Abstract

This essay examines the issue of censorship within social media, and how this can promote attitudes of hegemonic masculinity. The literature review explores four different groups of women; those who menstruate, sex workers, fat women and LGBTQ+ women, and how each group is individually oppressed by overt or covert censorship. Thought is then given as to how this could encourage ideals of hegemonic masculinity. Relevant literature is used within this piece to strengthen this argument. Primary data was also collected via a questionnaire to assess the attitudes of the general public towards censorship in terms of the kind of content they deemed to be appropriate for general online viewing. The aim of this was to create more evidence in the form of statistics to strengthen the argument further. However, the results of the questionnaire were not as expected – the differing opinions between acceptable or not acceptable were fairly balanced, even between genders. Therefore, it was made clear within this research that there must be extraneous factors which influence the censorship of women online. It could be concluded, overall, that more strenuous methods of research should be used – covering more possible factors, and with questions that could be analysed more deeply.

Author: Emma Louise Hewison, April 2020

BA (Hons) Sociology

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Overt Censorship

- 3 Covert Censorhsip

- 4 Results and Methods

- 5 Conclusion

- Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I’d like to give special thanks to Georgina Kelly, whose proofreading skills and endless words of encouragement ensured I made it to the end of this dissertation. Love you Gina!

Also to Dr Mick Wilkinson, who was a brilliant supervisor even during a global pandemic. Thank you, Mick.

1 Introduction

Since the beginning of humanity, women have been viewed as the weaker sex. The argument being that Eve was said to be born from Adam’s own flesh, thus making women subservient to men. Prior to the first wave of Feminism (around the 19th Century), women were the property of their husbands or fathers; they could not keep their own bank accounts, own properties, or vote. Women had no choice but to submit to their husbands and personify the ideal wife and mother, as there was little to no provision for them to do otherwise. This led to the idea that “women are not powerless because they are feminine; they are feminine because they are powerless.” (Hekman, 1999; 84). The late 19th Century marked the first wave of the Feminist movement – by way of the Suffragettes. This is what most people envision when they think of traditional Feminism; however the second and third waves (1960s and 1990s, respectively) were also important in their own time.

One of the most famous traditional Feminists, Ann Oakley, looked deeply into the physical differences between genders, and whether their mental differences were a result of their gender compared to their social interactions. She found that “to be a man or woman, boy or girl, is as much a function of dress, gesture, occupation, social network and personality as it is of possessing a particular set of genitals.” (Oakley, 1972; 158). This suggested for the first time that males and females were not so biologically different as people first thought. They were simply brought up differently and allowed to dress differently and enjoy different things. She discovered that girls have more freedom to explore intersex roles than boys: “a boy’s deviation is ‘sissy’ whereas a girl is merely ‘a tomboy’ – a phase she will easily grow out of when she needs to.” (Oakley, 1972; 179). However, in the same regard, little girls were usually dressed in pretty frilly clothes, completely unfit for any tomboyish activities. At such an early age, this is the sort of conditioning which so harshly separates the genders. As a result of this, young girls were forced to grow inside a constricting mould which is primarily associated with femininity, and young boys were led in the opposite direction.

In the present day, the factors which cause gender inequality have multiplied inexplicably, through the conception of the Internet. Within the past two decades, social media has become a dominant form of communication and networking for the general public. In 2019, “2.8 billion people were using at least one of [Facebook’s] core products (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram or Messenger) each month.” (Clement, 2019, np). Since the birth of social media type websites such as Facebook (in the early 2000s), the concept of social networking has grown exponentially, and transformed into something completely unrecognisable from what it once was. In young people especially, social media has a very prominent presence in the lives of many. Not only a method of communication, but a way of narrating one’s own life, a person’s social media account is a glimpse into how they portray themselves and how they perceive the world around them.

In order to ensure that such a widely used source of information and communication is safe for its users, certain measures have been implemented by the government and enforced by online regulators. For example, censorship; defined here as the removal or prohibition of content that is considered inappropriate. This helps to ensure that the Internet is a safe and accessible place. For example, popular social media website Twitter does not take any form of extremism lightly: “we will immediately and permanently suspend any account that we determine to be in violation of this policy.” (Twitter, 2019, np). This means that any person thought to be spreading terrorist ideas, radicalising others, or in any way targeting another person, will be sanctioned accordingly. There seems, however, to be a change in this safeguarding policy when it comes to gender differences.

People have been known to post every aspect of their lives across social media platforms, including things that are very personal. This can include pictures of their bodies – or their children’s bodies – sometimes (intentionally or unintentionally) in a risqué fashion. The discrepancy here is that there seems to be different standards of what is deemed appropriate for general viewing, between men and women. For example, the social media platform Instagram will allow users to post a topless picture of a man, but not of a woman. The female breast is considered by Instagram officials to be a thing which is obscene, inappropriate for the public eye. A fitting comment was made by Price and Shildrick (1999; 12): “the body, then, has become the site of intense inquiry, not in the hope of recovering an authentic female body unburdened of patriarchal assumptions, but in full acknowledgement of the multiple and fluid possibilities of differential embodiment.”

Feminist researchers employ a uniquely Feminist method. This is, by basic definition, a way of investigating social injustice using Feminist theories – i.e. conducting their research and analysing their results through the lens of female oppression. This can help to establish new social facts, for example, a study by Eisenberg and Micklow (1974) helped to establish wife battering as a social fact, by including statistics such as that in 16,000 initiated annual divorces, 80% of women reported being beaten by their husbands (Reinharz, 1992;82). Social facts such as this can help bring to light issues within women’s lived experiences, and helps them to come forward and have their issues defined as actual crimes.

This essay will explore new issues of oppression that women have had to face as a result of social media in light of feminist theory. It will provide examples of the female body being subject to censorship and how this promotes attitudes of hegemonic masculinity – defined here as the dominant male characteristics in society. This will be done through assessing the impact of two types of censorship. Overt censorship is defined as “done or shown openly; plainly apparent.” Covert censorship is defined as “not openly acknowleged of displayed.” (Google Dictionary, 2020). The opinions of the general public will also be used via a short questionnaire, to consider what they perceive to be appropriate for general online viewing. Their responses will be analysed to consider whether the overall opinion of this group promotes attitudes of hegemonic masculinity.

2 Overt Censorship

2.1 Menstruation

Having established the theoretical basis underpinning the concept of this essay, it is important to contextualise this in relation to modern day examples of the struggle which women face against censorship in online social media. This struggle can take many forms, some blatantly obvious and some much more covert. In more overt instances of censorship, public outrage can be caused. An example of this is Rupi Kaur’s battle with Instagram over an image of a menstruating woman, depicted in this case study.

Rupi Kaur is a New York Times bestselling writer and illustrator from Punjab. Through her work, Kaur produces raw and honest depictions of the hidden feelings and issues in society – in a manner that she refers to as depicting “love, loss, trauma, healing, femininity, migration, [and] revolution.” (Kaur, 2017; np). Whilst best known for her poetry, in this instance reference is paid to a series of images she took for a university project in 2015 – aimed at explaining taboo subjects using no words. On posting an image from this photo series on Instagram (depicting a woman lying in bed, fully clothed, with menstrual blood on her trousers and bedding), the content was removed from Instagram multiple times. Initially, Kaur re-posted the image – believing its removal to be a mistake – but soon realised that Instagram was censoring her image due to apparent violation of their community guidelines. The reason provided for this was that the photo included nudity or sexual content (which, it should be emphasised here, it did not). On a literal interpretation, the image itself fails to violate any of Instagram’s guidelines.

