. This is a timely topic as the phenomenon is relatively new and the purpose of my study is to highlight a middle ground between the opposite sides of the debate. The use of self-employed individuals by platform companies is a progressive move for the labour economy, and one that many benefit from using (Manyika et al, 2016:11), so calls for it to be made illegal are not an appropriate move forward, what should be focussed on instead is how to balance the system, so the benefits are more equally distributed between the worker and the organisation.

Research Objectives

I have three main aims to my research:

- To evaluate the validity of the classification of couriers as self-employed by assessing the way in which PFDS justify this.

- To examine the reality of working as a food courier, to discover whether there is any truth to either side of the debate. I will assess the extent to which they benefit from the autonomous nature of the work, or feel exploited by the PFDS.

- To identify reasons for the growth in the numbers of independent workers, despite the proposed negative associations.

Methodology

Research question

The conflicting reports of the pros and cons of working as a food courier frames the basis of my research. “Should you Just Eat” is an evaluative investigation into the experiences of the couriers of platform food delivery services (PFDS), to discover whether couriers benefit from working this way or are being exploited by large corporations to increase profits. I aim to discover why couriers work this way despite the disadvantages and what part precarious lifestyles and the desire for less commitment plays in the modern phenomenon of the gig economy.

My research question has undergone alterations since beginning the project, initially, the study started out as a quantitative investigation to evaluate the validity of courier’s classification as a form of customer to PFDS. Since gathering the primary data, the research has evolved to consider why autonomy is so important to working life. I have now included qualitative data gathered through interviewing couriers about their opinions on the benefits and risks of working as a self-employed courier for PFDS and drawn in theories of Bauman’s (2005) ‘Liquid life’ to explain how precarity fits into modern day experiences.

Preliminary research

There are two lines of discourse informing the debate, one centred around the positive effects of the autonomous nature of the work (Taylor et al, 2017:14), and another on the negative, such as a lack of security and stability (Slee, 2016:3). Duggan et al (2020:np) discuss the source of the controversy in the debate “App work relationships are generally not rooted in traditional employee – employer dyads, but rather involve multiple partners contributing to the dynamic exchange agreement”.

Platforms do not produce anything, they act as mediators between groups, in terms of food delivery, the couriers are equal partners, available for hire in exchange for reward in a new ‘sharing economy’ (Slee, 2017:1). Manyika et al (2016:1) argues it is the key point used to support gig work as a positive addition to the global labour market. It is also the crux of the argument against gig work, be it through the challenging the self-employed status of workers as misrepresentation (McGaughey, 2018:np), or the highlighting of the negative aspects of earning a living this way, and whether they outweigh the single positive of being one’s own boss (McGann et al, 2012:np). The controversy forms the basis for my research design, leading me to follow an evaluative path, focussed on the experiences of the individuals working this way and comparing them to that of the food ordering customers.

Design

The research design centred around language used in PFDS business model, and how it ensured couriers were not defined as employees entitled to certain working protections (Ainsworth, 2018:4). Hall (1997:17) discusses representation as the production of the meaning of concepts in our minds and how culturally we share ‘conceptual maps’. PFDS changing the wording of ‘jobs’ and ‘pay’ to ‘delivery opportunity’ and ‘reward’ distances what they are offering from the traditional, conceptual understanding of employment (McGaughey, 2018:np).

To determine the validity of the couriers self-employed status I accessed the sign-up websites of three leading PFDS (Just Eat sign-up, 2020) (Deliveroo sign-up 2020) (UberEats sign-up, 2020). The key words that appear on all three sites are ‘freedom’ and ‘flexibility’, emphasising the autonomy of choosing to work this way. Following this I reviewed the recent adverts of Just-Eat titled ‘magic is real’ (Just Eat advert 2019) and Deliveroo’s ‘Food freedom’ (Deliveroo advert, 2019) and found the concepts of freedom and flexibility also represented there. It was apparent whether an individual technology to access delivery opportunities; or to order food, they would benefit from the freedom and flexibility that was on offer.

As PFDS treat couriers and customers as equal partners in their exchange agreement, by analysing the experiences of both groups I would be able to assess whether their experiences are equitable. In a study similar to mine, regarding crowd workers in the USA, surveys were used by Berg (2016:4) to obtain information and opinions. She gathered quantitative data to analyse the groups demographics and measure their crowd work experience, followed by more detailed questions about work experience and history. In my study I used surveys with fixed response questions and a Likert scale, as surveys with rating scales can be used to establish informants’ views, attitudes or practices (Knight, 2002:93). There are some concerns surrounding the use of Likert scales for statistical tests such as this, as the data produced is ordinal, rather than interval level. However, it is accepted as a useful tool for gauging opinion in the social sciences as they “have the capacity to measure the attitude of the respondent easily” (Subedi, 2016:37).

I designed questionnaires to distribute to couriers at my place of work, and individuals who had a food delivery app on their phone. The aim of the questionnaire was to prove my hypothesis that couriers and customers experience using PDFS differently, and that couriers did not benefit as much from the advertised freedom and flexibility. The numerical data would allow me to perform a t-test in my analysis to provide me with evidence of a difference between the groups (Pagano, 2009:354).

However, once processed through SPSS the results showed the opposite, couriers were satisfied with their experiences. This outcome gave a new perspective to my research, which led me to ask; if couriers experienced freedom and flexibility at work, was that more valuable to them than security and stability? I then decided to follow a mixed methods approach, adding a qualitative element to my project by conducting interviews with food couriers. This is an appropriate course as in many social research projects one set of methods can be used as a prelude to another (Knight, 2002:128). I compiled questions to conduct in semi structured interviews, emulating research done by Schilling et al (2019:np), in which they interviewed youths from different cities around the world about their working precarity to find concepts linking similar themes from the different circumstances.

I conducted interviews with food couriers, and to strengthen the findings I also found video diaries on YouTube (8jb. XP. 2016) of a group of couriers. I analysed the data thematically, looking for statements relating to experience, support for the importance of autonomy and evidence of precarity. The findings of the interviews were interpreted to build a richer understanding of my research, much like Berg (2016:4) who included more detailed open-ended questions to her survey, the interviews offered insight into the nature of working as a food courier and how that fits into a more modern interpretation of employment.