Outraged, Kaur re-posted the image a third time, with a scathing caption questioning the integrity of Instagram’s guidelines and the consistency with which they are applied:

“thank you @instagram for providing me with the exact response my work was created to critique. you deleted a photo of a woman who is fully covered and menstruating stating that it goes against community guidelines when your guidelines outline that it is nothing but acceptable. the girl is fully clothed. the photo is mine. it is not attacking a certain group. nor is it spam. and because it does not break those guidelines i will repost it again. I will not apologize for not feeding the ego and pride of misogynist society that will have my body in an underwear but not be okay with a small leak. when your pages are filled with countless photos/accounts where women (so many who are underage) are objectified. pornified. and treated less than human. thank you.”

(Kaur, 2015, Instagram post; my emphasis)

The idea that society will “have [her] body in an underwear” is a direct criticism of the way female nudity only seems to be acceptable in a way that is pleasing to men. This is because “women provide heterosexual men with sexual validation, and men compete with each other for this.” (Donaldson, 1993; np). Two traditional characteristics of hegemonic masculinity are demonstrated here: that males are sexually dominant, and that they are competitive. Therefore, if a woman encourages these ideas by posting tastefully suggestive pictures in her underwear, this is more likely to go undetected than something which does not appeal to men at all – such as menstruation. Kaur also mentions here that many of the girls in such suggestive photographs are underage – yet this issue does not seem to have been addressed other than warning against it. This is all Instagram have to say on the matter “We have zero tolerance when it comes to sharing sexual content involving minors.” (Instagram Community Guidelines, 2020, np). Arguably, this is a far more serious issue than a blood stain on a bed sheet.

It is also significant to note the fact that Rupi Kaur has a very large Instagram following (3.9 million as of 14/03/20). To censor someone with such a large fan base creates (whether intentionally or unintentionally) a very widespread message of what is and is not acceptable on social media. In essence, this case informs the world that periods are dirty and women should keep them private. Instagram does not want to see them. Carfolla (2015) explained this process of concealment works to “filter out our bodies and […] create an image of women that is unrealistic and unattainable.” (Lese, 2016; 52); thereby fundamentally changing how women view their bodies. If periods are not shown in the public eye, then anyone who challenges this – even accidentally – risks being viewed as unclean, and thus not fitting in with the idealistic picture painted by influencers and celebrities (imagine the headlines if, for example, Beyoncé was photographed on the red carpet with her period leaking onto her dress?). This is therefore a prime example of women being rendered invisible by social media. The only reason that any action was taken to rectify Kaur’s experience, in this case, was the support of her large following; if a person does not have this, it is likely that nothing would be done at all, and their experiences will remain invisible.

The unpredictability of the female body undoubtedly sets women apart from men. As emphasised by commentators like Price and Shildrick (1999; 2), “whilst all such marginalised bodies are potentially unsettling, what it at issue for women specifically is that, supposedly, the female body is intrinsically unpredictable, leaky and disruptive.” A characteristic of masculine hegemony is their steadfastness and reliability; therefore, some may suggest that the masculinisation of social media is the fundamental reason for the censorship of menstruation. The disruptive nature of menstruation, not to mention the hormonal and emotional troubles that accompany it, embody the ways in which this type of social media post cannot portray the desired masculine characteristics. In essence, periods make men uncomfortable as this is not a part of their dominant identity.

Furthermore, Rupi Kaur’s experience with censorship exemplifies women being shut out of a place where they should be allowed to exist freely and post about their own experiences without consequence. Kaur states that “we are not outraged by blood. we see blood all the time. blood is pervasive in movies, television, video games. yet, we are outraged by the fact that one openly discusses bleeding from an area that we try to claim ownership over.” (Lese, 2016; 42). Her defiance highlights the emergence of a new type of Feminist – discovering new forms of oppression and forming a new path away from masculine ideals and towards gender equality in an ever-changing world of online technology.

2.2 Sex Work

A further example of hegemonic masculinity oppressing women through overt censorship is the condemnation of sex workers. Sex work has been a part of society for centuries, usually as a way of making money for those who have nothing else to give but their bodies. In the past, work of this nature has always been regarded as shameful – therefore it must be done in secret so as to prevent sullying the reputation of both the provider and the buyer of the service. Furthermore, it has been said that “the vagina has served as a condensed symbol of all that is secret, shameful and unspoken in our culture.” (Price and Shildrick, 1999; 109). Though it exists to this day, nowadays it is more nuanced; largely due to developments not only in technology itself, but in the manner in which we, as a society, utilise it. Of particular significance is the fact that in modern environments it has become increasingly popular to sell nude images/videos online. The following case study depicts the journey of Lenny Holmes, as she makes large sums of money very quickly through utilising popular pornography subscription website OnlyFans.

Many forms of sex work are typically very dangerous for women – not only are they put at risk of contracting a variety of sexually transmitted infections, they are completely at the mercy of whichever man has paid for their company. Therefore, in this way, the transition of sex work onto the Internet has made this profession much safer for women. Websites such as OnlyFans ensure that the sex worker is granted a platform in which her personal details are protected, she can earn standardised rates and ensure that she is paid correctly. It also means that she does not have to be in physical contact with her clients, which helps to protect her safety while working. In essence, “women’s sense of security in a public space is profoundly shaped by our ability to secure an undisputed right to occupy that space.” (Price and Shildrick, 1999; 363). Websites such as OnlyFans give women a legal, regulated, and therefore undisputed right to occupy their online space, which thereby increases their sense of security.

The issue with this in regard to censorship, is whether or not sex workers should be allowed to promote their OnlyFans (etc.) accounts on social media websites, as is usual for other forms of work. On most social media platforms, the distribution of pornographic content is not allowed. However, on Twitter, the rules are much more relaxed. The two policies surrounding this are: any content displaying nudity must be consensual, and no content may sexually exploit children (The Twitter Rules, 2020; np). Therefore, this provides sex workers with a lot of leeway to promote their services via Twitter.

Lenny Holmes is a 21-year-old woman from Yorkshire with 38,600 Twitter followers (correct as of 14/03/20). In January 2020, after months of struggling to meet financial outgoings and obligations between both her part-time job at Victoria’s Secret and her student loan, Holmes decided to set up an OnlyFans account. Since then she has risen to be within the top 1% of OnlyFans content creators and made upwards of £10,000 within her first week (Holmes, 2020; np). In doing this, Holmes became far more financially stable; comfortably paying all her bills, and buying expensive luxury items. She has also commented that the extra money would assist her in paying off her student loans, and has since resigned from her part-time job as a result of the extra income. However, she has received a large amount of backlash from other Twitter users when promoting her OnlyFans on her existing Twitter platform.

When using Twitter to promote sex work, it is not uncommon for individuals in the adult industry to post images as an example of context which would be found when paying a subscription to OnlyFans. These images are usually not too explicit – an underwear or bikini shot in a provocative pose at the most – and there is rarely full nudity. However, many people feel that content of this nature is still not appropriate to be posted on social media; in come cases being very vocal about the matter. Rude commentaries can frequently be located on these types of advertisement posts, essentially bullying sex workers for being sex workers. One prime example of this was seen when a man told Holmes…

“Imagine having to resort to selling pics or videos of ur body because you have zero talent and don’t see the long term affects of posting intimate videos for yourself online for a few quid to strangers, even more unrealistic standards for girls to believe are normal.” (@RossTea4, 2020, np).

This comment, along with many others, suggests that certain social media users believe sexual content should be censored as it violates what they perceive to be basic standards of self-respect. Other reasons include protecting the innocence of the social media users who are children or other users who lack maturity, as well as that of the many underage people who are being exploited in the porn industry. Some would argue that the porn industry creates a false picture of what sex is, which counteracts the importance of young people learning about sex. The disapproval of the masses can lead to certain posts being removed by social media officials via the system in which users can report a post they believe to be inappropriate. Thus, the fact remains that it is often considered uncouth for a woman to publicly partake in or enjoy her sexuality. (“The young girl may succeed in accepting the fact of her desires, but usually they retain a cast of shame. Her whole body is a source of embarrassment.” (De Beauvoir, 1988; 355)). Therefore, this is an example of hegemonic masculinity as men are thought to be the ones with dominant sexual prowess, not women. So any attempt at reversing this is usually not well received by society. To a large extent, this attitude contributes to the censorship of sex work online. The question can therefore be reduced to a matter of whether this censorship is part of a genuine struggle to protect the population, or is it yet another attempt to render women invisible?

This may be construed as an overreaction – on most social media platforms, after all, there are ways to restrict content that each user may individually find offensive. For instance, it is possible to block another user, and by doing this the individual will no longer see anything the offending person posts, nor be contacted by them. Similarly, Twitter has a function in which a person can mute key words, and thus be unable to see any Tweets containing these words. Facebook even has an option in which, an image or video contains sensitive content, it is covered up, and the individual is warned that the content may be offensive but they can uncover it if they wish. It is also possible to set parental restrictions on most websites. Within an online world that is so open to individual censorship, it seems unreasonable for users to wish to remove sexual content as a whole – when they can simply choose not to see it.

The porn industry as a whole tends to revolve around men. When the concept of “cyber-sex” came about, there were multiple “sex games” which people could buy; but none (as pointed out by Price and Shildrick, 1999; 141) of these seemed to be “produced by or for women.” In this day and age, women are empowered to create their own sexual content, but there is still very little of this which is intended for female enjoyment. Usually, the idea is to utilise the male gaze and appeal to it. This way of making money suggests that the industry is controlled by patriarchal forces, despite its guise of female empowerment. At a glance, the majority of criticism that Holmes received seemed to be directed towards whether or not her father would approve of her behaviour. Therefore, men appear to always be reducible to the root of a sex worker’s motives in one way or another. Although it could be argued that by working in this industry the sex worker’s job is to open herself up to scrutiny, it is impossible to avoid criticism, no matter how demoralising. Of significance here is a quote from Foucault (1977; 155) which surmises scrutiny, in that it can be applied to the male gaze with ease: “there is no need for arms, physical violence, material constraints. Just a gaze. An inspecting gaze, a gaze which each individual under his own weight will end by interiorising to the point that he is his own overseer.” (Price and Shildrick, 1999; 253). The language used to describe Holmes’ work is often very degrading, and this lack of respect is a prime example of how sex work has historically been regarded as dirty or shameful. This is highlighted by the way that most social media platforms will not allow sexual content; the subject of sex work has always been, and evidently remains, taboo.

Overall, a Feminist would argue that sex work should absolutely be allowed to filter into social media. Many people use their social media accounts for work, and this should not be any different for those in the porn industry. To censor this is to diminish women’s ownership of their own bodies and to encourage the taboo against sex work. Why censor the human body when we all have one? Ultimately, the censorship of sex work promotes attitudes of hegemonic masculinity as it furthers the age old idea that women must be sexually attractive and submissive to please men, but that this must not be public. “This humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as a relative to him; she is not regarded as an autonomous being.” (De Beauvoir, 1988; 16). It is also worth noting that there are also male sex workers who face these issues, but that this is far less common.

3 Covert Censorhsip

3.1 Fatphobia

Whilst – as discussed in the previous chapter – certain women’s issues are very overtly renounced from society, it is important to consider those which are just as invisible, but often more subtle. The removal of larger women from the media is one such issue. Women’s media (fashion magazines, clothes shops and websites, etc.) has for many years promoted an ideal body type for women. The unattainable size-zero-Barbie-body has always been a driving consumerist force which has propelled women down the route of diet plans and weight loss products. However, the rising popularity of social media has brought into the light whole new groups of oppressed women. The issue of which women? arises here, in which it becomes clear that female oppression relates to much more than the oppression of females as a whole; rather distinctive subcategories may find themselves subject to heightened oppressive forces – with the notable example of this section concerning those of a heavier disposition. Women of differing body types will see vastly different representations of themselves on social media, and this can be very damaging to an individual’s mentality surrounding their own self-image. What is particularly notable about this type of censorship, however, is that women who may be considered fat (i.e. larger than a UK size 14) have not been banned or prohibited by rule or regulation; they have simply not been included in the first place. The Instagram-based influencer, Megan Crabbe, works as an advocate for the body positivity movement, and the community she has created perfectly demonstrates an ethos of self-love and self-acceptance, no matter a person’s size.

Crabbe’s mission is to overturn negative perceptions of “fatness” through documenting her own journey – from overcoming anorexia as a teenager to the current day in which she embraces her own body (despite it being too large to be deemed healthy by most). She states: “Even the 5% who fit societal standards of beauty fall short against the work of a photoshop wand, erasing every lump, bump, crease, mark, scar, blemish and hair. How can we believe that our bodies are worth something when we never see them positively represented around us?” Her online following currently stands at approximately 1.3 million (Instagram, correct as of 16/03/20), therefore it can be acknowledged that her message of self-acceptance is fairly widespread. Many of her followers claim that she has helped them to overcome eating disorders, whilst others claim she has helped bolster their self-confidence. However big or minor the impact on each individual, Crabbe’s influence has proven to be undeniably positive on a wide scale. The community aims to bring larger women into the light, and show that they are just as strong, successful and beautiful as their thinner counterparts. Marilyn Wann, author of FAT!SO? recommends that anyone struggling to use the word fat in a way that is not negative should: “practice saying the word fat until it is the same as short, tall, thin, young, or old.” (Farrell, 2011; 137). For Wann, the way to end fat shame is to “lose the stigma, not the fat,” thus removing the blame from the victim and placing it onto society. Crabbe takes lots of her ideals from the singer Lizzo, who is unapologetically fat whilst being very successful and prominent in the public eye – which can be acknowledged as an impressive feat given prevailing attitudes among various members of our general physical and digital communities.

Negative perceptions of “fatness” have transpired not only into women’s everyday lives, but into motherhood, via the morality of having overweight children. “Statements disguised as concern are spewed from the lips of others who were not asked their opinions, but they chose to give them away anyway because mothers and keepers of fat bodies are viewed as being in constant need of public opinion for their own sake and the sake of their children.” (Verseghy, 2018; 185). This sense of superiority that thin people seem to have over fat people perpetuates the stigma against fatness and confirms that fat people are simply not welcome in society.