Ethical Considerations

My research sample did not include any vulnerable groups and the risk for participants was small. I included an information sheet outlining that all participants would be anonymous, and that the study was independent and had no affiliation with either their platform or the restaurant in which the surveys took place. Written consent is not required when the survey is anonymous as per the University of Hull’s guidelines, however my interview participants all signed a consent form prior to being interviewed. I identified a potential conflict for couriers that when being asked to fill in the questionnaires they will be engaged in work. To negate this, I designed a brief questionnaire and kept the survey questions short to avoid detaining them for a long time.

Evaluation

The addition of the qualitative element to my research has resulted in a richer body of data. The initial quantitative research could have been stronger, I altered my questionnaires after a pilot showed the questions were too vague. In re-wording the questionnaires to make them more detailed I did lose the element of each group having identical questionnaires but I did ensure they asked the same questions, despite the wording being slightly different.

I discovered when processing the results of the surveys that I had not designed the questions to yield much statistical analysis. I had included a Likert scale that was appropriate for a t-test for comparison of two groups and this has allowed me to reject my hypothesis and the other questions do support the statistical test by showing little difference in the responses. If I were to repeat the research, I would design my questions to produce more interval data so I could perform a more meaningful statistical test.

As a stand-alone piece of research, the surveys would not have allowed me to make any strong claims regarding my project. My sample population was quite small, which leads to problems of generalizability, and would have resulted in any claims-making being easily refuted. However, by recategorising the surveys as investigative research used to build a set of interview questions, this has the result of making the whole body of research more valid. I was pleased to be able to do further qualitative research to strengthen my project, the interviews with couriers shared some common themes so the combining of the initial data with the interview data offers a broader understanding of the situation.

Theme 1 – Customers or Couriers?

Literature

This chapter outlines the initial phase of my research in which I focus on the distinction of couriers as customers by PFDS. Duggan et al (2020:np) describe how it is essential to the business models of PFDS that couriers are classified as another partner in an exchange agreement, along with the purchasing customer and a third-party restaurant, for example, Deliveroo states it offers technology that evaluates the most efficient way of distributing orders based on the location of restaurants, riders and customers (Deliveroo, 2020:np).

Platform companies use technology to distance themselves from the traditional understanding of an employer/employee relationship. Innovators of the model include Uber CEO Travis Kalanick who denied Uber drivers were employees (McGaughey, 2018:np). The provision of an app, along with the autonomy of the worker are the mechanisms they use to justify the self-employed status of the couriers (Duggan et al, 2020:2). The classification of couriers in this way allows businesses to save the costly rigidities associated with employing people.

The vocabulary used by PFDS is carefully designed to ensure couriers are not classed as employed from a legal standpoint, “Uber is an excellent illustration of armies of lawyers contriving documents which simply misrepresent the truth of the rights and obligations on both sides” (Mcgaughey, 2018:np). Tricks include the use of semantics, the branch of linguistics associated with meaning. The word employee comes with certain qualifiers so companies such as Deliveroo substitute employee for ‘riders’ and workers for TaskRabbit are ‘taskers’, by changing the word used for the workers this relieves the company of its legal responsibilities (Mcgaughey, 2018:np). Similarly, the recasting of the employer as a ‘platform’ achieves the same outcome (Crouch, 2019:12).

Despite PFDS efforts to define their workers as self-employed there are legal challenges worldwide (Varghese, 2020:np) claiming independent workers have been misclassified and in fact are employees. Hall (1997:17), in his discussion of systems of representation, describes how we make meaning of objects, people and events of the real world through culturally learned language and concepts, one such concept is the shared understanding of a job in our culture. “Representation enables us to give meaning to the world by constructing a set of equivalences between things, people, objects, events, abstracts ideas” (Hall, 1997:19).

Equivalences between the traditional understanding of an employee and working as a courier include the balance of power in the organisation (Crouch, 2019:17). Clearly PFDS are in a position of authority over couriers, who must submit to surveillance whilst at work (McGaughey 2018:np)(Duggan et al, 2020:np) and are also subject to penalties for underperformance and the possibility of being removed from the platform, which can be likened to disciplinary procedures which apply to employees (Wood et al, 2019:np).

Evidence to show misclassification of couriers, and other gig economy workers is building worldwide (Bates et al, 2109:np), but the very nature of these industries makes it difficult to find a universal solution as the platforms differ greatly and laws are applied on the basis of each country (McGaughey, 2018:np). Surprisingly, despite these legal challenges and lack of protections afforded to independent workers, the number of people working in this way continues to grow (Bates et al, 2019:np) (Schmid-Druner, 2016:7).

The situation of being your own boss is used to explain the attraction to working in this way for the couriers. Manyika (2016:1) proposes a high degree of autonomy in determining their schedules and workload is a defining characteristic of those choosing independent work, while McGann et al (2012:np) states “evidence shows that casualised work can enhance health and well-being through increased sense of autonomy and freedom to negotiate their conditions of work”. However, this often is the only aspect focussed on and critics of PFDS argue there are risks involved for couriers as a result of being self-employed.

The negative consequences of independent work are outlined by Slee (2017:3) as “…removing the protections and assurances won by decades of struggle, by creating a riskier and more precarious forms of low paid work for those who actually work in the sharing economy.” Mcgaughey (2018:np) supports this theory by also choosing to talk about the rights for workers won in the 20th century, and how in the gig economy the tech-corporations priority is to aggressively evade those rights. In this model, the risk of working is entirely placed on the individual, which has the tremendous benefit to PFDS of saving the costs associated with employing someone (Wood et al, 2019:np).

Another strand to the argument against gig work contests the claim of autonomy associated with independent work. Deliveroo state “You’ll be self-employed and free to work to your own availability” (Deliveroo sign-up, 2020:np) and whilst it is true that couriers are under no obligation to work at a specific time, this does not transfer to being able to work whenever they choose. PFDS do not have to control labour costs and, as each courier is paid per ‘gig’ (Churchill et al, 2019:np), it makes sense to have as many couriers as possible to fulfil demand quickly. This results in increased competition for jobs meaning couriers have to work when demand is high, or for longer hours or more days to achieve a sufficient wage to live (Schmid-Druner, 2016:14).

This situation is supported by comments from couriers on Just Eats review page (Indeed, 2020:np) one workers states “Not guaranteed work, too many drivers” while another describes them “Still hiring drivers even when there is not enough work for the existing ones”. A case which embodies the extremes of this is a young man in Russia who died of a heart-attack, suspected to be caused by exhaustion, he collapsed after couriering for ten hours straight (suomeksi, 2019:np). In addition to this McGann et al (2012:np) suggest that any relief from the stress of not being managed by a supervisor is “quickly negated when work patterns are irregular, insecure and job security is questionable”. In undertaking this research, the aim would be to strengthen the argument for independent workers to be classified as full employees, worthy of the protections associated with the status.

Research – Evidence for theory

As highlighted by Duggan et al (2020:np), PFDS class couriers as a partner in their systems, along with the individuals who order and the restaurants who provide the food. The similarities between the groups are that they use an app provided by the company to achieve their outcome, whether that be to deliver or receive food and both groups are free to utilise the service when it suits them. It is therefore logical to class them both as customers of PFDS and so the aim of my research was to discover whether the courier’s experiences were actually equivalent to food ordering customers of PFDS.

I began by qualitatively analysing material on the sign-up sites of three large PFDS to look for common themes throughout, then cross referenced this with advertising material for the same companies. This would give me evidence that PFDS treat the two groups as the same.

Using the example above, it can be seen that the platform uses similar language in their advertising to both groups. Just Eat describe delivering for them as “a flexible opportunity that you can customize to

fit your life style” to potential couriers (image 1). Other key phrases on the website related to flexibility include “choose your schedule and freedom to choose when you work” (Just Eat sign-up, 2020:np). In the same fashion, food ordering customers are encouraged to “Just eat exactly what you feel” and that Just Eat can “summon up your favourite takeaway tonight” in their advert ‘Magic is real’ (Just Eat Advert, 2019:np), also emphasising flexibility for the customer.

Deliveroo advertise “Flexible work, competitive fees” (image 2) on their sign-up page for new couriers, again we see the use of flexibility as key. The website defines couriers as self-employed but links this to being free, working to your own availability and the ability to plan ahead (Deliveroo sign-up, 2020:np). In their Food Freedom television advert, customers are encouraged to “order what you want, where you want, when you want” (Deliveroo advert, 2019).

Uber Eats sign up page succinctly outlines the benefits of couriering as “No boss. Flexible schedule. Quick pay” (image 3), as well as ‘be your own boss’ and ‘work when it suits you’ on their sign-up site (Uber Eats sign-up, 2020:np). Their new advert Uber Eats ‘Bring it’(Uber Eats Advert, 2020:np) promotes the idea that Uber Eats is ‘bringing it’ and that you can bring anything – which links the ability for the customer to eat what suits them with the ability for couriers to work when it suits them.

Research – Survey Design and Distribution

The examples I have chosen demonstrate clear similarities in the approaches used by PFDS to attract both food delivering and food ordering customers. The recurrent words found on all three platforms are that customers will benefit from ‘freedom’ and flexibility’ when using the service. Using this evidence, I created a questionnaire which would assess whether couriers would agree that, as a customer, they do experience freedom and flexibility when they worked. A questionnaire would give me “clear, unambiguous, easy to process and analyse data” (Knight, 2002:50). In order to make a comparative claim I would issue a second round of identical questionnaires to food ordering customers, with the qualifier that they have a food delivery app on their phone.

A concern raised in my ethics submission for this research was that I would be interacting with couriers whilst they would be engaged in work, so I was careful not to make the questionnaire long, allowing me to collect the data I needed in a short space of time. The survey would involve simple fixed response questions, including a Likert scale to gather opinion. I issued the surveys to the couriers whilst I was at work, asking each courier if they would fill one in while waiting for their order to be ready. The surveys were in store for a month, and in that time, I matched the amount of courier questionnaires by asking customers in the shop if they had a food delivery app on their phone.

The responses from the two groups would allow me to make claims regarding whether the two groups had the same experience, as advertised by PFDS. If the results of the survey showed no difference between experiences then this supports claims of PFDS, that couriers do benefit from freedom and flexibility as much as the food ordering customers. However, my research hypothesis was that the responses of the couriers would come back as less positive than the food ordering customers, which I would relate to the problems outlined by those who reject independent work as positive (Slee, T, 2017:3) (Mcgaughey. E, 2018:np) (Duggan et al, 2020:np).

Findings

I will now present the results of the survey questions:

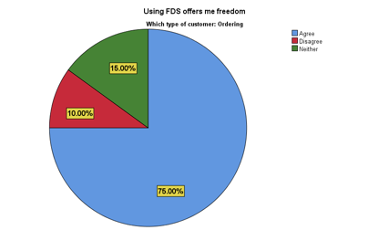

Question 1: Using food delivery services (FDS) offers me freedom in the way I work/ eat

As it can be seen from Figures 1.0 and 1.1 the majority of participants in both groups agree that using FDS offers them freedom, either in the way they work or way they eat. The couriers have a higher percentage with 85%, owing to the fact some food ordering customers were neutral. The second part of this question asked how the participant experienced freedom as a result of using FDS, the most common responses for couriers were ‘flexible hours’ and ‘being my own boss’ whereas from food ordering customers the main aspects were ‘the variety of choice on offer’ and ‘the convenience’.

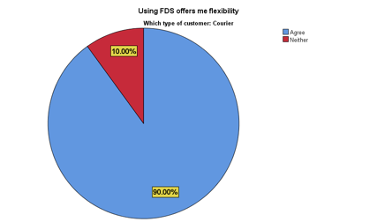

Question 2: Using FDS offers me flexibility

The results for question 2, shown in figures 1.2 and 1.3, were overwhelmingly positive for both groups, only 10% of couriers did not agree that they benefitted from flexibility and only 5% of food ordering customers. The second part of this question, using a Likert scale, asks on a scale of 1-5 how well would you say the flexibility using FDS offers [either to deliver food or to receive food] works for you? The participants were then invited to rate this using the scale of 1 denoting that it does not work at all, to 5, meaning it works very well. I will be using this data to perform a statistical test of significance.

| Descriptive Statistics | ||||||

| Which type of customer | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Courier | How well flexibility works | 20 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 4.4000 | .75394 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 | |||||

| Ordering | How well flexibility works | 20 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.1500 | .87509 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 |

The results in figure 1.4, processed through SPSS, show a mean score of satisfaction for couriers as slightly higher at 4.4 than for food ordering customers at 4.15. Although the results are close its possible to perform a statistical test to assess whether or not the difference between the means is significant and therefore making it possible to accept or reject my hypothesis.

T-test

I will use an independent samples t-test to assess whether the difference between the mean is enough to make a claim that the two groups have a significant variance in the levels of flexibility they experience using food delivery services. The t-test assumes a sample that is normally distributed, so has a normal distribution of population scores (Pagano, 2013:102). The t-test also assumes homogeneity of variance, that the independent variable effects the means of the populations, but not their standard deviations, and that the variances of the two populations are equal (Pagano, 2013:376).