An issue which Crabbe feels strongly about is the media’s apparent obsession with diet culture. Defined here by Christy Harrison (2018: np), diet culture revolves around a system of beliefs that “worships thinness and equates it to health and moral virtue… [that] promotes weight loss as a means of attaining higher status… [and] demonizes certain ways of eating while elevating others… [it] oppresses people who don’t match up with its supposed picture of “health.” In other words, it can be very damaging to those who are insecure about their bodies; making them feel as though they are unfit to belong in society and that they have to change to reach the unattainable standards set by the many supermodels and celebrities who adorn our high streets and dominate the media, actively promoting this way of thinking. An example of this was shown in a semi-recent news story, in which Kim Kardashian was criticised for advertising an appetite-suppressing lollipop (produced by the somewhat aptly named Flat Tummy company). Immediately, Kardashian received large amounts of backlash, for example Jameela Jamil (2018; np) took to Twitter, calling Kardashian a “terrible and toxic influence on young girls.”

This condemnation of women’s natural bodies stems from a centuries-old idea that women must look their best in order to find a husband/mate. This incessant desire to please men has lessened over the years as Feminism has grown, however the attitude of self-improvement is still very important to many women. As shown in a comment from Price and Shildrick (1999; 347); “via anorexia, slimming, cosmetic surgery, the fashion industry and simply the way they stand, move or play, women discipline their body boundaries intensively.” There is constant pressure from the celebrities of social media, who edit their photographs to make themselves appear thinner, curvier, bustier, with slimmer faces and perfect make up and no blemishes. The ordinary woman, however, does not see this editing process; she is led to believe that these women are simply extraordinarily beautiful. This, in itself, promotes feelings of inferiority. Overall, then, it is clear that online media is not a place which welcomes plus size women.

Megan Crabbe attempts to overturn this idea by promoting other fat influencers, and by taking all opportunities she can to put herself and other large ladies into mainstream media – meanwhile not excluding any other body type, her community is one of inclusivity for all. She has done multiple photo shoots (including nude ones) with photographer Linda Blacker, to show that fat bodies can be beautiful too. Crabbe has also featured on the cover of several magazines, such as Happiful, thus helping fatness become more normalised in traditional media. She hopes that this proves to her audience that they are capable of doing anything because their size does not determine their worth. The use of nude photo shoots contradicts the Instagram guidelines in their statement: “nudity is not permitted.” (Instagram, 2020; np). In previous years (now removed due to criticism), the guidelines expressed this by using the phrase “keep your clothes on.” As Olzanowski (2014; np) points out, this phrase is embedded with moral superiority – “a dismissal of nudity with the assumption that either you are a person who should keep their clothes on (often used for fat – or trans – shaming) or that showing your body is intolerable and inappropriate in whatever context the phrase is uttered.” This is yet another way in which women’s bodies are rejected from the media because they are not appealing to men. Modesty can therefore be said to be one of the traditional characteristics of a woman, which promotes hegemonic masculinity through encouraging female subordination.

Some may also say that to be fat is to be less feminine or attractive – for example in film and television “fat women are less likely to be portrayed as being the object of romantic interest.” (Fikkan and Rothblum, 2011; 585). This is largely due to the previously discussed notion of femininity equating to thinness. Crabbe turns this idea on its head by demonstrating the vast dichotomy between ideals of the modest, classy, “traditional” conception of femininity – through openly challenging these norms without appearing any less feminine. She is somewhat burlesque in her portrayal of femininity, wearing outlandish and sometimes risqué outfits which many would not consider appropriate for a woman her size. A quote by Simone De Beauvoir encapsulates the dynamic that Crabbe is overturning: “to be feminine is to appear weak, futile, docile. The young girl is supposed not only to deck herself out, to make herself ready, but also to repress her spontaneity and replace it with the studied grace and charm taught by her elders. Any self-assertion will diminish her femininity and her attractiveness.” (De Beauvoir, 1988; 359). Crabbe does not repress her spontaneity or attempt to blend in in any way. She looks beautiful in her own unique way, and does this for herself, not for any man. She is totally and unapologetically bizarre, with confidence, and entertaining no regard for the thoughts her critics (who, perhaps not surprisingly, are usually men).

3.2 LQBTQ+ Identities

Over recent decades, the LGBTQ+ community has flourished. Since the legislation of homosexuality in 1967, the community has fought for increasing the visibility of anyone falling within the remit of this category. In the present day it is now legally and morally wrong to discriminate against someone with regard to their sexuality and/or transgender status, as can be seen through the introduction and gradual expansion of legislative mechanisms like the Equality Act 2010. The way in which queer people are viewed in society has rapidly altered, and a large part of this can be attributed to a rise in social media usage. Social media and globalisation have helped to bring communities of people together; with the rise of the LGBTQ+ community being a prime example.

Sexuality can be considered a Feminist issue because the reality of being a lesbian or bisexual woman is very different from the reality of being a gay man. Gay people are, as a general rule, more widely accepted for their sexual identity, whereas for a woman, being homosexual is more likely to be considered a “phase” or a ploy for attention. For example, homosexual women are often told they just haven’t found the right man yet or vice versa. Therefore, it may be argued that debates concerning the very existence of lesbians alter their experiences when in both the physical and the online world. This potentially relates the idea of biological determinism, wherein the woman is expected to submit to her husband and cook/clean/bear children simply because that is what her gender predisposes (Price and Shildrick, 1999; 42-43). The idea of being a lesbian has connotations of female independence from or even total renunciation of men – which is not considered stereotypically feminine – and therefore does not fit the societal norm of hegemonic masculinity. Thus, female homosexuality is practically non-existent in the minds of many who succumb to these ideals. Even less is the idea that a woman can be a lesbian and still be feminine. For example, Price and Shildrick (1999; 112) comment that the idea of a stereotypical masculine lesbian body has always existed, and many feel that “the lesbian really is a man trapped in a woman’s body.” This could be said to be the idea which began the stereotype of the butch lesbian.

Whilst homosexuality or other LGBTQ+ identities in themselves not censored by way of being expressly banned or prohibited, it is still very much hidden from the online world in several ways. There are still vast groups of people who do not agree with homosexuality, and spread hateful comments and posts on social media. Such is frowned upon by most online communities, and often this type of hateful message will be “flagged” by other users and removed from the platform/site by officiators – but much still trickles through. And although it can prove very harmful to the groups it targets, the people who make hateful comments usually view them as falling within their right to freedom of expression and opinion. For example, Kat Matson is a 20 year old Twitter user who has “come out” as transgender in the past year. The recent period of transition has been difficult for her and she has struggled with her confidence. With the support of her family and friends, in 2019 she made a Tinder account in order to try to form a romantic attachment with someone who she could find attractive truthfully within her new identity. However, one Tinder user reported Matson’s account as being inappropriate when they found out that she is transgender. This led to Tinder deleting Matson’s account on the website without looking into the matter further. Although this appears to be an isolated incident, this exclusion is the lived experience of many LGBTQ+ individuals in the modern day. An article from Business Insider (2015; np) goes into further detail: “Tinder relies on gender to sort users and offers two options — male and female. A user selects their own gender, and then selects which genders they would like to be matched with — male, female, or both. Because of this, transgender people have no way of filtering out people who don’t want to match with them. This is what leads to the erroneous reporting.” The controversy these attitudes have caused sometimes makes it difficult for larger companies to be inclusive of LGBTQ+ people for fear of losing customers or receiving backlash. This is an example of covert censorship whereby exclusion does not occur by any positive acts or intentions of the excluding parties, yet failure of inclusion occurs nevertheless through creation of an environment in which groups feel they do not belong. Ergo, there is very little written evidence of transgender people being censored, but it can be seen in the straight, cisgender portrayal of many mainstream media websites.