I will be using a two-sample t-test to test the equality of the means of the variable ‘how well the flexibility works for each participant’, for couriers and ordering customers. I will be using a test for independent samples and a 0.05 sig, or the number at which the result will be significant below. This will test whether or not the two independent populations have different mean values on some level. This is also the most appropriate test to use as my sample size is small as “t-test with two samples is commonly used with small sample sizes, testing the difference between the samples when the variances of two normal distributions are not known” (Maverick, 2019:np)

Hypotheses

My null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference between the mean levels of satisfaction of flexibility between couriers and ordering customers using food delivery services.

My alternative hypothesis is that there will be a significant difference between the mean levels of satisfaction of flexibility between couriers and ordering customers using food delivery services.

After running an independent samples t-test the following tables were produced

| Group Statistics | |||||

| Which type of customer | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

| How well flexibility works | Courier | 20 | 4.4000 | .75394 | .16859 |

| Ordering | 20 | 4.1500 | .87509 | .19568 |

I have assumed that there are equal variances in the sample population so in reading the top line of the results table, figure 1.5, it can be seen that there is a sig value of 0.339. This value exceeds our sig. level of 0.05 which means there is not a significant difference between the mean results of the two groups so we must reject the alternative hypothesis.

Question 3: The amount of money I pay / am paid is fair

Question 3 asked participants if, in their opinion, the money that they pay, or are paid is fair, shown in figures 1.6 and 1.7. In both groups 15 out of the 20 participants answered that they agreed with the statement and only 2 of the couriers disagreed, compared with 3 of the food ordering customers.

Question 4: Using food delivery services work well for my lifestyle

Question 4 asked participants how well they felt using FDS worked with their lifestyle with the results shown in figures 1.8 and 1.9. The majority of participants agree that using FDS works well for them, again showing that the courier group is more satisfied, at 18 customers compared with only 14 food ordering. It is also interesting to note that not one of the couriers disagreed with the statement, the two remaining participants in that group stated they neither agreed nor disagreed.

Evaluation of findings

In evaluating the validity of my findings, I can note that my sample size is small, which does affect the generalisability of the results. The sample was intended to be larger as when I began formulating my ideas for the research project the PFDS had recently been introduced at my place of work and it was very popular. I could gather plenty of data as there were so many couriers and groups of them gathered outside the shop waiting for jobs. As my project progressed the popularity of ordering from us decreased, and consequently, so did the number of couriers. In addition to that, the gathering of my data coincided with the quietest time of year at the shop so, if I were to repeat the surveys, I would consider the timing of survey distribution to maximise the numbers of participants I had access to.

A further critique of my survey is that I could have included more statistical tests with my data. In the planning stages I was very focussed on needing to assess the two groups experiences of freedom and flexibility so I asked a basic fixed response question with options to agree, disagree or neither for most of my questions. If I were designing another survey, I would be careful to plan the questions to yield some interval level data, with which I could do further interpretive analysis, rather than descriptive

Conclusion

The results of my findings are conclusive enough to completely reject the research hypothesis and state there is no difference between the experiences of couriers and food ordering customers in terms of the freedom and flexibility when using PFDS. The results of the t-test have statistically analysed the difference between the mean scores of the two groups, in terms of the level of satisfaction they have with the flexibility of PFDS, and found it is not significant. The results of the other questions also support the t-test, showing little difference between the responses of the two groups, in some cases the couriers reporting higher levels of satisfaction than the food ordering customers.

In terms of my study, looking back at the literature which helped me to design my survey, I would have to conclude that as the results show, couriers working for PFDS do benefit from the freedom and flexibility that is promoted as the reason for choosing to work this way. The question regarding fair pay shows that couriers feel the amount they are paid to deliver food is fair and the question regarding lifestyle illustrates that that is a positive aspect of working as a courier, they agree it works well for their lifestyle.

Further research

As this does not align with my research hypothesis, I will use my findings to conduct further research. My results show that couriers feel they benefit from the free and flexible nature of working this way yet the negative aspects of the work are well documented. I will continue my research by investigating why the autonomy of work is prioritised over the benefits of standard working protections. I will consider the effect of platforms and the gig economy on the labour market and the working lives of a generation of workers, the reasons why couriers accept the promise of autonomy, seemingly as a trade off for other working benefits and what part individual circumstances play in the satisfaction levels of food couriers.

Theme 2 – Gig-work and Precarity

In this chapter I will be using Bauman’s (2005) concept of ‘liquid life’ to explain the increase in the phenomenon of independent working. He describes it as life lived under the conditions of constant uncertainty, meaning modern life has lost many of the attributes of security found in the past. In terms of work, the traditional ‘job for life’ or even the concept of regular work has begun to disappear in favour of work which is less secure but also less commitment.

“The need here is to run with all one’s strength just to stay in one place and away from the rubbish bin, where the hindmost are doomed to land” (Bauman, 2005:3).

This illustrates the reality for independent workers, completely responsible for their own security, attained through constant work, chasing jobs and earnings and competing with others in the same circumstance.

I will be using ideas gathered from liquid life theory which match the themes that emerged through the coding of my interviews, these being changes to the working lives of modern individuals, the importance of autonomy and the cruciality of choice in determining one’s identity. I will then link the ideas with further literature that discusses these themes in relation to emerging labour practices, such as gig-work. Throughout I will evidence the themes with real experiences of individual food couriers, which emerged from my interviews and data collected from an online diary of food couriers in Windsor.

Changing Working Lives

In his book, Bauman (2005) outlines the way people work as being transformed, and demonstrates this using the work ethic of highly successful businessman, Bill Gates. Gates is quoted as saying he prefers to position himself “in a network of possibilities, rather than paralysing himself in one particular job” (Bauman, 2005;5), which illustrates the fluid nature of modern employment. In order to be successful, we must flow through life grabbing opportunity as it arrives, yet never staying in one place for long, looseness of attachment and revocability of engagement are the precepts guiding everything.

This example is the perfect analogy for food courier gig work, as individuals are encouraged to access delivery opportunities when it suits them, they can drop in and out of working with ease.