Although the debate over fitting into society has been a very long-standing issue, more recently, issues around transgender have become increasingly prominent. Whilst gender has always been a source of enquiry for traditional Feminist sociologists, few have looked into gender in any manner more significant or meaningful than directly comparing men to women. Oakley (1972; 149-165) looked at case studies of hermaphroditic individuals and concluded that it is possible to have both female chromosomes and male genitals and vice versa, as well as genitals that have not developed. However these patients each had their own gender identity based on how they had been raised, therefore gender is a social construct. Her work is very relevant today with the rise of transgender identities, as it gives us insight into the history of being transgender and how society’s perceptions on the matter have altered. For example, on mainstream media advertisements for clothing companies, it is very rare to see a model whose gender is not obvious, or androgynous.

In the present day, negative attitudes towards transgender people have manifested online. Some social media platforms such as You Tube have been accused of being anti-LGBTQ+ as their restricted mode (intended to create an appropriate viewing environment for families) removed most videos which included LGBTQ+ content due to it being considered inappropriate. For example, one You Tube user had all of her videos which made reference to her girlfriend taken down, but none of those which referenced a boyfriend. You Tuber Rowan Ellis made a very poignant video about this, stating: “underneath the surface, we know that this is about the sexualisation of trans people! The idea that trans and queer people are inherently sexual and perverse in their sexuality … [this attitude is] inciting ignorance into a new generation.” (Ellis, 2017, np).

Homosexual and transgender people usually do not neatly fit into the masculine stereotype. This is because they are often more effeminate, and may lack such physical attributes of the traditional “male” such as a deep voice and facial hair. This idea of being unable to fit into society’s gender ideals can lead to a person dressing and behaving in a certain way in order to fit in with what their gender is supposed to look like. This is a manifestation of Goffman’s dramaturgical approach, in which he suggests that a person never shows their true self to others, they simple act in accordance to their surroundings as though they are actors on a stage. “When an individual appears in the presence of others, there will usually be some reason for him to mobilize his activity so that it will convey an impression to others that it is in his interests to convey.” (Goffman, 1959; 16). In this, there is the suggestion that the idea of maleness or femaleness is very much a social construct and that people feel they are required to act as one or the other – which effectively excludes transgender people from mainstream society.

By extension, it could be argued that drag acts have developed into a way of normalising this culture of androgynity. Price and Shildrick (1999; 418) argue that “by imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself – as well as its contingency.” This furthers the idea that gender is performance-based, as drag shows gender performativity in its most obvious form (in an almost parodical sense). Although drag has been around for years (Danny La Rue for example), it is steadily becoming more widely accepted in society (through TV shows such as Ru Paul’s Drag Race), and by increased exposure to social media, it would be almost unheard of for a large media-based company to promote this (e.g. by using models who are dressing in drag). This is because no matter how popular drag gets, it is still never going to be taken with the same manner of acceptance by a society that continues to embody the hegemonic masculine ideals that have been ingrained into people for years, if not centuries.

4 Results and Methods

The aim of this study was to address the idea of hegemonic masculinity being a prominent influence into patriarchal censorship on social media. The most appropriate method of investigating this appeared to be using questionnaires to assess public opinion on censorship, and then to compare the results by gender. This also meant that in terms of ethics there were only a few minor things to consider, such as participants’ age, and how distressing they may find the questions. Therefore, it was made clear to respondents that they must be over the age of 18 and that they had a right to withdraw from the study at any time. To ensure that the research was valid it was necessary to write the questions in a way that people with no sociological knowledge would understand. It was also important to make sure the same questionnaire was sent out to each person with no editing, which made the research more standardised.

When designing the questionnaire, it was necessary to base the questions on the issues which would later be discussed in the essay. The ten questions used were designed in various styles in an attempt to prevent boredom and to keep the respondents interested. These consisted of three multiple choice questions, three multiple answer questions, one image based question and three open-ended questions. In doing this, the respondents would ideally complete the questionnaire in full because they would not be bored of answering similar styles of question. Participants were mostly recruited via Facebook, because it made sense that people who use social media would have a better understanding of online censorship than those who do not. This involved sharing the questionnaire via personal Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts, ergo among family and friends. The idea behind this was that the questionnaire would then be shared through word-of-mouth as well as online; thus, achieving a more varied response rate whilst maintaining a focus group of social media users. Another way that is was shared involved a closed Facebook group called “Dissertation Survey Exchange.” This is a group of students from around the world who each share their dissertation questionnaires in the hope that people will complete them. This is usually done by an exchange – i.e. a person will share their questionnaire and offer to complete another’s questionnaire in exchange for that person completing theirs.

The questionnaire itself was put together on Survey Monkey because it is clearly designed and easy to use on both computer and mobile devices. The link to the questionnaire was open from 2nd December 2019 to 17th February 2020, as this provided ample time for respondents to see the link that was shared on their social media, and to come back to it if they wished. The questionnaire took respondents an average of five minutes and thirty-three seconds to complete. All in all, 100 responses were collected. This became the cut-off point as it was a simple number to work with, and by this point the questionnaire had been live for a reasonably long time, therefore it was unlikely to gather many more responses if left longer.

4.1 Quantitative Data

The questionnaire provided both quantitative and qualitative data. To analyse the quantitative data, it was important to check it before analysing, in case of any outliers or missing data. To do this, it was most appropriate to go through each response, uploading it manually onto SPSS. This meant that it was possible to see each person’s response to each question, making it easier to check for outliers or missing data (there were none). This was more time consuming, but made the data screening more thorough. From the data collected it was clear that the most useful form of analysis would be Crosstabulation with Chi-square testing. This is because none of the data was continuous (i.e. gave a numerical or scale answer), therefore no detailed analysis such as ANOVA or even t-tests could be conducted and bivariate analysis had to be used instead. Crosstabulation was the correct method of analysis to use as the underlying assumptions of this type of non-parametric test matched the data. For example, the data must be nominal or ordinal, the sample group sizes must be unequal and the categories must be mutually exclusive. With the analyses, the independent variable is gender and the dependent variable is the other which will be compared to gender.

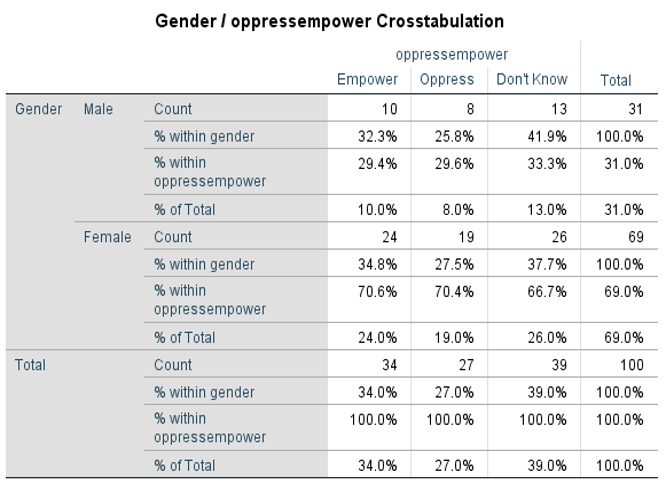

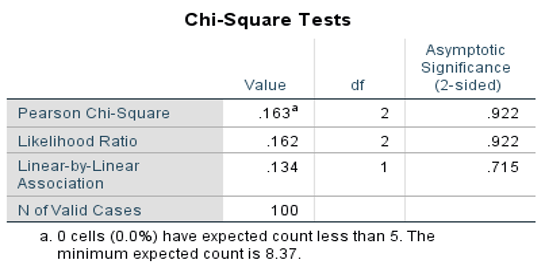

The first set of data shown here depicts the association between the respondents’ gender, and their opinions on whether posting nude images is oppressive or empowering for women. The alternative hypothesis is that there is a significant relationship between the variables “gender” and “oppressempower.” The null hypothesis is that there is no significant relationship between these variables, and any relationship shown is due to chance.

As shown in fig. 1, there is a clear imbalance of male and female respondents. However, the Crosstabulation table allows a way of seeing the various responses within each gender. There is not a huge amount of difference between male and female responses, although for each gender the highest percentage responded that they didn’t know whether posting nude images would oppress or empower a woman (39% of total). This could be an indication of the question being worded poorly or being too simplistic. Within those who chose a side, the empower side won out with both genders – 32.3% of males and 34.8% of females (within gender) voted for this, compared to the slightly lower 25.8% (male) and 27.5% (female) who voted for oppress.

However, this information only gives a descriptive insight so thus far it is not possible to tell whether there is a significant difference between “gender” and “opressempower.” This can be determined through a Chi-square test, shown in fig. 2. From this it can be said that there is not enough evidence to determine a significant relationship between “gender” and “oppressempower,” as the p value of 0.922 is higher than the significance level of 0.05, and therefore the null hypothesis must be accepted. This could be because there are a higher number of females than males in the sample, or simply that the sample size is just too small.

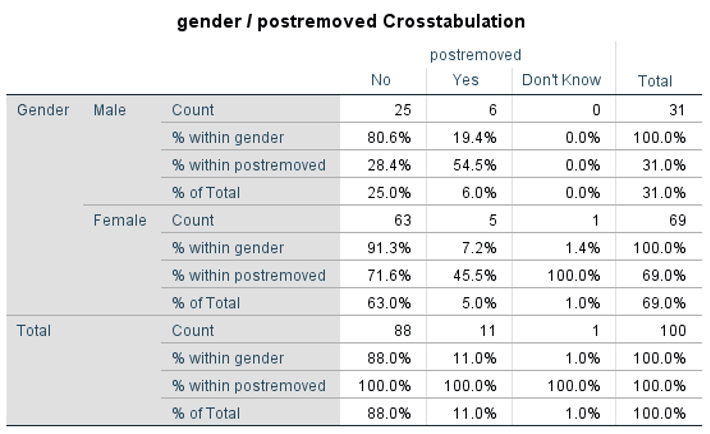

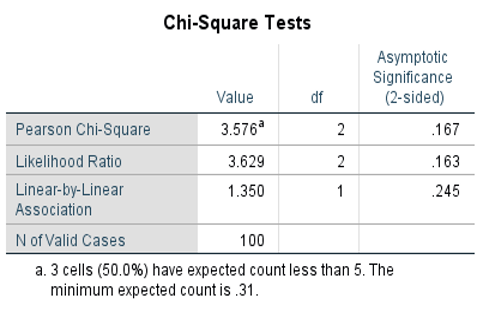

The second set of data shows a Crosstabulation table of the variables “postremoved” and “gender.” This is to determine whether participants have ever had one of their posts taken down from social media. Similarly, the alternative hypothesis is that there is a significant relationship between participants’ gender and whether they have ever had a social media post removed. The null hypothesis is that there is no significant relationship between these variables and any relationship shown is due to chance.

Fig. 3 shows that the majority of respondents (88% of total) had never had a post removed from social media. Of those who had, there was somewhat of a gender difference, with 19.4% of males and 7.2% of females having had a social media post removed. This is immediately surprising as the idea behind this research was that females would have had more posts removed due to patriarchal censorship. On the other hand, it could prove that females have been forced to become more self-policing in terms of the kind of content they post, whereas males are less likely to consider the implications.

However, it is still unclear as to whether this difference is significant until further analysis is performed, as Crosstabulation tables only allow description of the data. Shown here in fig. 4, the p value of 0.167 means it can be determined that the data is not significant and therefore the null hypothesis must be accepted – there is no significant relationship between “gender” and “postremoved.”

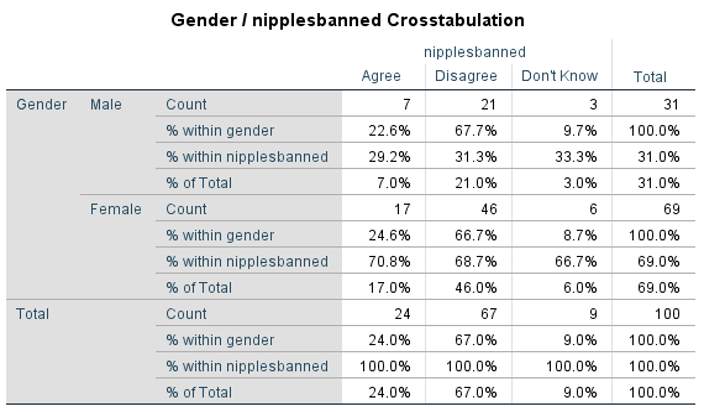

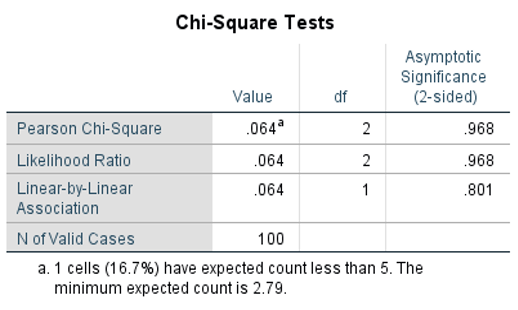

The third set of data will assess the relationship between participants’ gender and their stance on whether the female nipple should be censored online. Again, using Crosstabulation tables, the alternative hypothesis is that there is a significant relationship between “gender” and “nipplesbanned.” The alternative hypothesis is that there is no significant relationship between these variables and any association is due to chance.

As shown in fig. 5, there is no obvious gender difference between those who agree with the censorship, and those who disagree or don’t know. For example, 67.7% of males disagree (i.e. think that nipples should not be censored) compared to 66.7% of females. These numbers are extremely close together, so it is unlikely that there will be a significant association between the two. This can be assessed, as with the prior tests, through a Chi-square test.

Shown here in fig. 6, these assumptions are confirmed. The p value of 0.968 is higher than the significance value of 0.05, so any relationship is insignificant. Therefore, the null hypotheses must again be accepted. This is surprising as the issue of male vs. female breast tissue has been an obvious double standard in society for decades (i.e. it is deemed acceptable for a man to be fully topless in public but not for a woman). Therefore, one might assume that women are more aware of this issue and be more likely to disagree with the censorship than men. Alternatively, it could be interpreted that the equality of response could be due to a rise of male feminism, or their perceived sexualisation of the female breast.