“It’s sold like freedom, and you can come in and out as you please, and its easy, and that was what like, attracted me to it” (Interview 1)

“Yeah……. if I don’t wanna work, I just don’t work” (Interview 2)

The comments above demonstrate a looseness of attachment from the couriers to their work, allowing individuals the freedom to tailor the way they earn to suit their lifestyles and circumstances. While this may seem like progress, there are certain changes to the labour market policies which have led to this position, which are less positive. In his book “Will the gig economy prevail” Crouch (2019:12) notes that the gig economy is seen by many neo-liberal policy makers as an ideal form of work,

“firms can maximise flexibility by calling on and paying self-employed workers only when they need them to perform specific tasks, avoiding the social insurance charges, minimum wage obligations, and the host of other responsibilities that come with so called standard employment”

As a new generation of workers are exposed to the labour market they are faced with a very different set of prospects to their fathers before them. Holmes and Mayhew (2012:np) outline, there has been a polarisation of available work characterised by an increase high and low wage jobs and the disappearance of middle-income roles. In addition, higher levels of educational attainment exacerbate the problem with increased competition for higher paid roles (Holmes & Mayhew, 2012:np). Young people are finding they have to be creative to find ways to succeed in a saturated labour market, so identifying and seizing opportunity is key.

“I take enough career risks being paid to cycle round all day” (Interview 3)

“especially just being 18 and still working another job” (Interview 1)

The first comment above shows an awareness from the participant that they are in a precarious situation, by referring to their choice to courier as ‘risky’. The second comment demonstrates determination, utilising opportunity and working hard to earn their living as the work they have chosen is low paid.

When seeing an increase in low-status roles there arises a question around the dignity individuals gain from their working lives and how this affects people in these roles. Organisations can increase social inequalities through their structure of hierarchy, dignity can be attached to higher status jobs and denied from others (Avent-holt & Tomaskovic-Devey:2019:np).

“The denial of dignity is a particular tool used as a moral justification to legitimate closure (of certain roles) and exploitation (in terms of wages) forced on lower status human beings.” (Avent-holt & Tomaskovic-Devey:2019:np)

In removing the employment status of gig workers from an organisation there is a lack of recognition of their contribution to that company, and in the denial of standard workers’ rights a lack of recognition of their place in society.

In response to these circumstances, when discussing ‘urban youth tactics’ Schilling et al (2019:np) identified processes of ‘detaching’ and ‘gathering’ to negate this loss of dignity. These involve individuals making distance between their current conditions and their future aspirations and gathering together to make solutions,

“More than anything what I’ve learned when I cycle is that the purpose of life is to move forward under your own efforts, as figuratively, as literally as possible” (Interview 3)

This courier comment demonstrates detachment as it reveals a high level of satisfaction with his work under his own efforts, evidently, he views the work as a worthwhile contribution to his career journey rather than an undignified stop gap.

“They had a Facebook group that they created…..and from that they were like okay, we’ll bring you into this” (Interview 1)

“Yeah, it did make you feel less alone when you could talk to the other drivers” (Interview 1)

“we do meet up and we chat everyday…..we chat about jobs and stuff, and money, its always money” (Interview 3)

“so, one of the things that makes me laugh more than anything else is the WhatsApp chat we have for the riders” (Interview 3 / 10)

The concept of gathering was evident from all three couriers who spoke of community and support through a network of couriers for various reasons, mainly due to a lack of input or inability to connect with their respective PFDS.

Autonomy

The importance of autonomy has been evident throughout this investigation, in my surveys, interviews and in the literature on gig-work. Bauman (2005:5) states those that are the most successful in modern liquid life have “the freedom to move, freedom to choose, freedom to stop being what one already is and freedom to become what one is not yet”. Liquid life means no commitment or expectation from either party, but the situation has its consequences which are apparent in the precarious working environment of couriers. PFDS treat the benefit of autonomy as a fair trade for a lack of employment protections. This fact is explicit in the communications to potential couriers and understood by individuals already engaged in gig work.

“I understood [about the lack of employment protections] cos I had a friend that was already working as a driver…he told me that we weren’t entitled to sick pay, holiday pay…and I was kind of used to that, being on zero hours contracts” (Interview 1)

“Yeah, it was plainly stated you work for yourself” (Interview 2)

The gig economy business model presents all participants as equal ‘partners’ in an exchange of goods and services, equally free to engage, with no hierarchical implications (Crouch, 2019:19). Individual worker’s benefit from freedom of choice but also freedom from being watched by someone above them.

In his book “Collateral Damage” Bauman (2011:166) explains how ‘the manager’ rose to prominence in the late 1930’s as owners of business hired middlemen to organise sloppy, unwilling and resentful labourers, but he sees managers as the ones with the real power. This created a contentious relationship, where the employees resent the authority of the manager and the manager is suspicious that the employees will do all they can to evade working. This means the chance to escape this dynamic is highly attractive to workers,

“I really liked that freedom, you didn’t have a boss over your shoulder” (Interview 1)

“..in one way its good because you don’t have a boss” (Interview 2)

“One of the main things that’s different is you don’t have a boss, so you haven’t got anyone sort of hovering over, telling you what to do all the time” (Interview 3)

It’s clear from the above comments these individuals see bosses as a negative aspect of traditional employment, they cite being able to decide their own work schedules as one reason but also the ability to relax, ‘chill’ whilst working and not feel as though they are being ‘loomed over’ and judged by how hard they are working.

This change in management practice is due to the development of technologies, computer algorithms; programmed to organise workers in the most efficient manner and the instructions passed on to employees through an app (Duggan et al, 2020:np). These advances, along with the self-employed status of couriers, mean the platforms require only small amounts of human management.

“when I went to my sign up and went through all the processes, I was really surprised about how small the department is” (Interview 1)

“In London I think there are only two (registration offices) and the have about 5-10 people in them” (Interview 1)

This allows the independence employees crave and benefits the company through massive savings in employment cost. “[The managers] refused to manage, instead, they now demand that the residents, on the threat of eviction, self-manage” (Bauman, 2011:168), this quote refers to new management approaches within companies. Employees are forced to compete for jobs, with the task going to the most innovative and creative employees, but can also be extended to cover PFDS models that have removed the managers completely and push the responsibility for working on to the individual.

The management of one’s own success is something that workers appear to be becoming accustomed to. In Schilling’s (2019:np) research he identifies that the conventional understandings of work no longer exist and describes that “young urbanites everywhere must weave their existence” through the circumstances of instability. His research identified individuals shunning the traditional routes of education leading to employment, instead using lower paid work as a stepping stone to access opportunities and network with others.