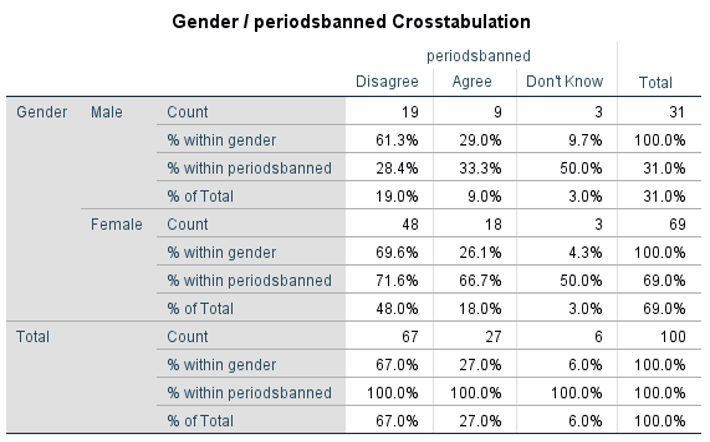

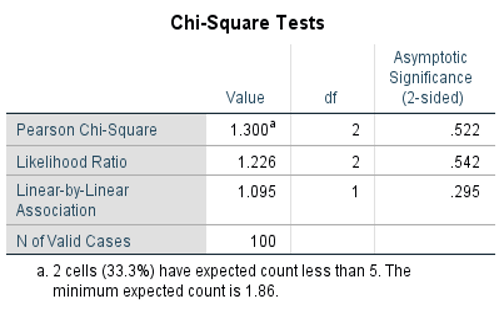

The fourth observation will consider the relationship between participants’ gender and their stance on whether images of menstruation should be censored online. The alternative hypothesis is that “gender” will have a significant relationship with “periodsbanned.” The null hypothesis is that there is no significant relationship between these variables, and any relationship shown is due to chance.

Fig. 7 shows the Crosstabulation table of these variables. It indicates that there is a wider gender difference than in previous comparisons, but still overall very small. For example, 61.3% of males disagree with menstrual censorship, compared to 69.6% of females.

Again, this is only descriptive information, so a Chi-square test is necessary to ascertain the significance of the data. Shown here in fig. 8, it transpires that this data is not significant, as the p value of 0.522 is higher than the significance value of 0.05. Therefore there is insufficient evidence to say that gender has any opinion on attitude towards menstrual censorship, thus the null hypothesis must be accepted. This could be due to a rise in Feminist attitudes in men, or the data could have been skewed due to the fact that there were far fewer male respondents than female respondents.

Overall, then, the data collected here was not successful in proving the hypotheses. A p value of 0.05 or less would have meant that there was a 95% chance that the relationship was significant. None of the p values shown here even came close to this number, so it is clear that the data was quite insignificant. Crosstabulation tests only cover simple bivariate analysis, so it is possible that more may have been discovered if more stringent levels of analysis had been used. However, this particular data set did not contain any continuous data, which therefore ruled out analysis such as the t-test or ANOVA, because they require more complex data than tests only cover simple bivariate analysis, so it is possible that more may have been discovered if more stringent levels of analysis had been used. However, this particular data set did not contain any continuous data, which therefore ruled out analysis such as the t-test or ANOVA, because they require more complex data than agree, disagree, or don’t know, which is what was used here. This could have been avoided if the questionnaire had been more thoughtfully designed – the addition of Likert-scale questions for example would have drastically changed the usability of the data. In addition to this, a sample size of 100 is relatively small, and tests such as ANOVA require much larger samples in order to be effective.

4.2 Qualitative Data

As for the qualitative data – open-ended questions were used three times in the questionnaire. The first one was demographic; by allowing respondents to write their own gender it felt less constricting than to make them choose a tick box from a category they may not fit into. The second was “On Instagram, posting images of female nipples is banned, but posting images of male nipples is not. Do you feel that this double standard is reasonable? Why?” This question provoked various responses, falling into what appears to be three main categories: agree, disagree, and don’t know/depends on context. These categories were then coded and analysed quantitatively, as shown above. The largest group of respondents (67% approx.) argued that they disagree with the censorship of female nipples. Shown here are some of the more compelling reasons given in this category:

“No. I don’t feel like this is reasonable … I feel that Instagram are sexualising female nipples but not males and therefore deeming them as inappropriate content. This tells women that they must cover their bodies when men should not.”

“No. The nipple can be used for sexual arousal in men and women, but for some reason women’s breasts are sexualised and men’s nipples are not.”

“All should be banned if any.”

“Censorship is what MAKES it sexualised.”

“Insta[gram] are simply upholding patriarchal control of female bodies.”

“A nipple is a nipple.”

The next largest group of respondents (19%) argued that they agree with the censorship of female nipples. Shown here are some of their most compelling responses:

“Not a double standard.”

“A business needs to appeal to the majority of society. The majority (rightly or wrongly) believe that male nipple is ok, whilst female is not. When societal beliefs change, as should the rules on social media.”

“I don’t think it should be acceptable for women because it is private parts of their body and not for men.”

The smallest portion of respondents (13%) stated either that they did not have an opinion, or that their opinion would depend on context. Shown here are some of their responses:

“To some extent, if it is an overly sexualised photo then it’s not okay, whereas if it’s bending [norms] and liberating [women] there shouldn’t be a difference.”

“I believe it’s double standards but I think it protects women from harassment.”

“I think that it’s reasonable because of the way female nipples are oversexualised, however I disagree with them being oversexualised.”

“It’s their choice … but it would be like free porn for most blokes.”

The second open-ended question used in the questionnaire was: “In today’s society, many people feel uncomfortable talking about periods. This has led to lack of education about the menstrual cycle, and a taboo topic. Do you feel that these period-related images are appropriate for posting to social media? Explain your answer.” The images to which the question refers were taken from Rupi Kaur’s Period photo series discussed in chapter 1. The responses were subsequently coded into categories: agree (i.e. with the ban, this is not appropriate), disagree (with the ban, this is appropriate), or don’t know/depends on context. The split was less extreme for this question, but not by much. Most people (61% approx.) argued that they felt that the images were appropriate. Shown here are some of their most compelling arguments:

“It helps to educate more people on the menstrual cycle.”

“Anyone who is made to feel uncomfortable by these images can choose to unfollow or block the content.”

“I feel these images are appropriate, they depict natural experiences which almost all women can relate to, and give an unromanticised image of what periods entail, and becoming familiar with images such as these may help ‘normalise’ the subject of periods.”

“It is empowering to see these images because it shows we do not have to hide.”

“Health education is critical for people, including children, to know when things are normal and when they need help.”

“Many young people seek answers through social media.”

The second largest group were those who argued that the images were inappropriate (27% approx.). Shown here are some of their most compelling responses:

“There are other ways to educate people. Everyone’s experiences are different and these images generalise.”

“No because it is private.”

“Lots of people find it gross and disturbing seeing pictures of blood, particularly other people’s blood.”

“Periods should be talked about more but I think the photos are a bit too graphic or unnecessary for the conversation to be had.”