This is reinforced with the work of Plum & Knies (2019:np) who analysed employment data and found that the future unemployment risk is lower for those on low pay than those currently unemployed, and also those in low paid work have more chance of becoming higher paid than the unemployed. This supports they claim that engaging in low paid work can be used to facilitate moving on to other jobs. They state this practice lessens an individual’s “human capital depreciation” by signalling a willingness to work to potential employers (Plum & Knies:2019:np). Their work evidences that couriers and other gig workers are using autonomy to actively improve their future work chances in an uncertain work environment, rather that settling for work with no prospects.

The autonomous nature of gig work means that individuals have greater control of how their work forms their identity. Farrugia (2019:np) addresses the issues of identity through the lens of Post-Fordism “where precarity and un/underemployment are normalised while the requirement for young people to seek subjectivity through work is intensified”. He notes that workers now use self-reflexivity as a tool to navigate uncertainty by aligning their self-worth with the ability to add value through their work and investing themselves more fully. The following quote illustrates this concept by showing the individuals commitment to his work, reflecting that it makes him an athlete,

“some people may think this job is for people who are unambitious, or that this job is like any other dead-end career, but if cycling 200 miles plus a week and getting paid to do it doesn’t make you an athlete, I’d like to know what does?” (Interview 3)

In considering the importance of complete autonomy, it is interesting to note that all three interviewees lamented the lack of human interaction at some point. This signals that although they value the freedom of working unsupervised, they still feel a need for support in some aspects of their work as in traditional employment.

“the issues arose there when there wasn’t anyone to talk to as the offices were only open for a short amount of time.” (Interview 1)

“no, it is a bit bad this but there’s no way, apart from messaging through the app, to contact Uber, unless you have a live order, or you are a customer with a live order. There’s no one to directly speak to over the phone” (Interview 2)

“Why don’t you call the support, say they are not answering and then wait for them to sort it out?” – “Nah, it takes 15 minutes to get anyone on there” (Interview 3 – screen conversation between two couriers)

Issues the couriers spoke about needing support for ranged from help sorting out problems with deliveries, mediation between themselves and restaurants and calling in sick. More serious safeguarding issues included injury whilst working, damage or theft of vehicles, and reporting other drivers who they knew were working without the proper insurances, issues where they felt their safety at work was compromised. One story which stood out was of a rider whose bike was stolen and then used later on to steal people’s mobile phones,

“…the police came to him, interviewed him, sat him down and was like, well this isn’t me, I reported it as stolen, this happened while I was on shift. He relayed it to Deliveroo and they weren’t able to help out with it, they weren’t saying ok we can help you with this… its almost like ok, you are working for us but you need to defend yourself” (Interview 1)

The PFDS input into the situations they create is absolutely at a minimum and they ensure that there is no way to be involved through the barrier created by the technology, creating the precarious work environment for their couriers.

The Cruciality of Choice

In liquid life, Bauman (2005:3) highlights the successful as being those “to whom space matters little and distance is not a bother, people at home in many places but in no one place in particular”. This creates the image of a person who can move around freely to take opportunity where it may arise, but in order to do this an individual must have the right circumstances. He also describes a second group, to whom playing the game is not a choice; “flitting between flowers in search of the most fragrant is not their option, they are stuck to a place where flowers, fragrant or not, are rare (Bauman, 2005:5). This is where the phenomenon of gig work can be broken down to understand why it has conflicting reports of successes for some and misery for others.

Individual circumstances dictate the quality of experience for independent workers, a concept outlined in detail in a report by the Mckinsey Global Institute. For their paper Independent Work: Choice, Necessity and the Gig Economy, Manyika et al (2016:7) surveyed more than 8000 independent workers in six different countries. They categorised participants based on two criteria; firstly, whether working independently was their primary source of income or a secondary supplemental one. The second aspect distinguished between those who elect to work independently and those who are independent out of economic necessity.

In using these criteria Manyika et al (2016:7) identified workers as being in one of four categories which can be seen in the figure 2.1.

The findings were that the majority of participants reported satisfaction with independent work, this was made up of the two groups whose preferred choice it was to work independently, the ‘Free Agents’ making up 40% and the ‘Casual Earners’ with 30%. This showed that whether the participant was using independent work as their primary or secondary income, it is the element of choice that defines their satisfaction with it. These two groups are more engaged in their work, relish the opportunity to be their own boss, enjoyed dictating their own hours and were happy with their overall level of income (Manyika et al, 2016:10).

For the remaining 30%, those in the ‘Reluctant’ or ‘Financially Trapped’ categories would rather be engaged in traditional or higher paid employment but their circumstances dictate they must use independent work to support themselves. However, the fact they are the minority should not be discounted, they still represent a significant number of workers, and improving the opportunities and income security for these groups could have a positive effect on their satisfaction levels (Manyika et al, 2016:10).

In considering my interview participants through the categories set out by Manyika et al (2016), I believe two of them to be ‘Free Agents’ and one to be a ‘Casual Earner’ as for two of them it is their primary income and one it is secondary, and all three mention they chose to work as a food courier. One aspect I feel is worthy of highlighting is in two of the cases the choice to work as food courier is centred around the cycling element of the job, in particular the risky, adrenaline fuelled competitive nature of the work. This illuminates a subset of couriers who take the job very seriously, they like the bikes, they like the kit and they enjoy the exercise they are being paid to do,

“I just quite enjoy the freedom of just gunning around and delivering food and I just like cycling a lot, and it’s an excuse to spend money on my bike” (Interview 3)

“I think the main thing that draws me in is the fact that you get to cycle and exercise whilst your working, its great” (Interview 3)

There is also an element of competition between couriers, who get a kick out of racing around trying to get to jobs as fast as possible and comparing the amount of jobs they have done to other riders.

“its not the same as having a black box in your car so speed limits and that kind of stuff doesn’t count the same, its like in a Spiderman movie when he’s not gonna make it in time, changes into the Spiderman outfit and starts swinging around to get there quicker, it was kinda the same….. I wanna get as many as I can in one night” (Interview 1)

“This competitiveness is something only a few of us share, bit I think it’s those riders that have the most fun in the job, personally” (Interview 3)

These passages show that the couriers are indeed benefitting from the freedom of choice to work this way, they are demonstrating that they are capable of managing themselves to increase their own productivity independently and actively pushing themselves harder to achieve more. The element of risk is what may make this a more exciting way to earn money and would not be possible in a traditional job as the workers would be supervised and prevented from putting themselves at risk.

“although it isn’t safe and it isn’t smart there’s nothing to stop you, there’s nothing to tell you otherwise” (Interview 1)

“I get a lot of satisfaction from pushing myself to make marginal gains, knowing they add up over time and the adrenaline you get from taking risks involving speed gives me energy all night, and that’s valuable.” (Interview 3)

This subset of couriers is the most aligned with Bauman’s (2005:4) theory of liquid life, as he describes those who benefit the most from precarity as “living in a society of volatile values, carefree about the future, egoistic and hedonistic”. The participants in my study who engage with competitive gig working seemed to be carefree, using the method of earning to enrich their lives, not only with the extra cash they gained from pushing themselves to do more deliveries but from the freedom of being supervised, they also wanted to play and chill with their friends and it was their decision which one they did.

Conclusion

In order to conclude this study, I will now revisit my research objectives with the aim of matching them up with my findings and outlining what conclusions can be drawn as a result. The purpose of my research was to investigate the reality of working as a food courier in the gig economy and clarify some of the issues surrounding the pros and cons of working in this way. I will make some recommendations about what could be done to address the issues highlighted as a result of my research.

Research Objectives

- To evaluate the validity of the classification of couriers as self-employed by assessing the way in which PFDS justify this.

In order to achieve this, I analysed through the literature the way in which PFDS use their business model to classify couriers as ‘equal partners’ in an exchange with themselves and the people who order goods and services. There is no evidence to suggest the PFDS trick couriers into working for them, the sign-up processes clearly state that workers are self-employed. PFDS advertise to potential couriers and customers that they will benefit from the ‘freedom’ and ‘flexibility’ of the service. My surveys confirmed that this is the case, with couriers in some cases reporting higher levels of satisfaction with PFDS than the ordering customers.

The fact that couriers report benefitting from the autonomy of working this way gives weight to the view that independent work can be a positive method with which to earn a living. The results of the survey revealed couriers value choosing their own hours and being their own boss, which suggests that the classification is valid, and revoking the status to become employees of PFDS is not a desired course of action.

- To examine the reality of working as a food courier, to discover whether there is any truth to either side of the debate. I will assess the extent to which they benefit from the autonomous nature of the work, or feel exploited by the PFDS.

I assessed through my interviews that couriers are fully aware of the pros and cons of working as a food courier. The participants spoke positively about the freedom to manage their own schedules and not being monitored whist working. They demonstrated they were aware they did not qualify for many of the usual benefits of traditional employment but did not express anger or frustration about the situation, rather a simple acceptance, which suggests they appreciate the looseness of the connection with the PFDS.

The issues the participants revealed they struggled with tended to revolve around having support to deal with issues that arose through working and general safeguarding issues. This led me to conclude more could be done by PFDS to improve the experience for couriers, without effecting the self-employed status. It should be recognised that there are issues and risks that arise as a result of working as a courier and some of that should be shared by the PFDS, they should be easier to contact and offer more support with mediation between partners and in issues affecting courier’s personal safety.

- To identify reasons for the growth in the numbers of independent workers, despite the proposed negative associations.

By matching themes that emerged from interviewing food couriers with elements of Bauman’s (2005) ‘liquid life’ theory, I was able to explain some of the questions regarding the increase in the phenomenon of independent work. Ideas surrounding changes in modern life towards a state of precarity included changing working lives, the increased importance of autonomy and the cruciality of choice.

These links may explain some of the positive aspects of independent work yet, even if we recognise it as an important addition to today’s labour market, there is no reason other than cost saving for the PFDS, why it should come to the exclusion of any employment protections for the workers. The idea that autonomy is a fair trade for employment protections is one promoted by the innovators of independent work and is the key factor to address in order to allow its continuance whilst making it a fairer for the individual workers.

Recommendations

It is clear that couriers value the freedom and looseness of attachment that their self-employed status allows them, therefore, I would not recommend that the way forward would be to campaign for gig work to be re-imagined as a form of traditional employment. As a result of my research I propose that independent work as a way to earn a living can be a positive addition to people’s lives, but it does need some adjustment to make it safer and fairer for the workers.

My first proposal would be to campaign to force PFDS to offer more support to couriers with the addition of a 24-hour contact service. This would make PFDS more accountable to assist couriers with issues that arose as a result of their work, either with the other partners in the system or individual problems the couriers had with their health and safety. The couriers are self-employed but the PFDS are the reason they are out working so having to provide support for the couriers would balance the risk previously shouldered by the couriers alone.

Secondly, I would propose increasing financial protections through a policy change to the benefits system. The government currently supports worker on low incomes through tax credits, this is in recognition that some companies pay low wages, which the government then tops up. The system for self-employed gig workers excludes them from many benefits, including minimum wage requirements and this means some are forced to work long hours to make ends meet. If the tax credits system was altered to include this group of workers, paying them a top up to their earnings it would remove some of the pressure associated with the precarious nature of working as a courier.

Another proposal which would have a positive effect on the lives of gig workers would be the introduction of the Universal Basic Income, which would provide everyone with a standard wage from the government. Advocates of the radical proposal argue that the knowledge of a steady wage would allow individuals to pursue entrepreneurial avenues (Lehdonvirta, 2017:np), which gig work is already a part of, allowing people further freedom to build their own work/life balance.

Reflection

In undertaking this research, I have been surprised by some of the results. I started this project believing that food couriers were a disadvantaged group of workers, exploited by greedy corporations, and in need of recognition of a proper employment status. What I have learned along the way is that the labour market, and people’s lifestyles in general are changing, and gig work is just one of the ways this is apparent, in the changing way people are earning their living.

Whilst I do not support the idea that autonomy at work is a fair swap for employment protection, I now realise that freedom to choose when and how one works is a valuable aspect to employment. The addition of some protections to the workforce would open up this new form of employment to more people without exposing them to unnecessary risk, which could be the proposed win/win situation for everyone.

I have a new respect for all those involved in social research, in reading a paper it is not apparent the volume of work involved. If I were to repeat this project, or undertake to do more research, I would definitely dedicate more time to planning at the start of the process to make the study run more smoothly. I am now aware of how crucial timing is to gathering research data to ensure enough is obtained and increase the relevance of the findings. I would also be interested in furthering this research by broadening the study to include more couriers from different circumstances and looking into the demographics to see which groups are most vulnerable.

Bibliography

8jb, X. P. (2016) Deliveroo windsor autumn. Available online: https://youtu.be/iLcw9Wa1TBs .

Ainsworth, J., (2018), Gig economy: Legal status of gig economy workers and working practices. House of Lords Library, [Accessed: 13-04-2020].