“As a female these images are relatable but I wouldn’t appreciate seeing them on my social media feed. I’m comfortable with seeing my own but possibly not others’.”

“No, it makes me cringe.”

The smallest group of respondents (12% approx.) voted that the appropriateness of the images would depend entirely on context. Shown here are some of their responses:

“Period awareness yes! As a general post perhaps not, too personal if taken of yourself.”

“Depends on the intention of the person posting them. Many people may do this to be outrageous or make people uncomfortable.”

“As long as they’re educational or informative and not attacking any individual or group.”

Moreover, the qualitative data shown suggests that this type of question is not so clear cut as agree or disagree. There are many different reasons for each which could be covered, so for any future projects it may be pertinent to explore one of these issues in detail, rather than multiple issues broadly. It was necessary to split the data into categories in order to code them to provide data which could be analysed, but this also meant that several of the other survey questions could not be used as they did not provide data that visibly showed anything of interest, or could be analysed. The fruitlessness here lies solely in the question design – they were simply too broad, and did not produce continuous data. The questions were probably too subjective. It could also be said that the open-ended questions were unclear in the use of agree or disagree without providing a clear statement for respondents to react to. Therefore, the conclusion can be drawn that based on this data, censorship in social media does not promote attitudes of hegemonic masculinity.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the aim of this study was to demonstrate that censorship within social media promotes attitudes of hegemonic masculinity. From the literature review, it is made clear that this issue does exist, and that it has adversely affected various groups of people as a whole and as individuals. The written evidence and the case studies used undeniably prove this. The primary research section was intended to back up the literature review, in proving that males would be more likely to agree with patriarchal censorship, and women more likely to disagree with it. However the results were far more evenly split, showing very little gender difference at all, and that, actually, most people disagreed with this censorship regardless of gender.

A nuanced idea which could further develop this research is that censorship occurs even when a woman is fitting perfectly into the stereotypical idea of femininity which society’s hegemonic masculine ideals would deem acceptable. For example, the emergence of Mommy Bloggers has revealed a new type of content creator whose entire online presence revolves around their children, home and lifestyle. One such person is YouTuber and mother of two, Louise Pentland. Her homey videos on motherhood and lifestyle have opened up herself and her children to a world of strong public opinion. Pentland has been criticised by her viewers for things as trivial as her house being messy, employing a nanny, and feeding her baby formula milk. Therefore, the idea of hegemonic masculinity being the driving force behind social media censorship is too simplistic, as it is clear that there are more variables at work.

Moreover, it can be concluded that whilst censorship on social media does promote attitudes of hegemonic masculinity, there are other factors which are both affecting and effects of censorship.

Bibliography

@RossTea4 (2020), Twitter post, np. [Accessed 01/02/20 10:24].

Carfolla, (2015), in Lese, K. (2016), Padded assumptions: A critical discourse analysis of patriarchal menstruation discourse, Masters Theses, James Madison University, Pages 42 and 52.

Clement, J. (2019), Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 3rd quarter 2019, Statista Statistics, np. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ [accessed 06/01/20 14:58].

Crabbe, M. (2017), @bodyposipanda Instagram page, np. [Accessed 16/03/20 18:15].

De Beauvoir, S. (1988), The Second Sex, Picador Classics Edition, London: Pan Books Ltd, Pages 16 and 355.

De Beauvoir, S. (1988), The Second Sex, Picador Classics Edition, London: Pan Books Ltd, Page 359.

Donaldson, M. (1993), What is Hegemonic Masculinity? Australia: University of Wollongong, np.

Eisenberg and Micklow (1974), in Reinharz, S. (1992), Feminist Methods in Social Research, New York: Oxford University Press, Page 82.

Ellis, R. (2017), YouTube is Anti – LGBT? (Restricted Content Mode), Rowan Ellis via YouTube, np. https://www.youtube.com/embed/Zr6pS07mbJc [accessed 17/03/20 12:36].

Farrell, A. (2011), Fat Shame: Stigma and the Fat Body in American Culture, NYU Press, Page 137.

Fikkan, J and Rothblum, E. (2011), Is Fat a Feminist Issue? Exploring the Gendered Nature of Weight Bias, Feminist Forum, Page 585.

Goffman, E. (1959), The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, London: Penguin Books Edition, Page 16.

Google Dictionary definitions of Overt and Covert. [Accessed 19/03/20 11:59].

Harrison, C. (2018), What is Diet Culture? Blog post at www.christyharrison.com, np. [Accessed 04/02/20 10:47].

Hekman, S. (1999), The Future of Differences: Truth and Method in Feminist Theory, Cambridge: Polity Press, Page 84.

Holmes, L. (2020), @lennholmes Twitter page, np. [Accessed 14/03/20 14:37].

Instagram Community Guidelines (2020), https://help.instagram.com/477434105621119/?helpref=hc_fnav&bc[0]=Instagram%20Help&bc[1]=Privacy%20and%20Safety%20Center [Accessed 14/03/20 14:19].

Instagram. (2020), Community Guidelines, np. https://help.instagram.com/477434105621119 [Accessed 04/02/20 18:38].

Jamil, J. (2018), @jameelajamil on Twitter, np. https://twitter.com/jameelajamil/status/996603187623641090?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E996603187623641090&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.huffpost.com%2Fentry%2Fkim-kardashian-appetite-suppressant-lollipops_n_5afc1262e4b0a59b4dff3d3f [accessed 04/02/20 11:05].

Kaur, R. (2015), Instagram post by @rupikaur_. [Accessed 07/01/20 12:17].

Kaur, R. (2017), www.rupikaur.com “about” page. [Accessed 07/01/20 12:08].

Kircher, M. (2015), Transgender People are Reportedly Being Banned from Tinder, Business Insider, np. https://www.businessinsider.com/transgender-tinder-users-reported-and-banned-2015-6?r=US&IR=T [Accessed 17/03/20 14:36].

Oakley, A. (1972), Sex, Gender and Society, Bath: Pitman Press, Pages 158 and 179.

Olzanowski, M. (2014), Feminist Self-Imaging and Instagram: Tactics of Circumventing Sensorship, Visual Communication Quarterly, Vol 21; 2, Pages 83-95.

Price, J. and Shildrick, M. (1999), Feminist Theory and the Body: a Reader, Edinburgh University Press, Page 12.

Price, J. and Shildrick, M. (1999), Feminist Theory and the Body: a Reader, Edinburgh University Press, Page 2.

Price, J. and Shildrick, M. (1999), Feminist Theory and the Body: a Reader, Edinburgh University Press, Pages: 109, 141, 253 and 363.

Price, J. and Shildrick, M. (1999), Feminist Theory and the Body: a Reader, Edinburgh University Press, Page 347.

Price, J. and Shildrick, M. (1999), Feminist Theory and the Body: a Reader, Edinburgh University Press, Pages 42-43, 112 and 418.

Twitter. (2019), Terrorism and Violent Extremism Policy, Twitter Help Centre, np. https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/violent-groups [Accessed 06/01/20 15:14].

Twitter. (2020), The Twitter Rules, Twitter Help Center, np. [Accessed 30/01/20 14:30].

Verseghy, J. (2018), Heavy Burdens: Stories of Motherhood and Fatness, Bradford: Demeter Press, Page 185.