Avent-Holt, D. & Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2019) Organizations as the building blocks of social inequalities. Sociology Compass, 13 (2), e12655. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12655

Bates, L. K., Zwick, A., Spicer, Z., Kerzhner, T., Kim, A. J., Baber, A., Green, J. W. & moulden, d. t. (2019) Gigs, side hustles, freelance: What work means in the platform economy city/ blight or remedy: Understanding ridehailing’s role in the precarious “Gig economy”/ labour, gender and making rent with airbnb/ the gentrification of ‘Sharing’: From bandit cab to ride share tech/ the ‘Sharing economy’? precarious labor in neoliberal cities/ where is economic development in the platform city?/ shared economy: WeWork or we work together. Planning Theory & Practice, 20 (3), 423-446. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1629197

Bauman, Z. (2011) Collateral damage : Social inequalities in a global age. Cambridge: Polity.

Bauman, Z. (2005) Liquid life. Cambridge: Polity.

Berg., J. (2016) Income security in the on demand economy: Findings and policy lessons from a survey of crowdworkers. International Labour Office, . https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Janine_Berg/publication/296638565_Income_security_in_the_on-demand_economy_Findings_and_policy_lessons_from_a_survey_of_crowdworkers/links/56d705fb08aebe4638af14a3.pdf

Churchill, B., Ravn, S. & Craig, L. (2019) Gendered and generational inequalities in the gig economy era. Journal of Sociology, 55 (4), 627-636. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319893754

Crouch, C. (2019) Will the gig economy prevail?. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Deliveroo (2020) About us – deliveroo. Available online: https://deliveroo.co.uk/about-us [Accessed 13-04- 2019].

Deliveroo advert (2019) Food freedom. Available online: https://youtu.be/o2HaQEH6MPo [Accessed 06/02/20.

Deliveroo sign up (2020) Deliveroo – ride with us. Available online: https://deliveroo.co.uk/apply [Accessed 08/03/ 2020].

Duggan, J., Sherman, U., Carbery, R. & McDonnell, A. (2020) Algorithmic management and app-work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and HRM. Human Resource Management Journal, 30 (1), 114-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12258

Farrugia, D. (2019) How youth become workers: Identity, inequality and the post-fordist self. Journal of Sociology, 55 (4), 708-723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319865028

Hall, S. & Open University (1997) Representation : Cultural representations and signifying practices. London ;Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage in association with the Open University.

Holmes, C. and Mayhew, K., (2012), The changing shape of the UK job market and its implications for the bottom half of earners. Resolution Foundation, Available online: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2014/08/The-Changing-Shape-of-the-UK-Job-Market.pdf [Accessed: 2019].

Indeed (2020) Just eat employee reviews. Available online: https://www.indeed.co.uk/cmp/Just-Eat/reviews[Accessed 06/02/20.

James Manyika, Susan Lund, Jacques Bughin, Kelsey Robinson, Jan Mischke and Deepa Mahajan, (2016), Independent work: Choice, necessity and the gig economy. McKinsey Global Institute, Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/Employment%20and%20Growth/Independent%20work%20Choice%20necessity%20and%20the%20gig%20economy/Independent-Work-Choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy-Full-report.ashx .

Just Eat advert (2019) Magic is real. Available online: https://youtu.be/78OtNSzsRzQ [Accessed 06/02/20.

Just Eat sign-up (2020) Apply to be a delivery driver/food courier. Available online: https://couriers.just-eat.co.uk/application [Accessed 08/03/ 2020].

Knight., P. T. (2002) Small-scale research. London: Sage Publications.

Lehdonvirta., V. (2017) Can universal basic income counter the ill effects of the GiG economy? Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/money/can-universal-basic-income-counter-the-ill-effects-of-the-gig-economy-a7681761.html [Accessed 14/04/ 2020].

Maverick., J. B. (2019) What assumptions are made when conducting a t-test. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/073115/what-assumptions-are-made-when-conducting-ttest.asp[Accessed 14/04. 2019].

McGann, M., Moss, J. & White, K. (2012) Health, freedom and work in rural victoria: The impact of labour market casualisation on health and wellbeing. eContent Management Pty Ltd. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2012-18257-009&site=ehost-live

McGaughey, E. (2018) Taylorooism: When network technology meets corporate power. Industrial Relations Journal, 49 (5-6), 459-472. https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12228

Pagano, R. R. (2009) Understanding statistics in the behavioural sciences, 9th edition. Canada: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Pagano, R. R. (2013) Understanding statistics in the behavioral sciences, 10th , international edition Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Plum, A. & Knies, G. (2019) Local unemployment changes the springboard effect of low pay: Evidence from england. Plos One, 14 (11), e0224290. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224290

Schilling, H., Blokland, T. & Simone, A. (2019) Working precarity: Urban youth tactics to make livelihoods in instable conditions in abidjan, athens, berlin and jakarta. The Sociological Review, 67 (6), 1333-1349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119858209

Schmid-Druner, M., (2016), The situation of workers in the collaborative economy. European Parliament – Employment and Social Affairs, Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2016/587316/IPOL_IDA(2016)587316_EN.pdf .

Slee, T. (2017) What’s yours is mine : Against the sharing economy. La Vergne: OR Books.

Subedi., B. P. (2016) Using likert type data in social science research: Confusion, issues, and challenges. International Journal of Contemporary Applied Sciences, 2 (2), 36-49. http://www.ijcar.net/assets/pdf/Vol3-No2-February2016/02.pdf

suomeksi (2019) Terrible news from russia. Available online: https://www.justice4couriers.fi/2019/05/01/terrible-news-from-russia/ [Accessed 18/02/ 2020].

Taylor., M., Marsh. G, N. D. and Broadbent., P., (2017), Good work: The taylor review of modern working practices. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/627671/good-work-taylor-review-modern-working-practices-rg.pdf [Accessed: 08/03/2020].

Uber Eats advert (2020) Bring it – uber eats. Available online: https://youtu.be/-1tayzQn8uY [Accessed 08/03/ 2020].

Uber Eats sign-up (2020) Deliver with uber eats in the UK. Available online: https://www.uber.com/gb/en/drive/delivery/ [Accessed 08/03/ 2020].

Varghese, S. (2020) GIG economy workers have a new weapon in the fight against uber. Available online: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/gig-economy-uber-unions [Accessed 18/02/ 2020].

Wood, A. J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V. & Hjorth, I. (2019) Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy. Work, Employment and Society, 33 (1), 56-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018785616.